On the afternoon of the winter solstice that’s just passed, as I was about to enter the Natsume Sōseki Memorial Museum, a group of elderly Japanese men arrived. One of them carried a flag with “Sharp” on it; it was a friendship group made up of former employees of the company that made my vacuum cleaner, TV, and oven—and, years ago, my first sound system, which I used to explore the classical repertoire for the first time. The group, entirely male, took a keen interest in the exhibits of the museum.

Looking into the company’s history later, I glimpsed unexpected parallels between the lives of the founder of Sharp, Tokuji Hayakawa, and the novelist Sōseki. Both were adopted (Sōseki for about ten years) and suffered miserably at the hands of their adoptive parents. Hayakawa, a classic self-made inventor and then industrialist, went on to develop the famous Ever Ready Sharp mechanical pencils. So in a sense, both he and Sōseki were in the writing business. More importantly, both were shaped by—and also helped to shape—the Meiji era (1868–1912), the age of Japan’s great period of modernisation.

The novelist Natsume Sōseki (1867–1916) is unquestionably one of the giants of modern Japanese literature, and given the period he was born into, it’s not surprising that one of the key themes in his writing was the rapid Westernisation and industrialisation of Japan. Japanese schoolchildren read from his 1914 novel Kokoro (“Heart”) at high school. He was born in the same year as John Galsworthy, he was also a rough contemporary of Ford Madox Ford and Joseph Conrad. But somehow the European writer he most remains me of (at least in Kokoro) is Miguel de Unamuno (1864–1936).

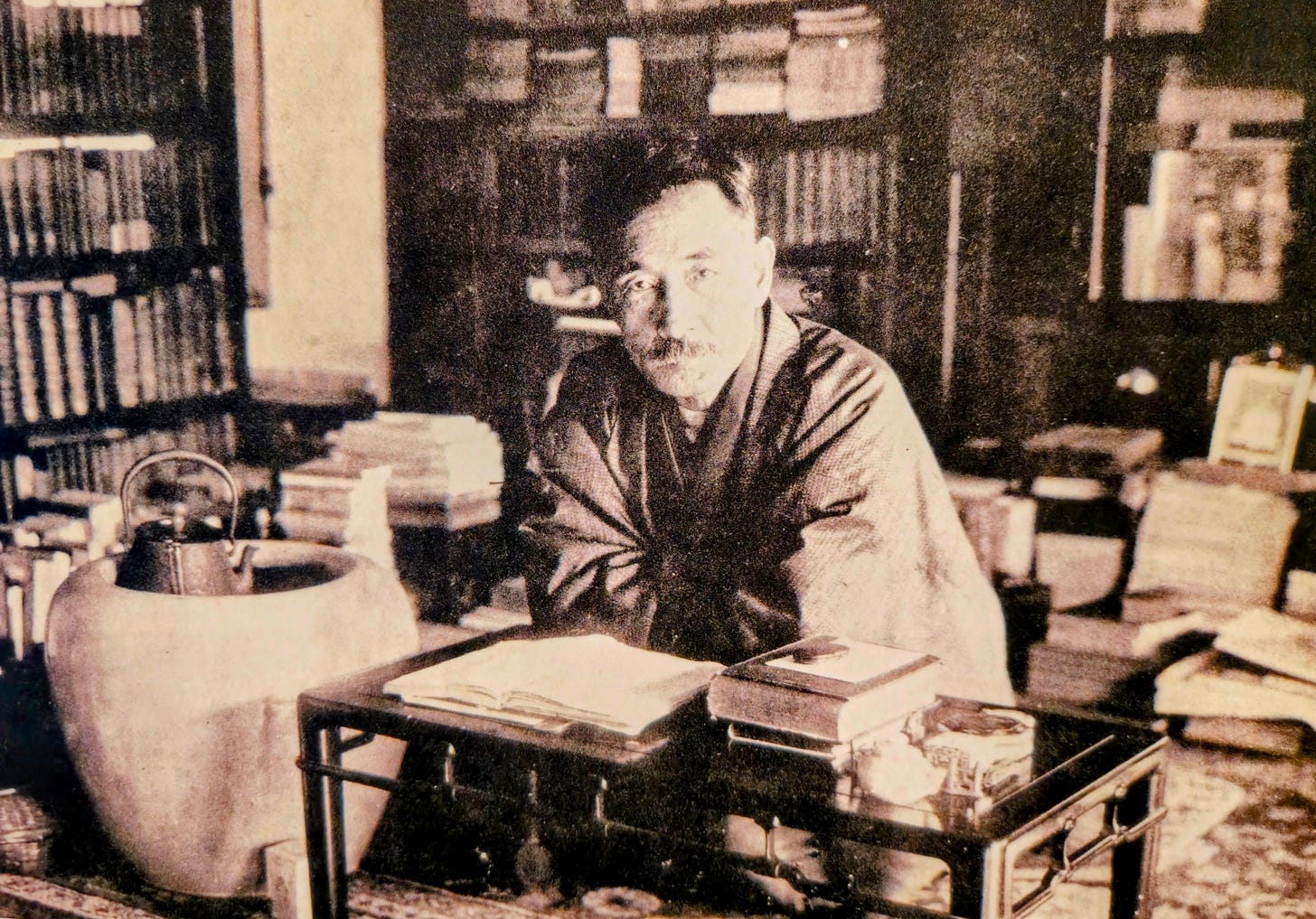

The museum itself is new and is on the site of the house that was Sōseki’s home for the last nine years of his life. Here, Sōseki regularly met with other writers in a kind of salon each Thursday. He had a number of "disciples,” and his style influenced that of many later writers.

I thought back to the Charles Dickens Museum in London, which I visited in 2022, which was in one of the addresses Dickens used to live in. The original Victorian house gives you the chance to see the kind of conditions Dickens lived and wrote in. By contrast, this museum is purpose-built, airy, and light. Most of it is dedicated to explanatory panels about Sōseki, and there’s only one recreation of a room, the study where Sōseki studied and wrote. These are very different ways to memorialise a country’s most celebrated novelist, I thought.

The museum has images of cats in different poses throughout its interior, indicating the route to follow. This is a nod to Sōseki’s breakthrough book called “I am a cat” (“吾輩は猫であ: ”Wagahai wa Neko de Aru” 1905) which remains very popular. It satirises middle-class behaviour in Japan, and both the conceit and the writing remind me a little of Jonathan Swift.

As I walked around, I wondered whether I might also have anything in common with Sōseki. At first, just one small detail leaped out at me—he was, like me, born as a fifth son (though I avoided being given out for adoption). More significantly, perhaps, he developed an enduring love of English literature and, like me, taught both English language and literature at some stage in his life. He was also an art lover and enjoyed the paintings by Turner (among others) at the Tate Gallery in London much as I have done.

However, his time in London (1900–1902) on a Japanese government scholarship was not a happy time. Later, he would describe his time in these terms:

The two years I spent in London were the most unpleasant years in my life. Among English gentlemen I lived in misery, like a poor dog that had strayed among a pack of wolves.

His scholarship was not generous, and he seems to have felt his lack of funds acutely. However, he was somehow able to return with around 500 books, which are now among the collection of the books he owned at Tohoku University.

*

That afternoon, at the museum, as the Solstice sun began to set, the group of Sharp former employees moved off perhaps in search of refreshment elsewhere, and I wandered into the garden of the museum, where there was a memorial to the pet that had inspired his popular novel. From outside, the building looked elegant in the fading December light. Suddenly, I found Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No. 2 rolling around in my head, perhaps because the concerto haunts David Lean’s classic 1945 film Brief Encounter, which I’d recently rewatched.

Curious, I checked whether Rachmaninoff and Sōseki might have met in London. Rachmaninoff had apparently planned to perform his second concerto in London in 1899, though in the event he didn’t actually compose it until 1900-01 and wouldn’t play it there until 1908. But the work had its London premiere at Queen’s Hall in 1902. Sōseki probably couldn’t afford to go to many concerts, but I’d like to think of him sitting in the audience transfixed by the unabashedly romantic music. The two artists, both with long roots in the traditions of their art forms, moved their art into the 20th century in their different ways. Both suffered from mental health problems, but both have secured enduring reputations for their work.

As the sunlit faded altogether, I left the museum and walked back towards the metro station beneath some ginkgo trees, still in leaf and flashing under the street lights. Briefly, I imagined the ghosts of the two artists walking through the falling leaves, arm in arm, in deep conversation. Music by Rachmaninoff, words by Sōseki: I couldn't imagine a more beautiful way to end the day and to celebrate the start of astronomical winter.

This is wonderful, Jeffrey. You have a poet’s gift for making unexpected connections (Soseki and his museum., the Sharp company, its founder, the affinity group, your own introduction to classical music and love of Rachmaninoff, shared birth order, parallels between Japanese and English novelists, etc.) that is simply remarkable. All of this is informed by your imagination and the depth and breadth of your intellect.

Coincidentally - speaking of famous cats in literature - I’m working on a post about Britten’s ‘Rejoice in the Lamb’ and its brilliant curation of the words of Christopher Smart. “For I will consider my cat, Joeffry” of course! I’m also - as a result of some insights gained from Maya C. Popa and her Conscious Writers Collective - rereading Conrad’s The Secret Sharer and Heart of Darkness.

Thank you for sharing the photos. Love the ginkgo trees with their golden leaves.

I hope you are enjoying the holidays. Wishing you a glorious New Year.

I happen to have have I Am a Cat sitting on my bookshelf and I'm going to read it next. Thank you.