Explaining Japan

A Review of Diane Hawley Nagatomo’s debut novel ‘The Butterfly Café’

One evening at a dinner in Shanghai, the man sitting next to me told me that he was writing a book that would “explain” Japan better than any foreigner had done until then. He turned out to be a very distinguished anthropologist, who also explained that some societies are simply more complex than others and that Japan was among the most complex (as I recall, he described the US and China being relatively easier to describe).

I am not qualified to pass judgement on that, but I have certainly found that of all the different countries I have lived in - and it’s been a few - Japan seems to have the biggest explaining industry dedicated to it, in terms of books, articles blogs, etc. This was especially true back when everyone wanted to learn from Japan’s astonishing economic and technological rise in the 70s, 80s and 90s. But the industry still exists.

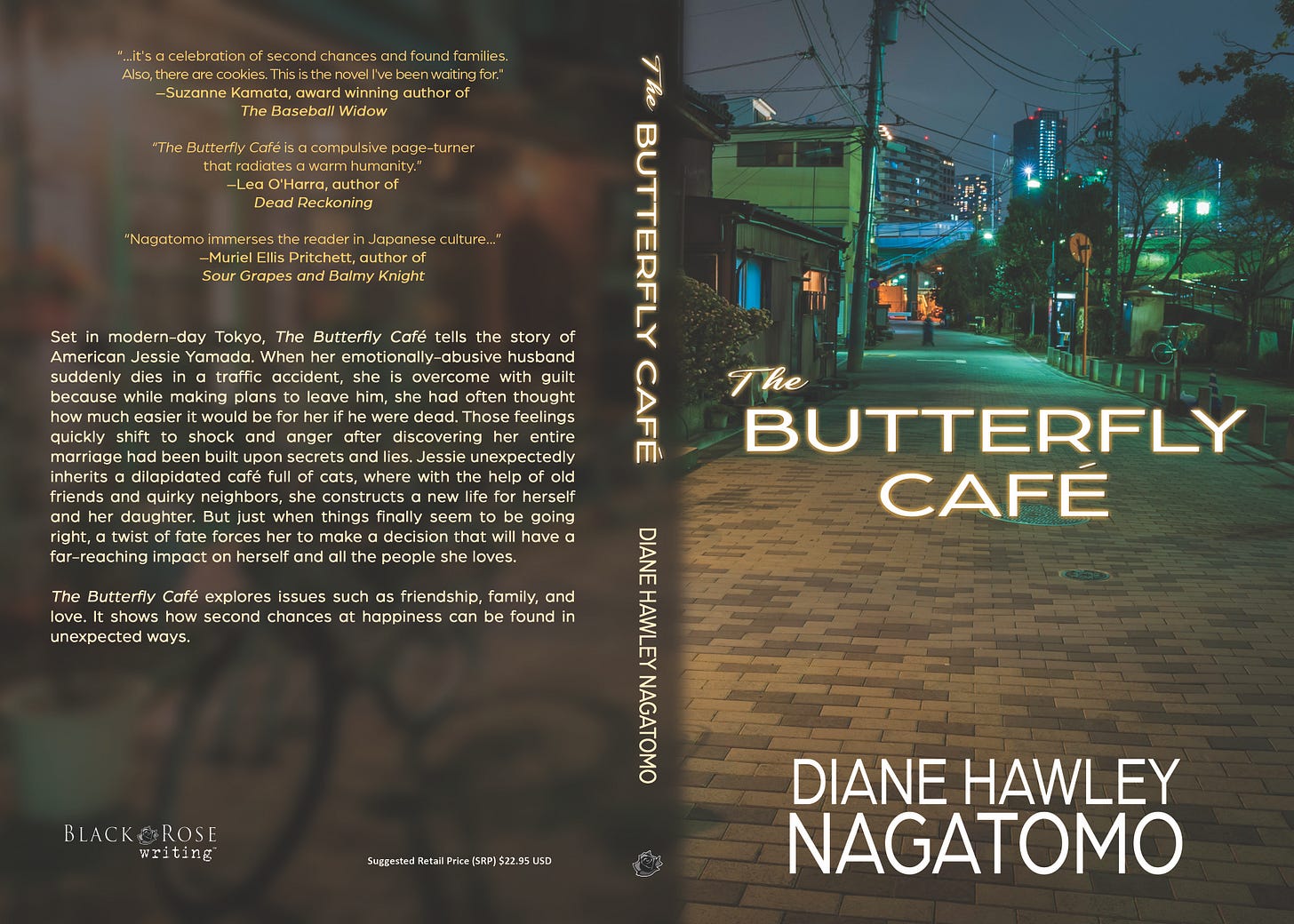

Diane Hawley Nagatomo’s excellent debut novel, ‘The Butterfly Café’, partly belongs to that explaining industry, as I will discuss below. But it’s also a well-told story, with sympathetic protagonists and the narrative moves along at a good pace with plenty of twists and turns. I really enjoyed it.

Any time I read a novel set in a different culture from the author’s, I think of famous examples such as ‘Under the Volcano’, ‘The Good Earth’ and ‘The Levant Trilogy’. Such novels tend to come freighted with expectations that they will somehow make the local culture more accessible to the reader, who is herself usually a foreigner to it.

This is a rather fraught exercise, of course, with the risks of bias, an agenda or plain old misunderstanding all creeping in. Pearl Buck’s ‘The Good Earth’ actually gets a mention in the book under review, as being the start of the main character’s interest in Asian culture: “For Jessie, it was a tattered copy of Pearl Buck’s The Good Earth that she had found on her grandmother’s bookshelf that set her interest in Asia in motion.” She quickly adds, acknowledging the issues: “’I know that book is problematic from all sorts of viewpoints, but I was thirteen, and it had a huge impact on me.’”

I’d guess that Olivia Manning’s ‘The Levant Trilogy’ has inspired less interest in 20th century Egypt than Pearl Buck’s in China or Malcolm Lowry’s novel about Mexico; in any case, I’d recommend giving Manning’s work a miss and heading straight for the wonderful ‘Cairo Trilogy’ by Naguib Mahfouz.

Nagatomo’s ‘The Butterfly Café’ avoids falling into the trap of “othering” Japan and strives hard to resist the orientalist gaze. It feels to me like a sympathetic primer on contemporary life in Japan, one which clearly comes a place of love and is obviously the product of a writer who has learnt to see the culture from the inside.

The challenge facing the foreigner-novelist in this context is to show rather than explain and to weave the abundant local cultural material into a book that reads like as a story rather than a textbook. ‘The Butterfly Café’ for the most part triumphantly achieves this through its strong storyline and interesting characters.

There are moments, however, when the urge to explain or display curiosities surfaces in the narrative. Given the author’s background as a professor at a high-ranking Japanese university, interested in culture and language, this is perhaps inevitable. One small example is early on in the novel when Jessie describes her best friend’s tendency towards culinary megalomania: “Jimmy always insisted on putting on a major Christmas production. Solo. Every single year, about halfway through the preparations, he would storm out of the kitchen and yell that he was giving up. That they were all going to be eating Kentucky Fried Chicken next year, just like everyone else in Japan.”

Overall, the scene effectively builds our sense of Jimmy’s personality as a good friend who’s prone to being over dramatic at times. The reference to KFC, however, strikes me as a little gratuitous, a detail not fully digested by the narrative (rather like the experience of eating too many of their nuggets). Momentarily, it seems that the desire to point out the mildly curious fact that some Japanese people eat KFC on Christmas Eve trumps the need to keep the hands on the accelerator pedal of the narrative drive.

“A sympathetic primer on contemporary life in Japan, one which clearly comes a place of love and is obviously the product of a writer who has learnt to see the culture from the inside.”

There are other examples, but these are fairly minor issues. You actually get the feeling that a strong inclination to explain has been wisely and skilfully suppressed or sublimated into the plot. One of the characters in the book, an American historian called Mark is pulled up by Jessie for mansplaining (though she doesn’t use the term). Mark replies with a degree of self-awareness: “Sorry. I’ve got this terrible tendency to over-explain things, especially anything related to Japanese history, whether a person wants to hear it or not.” This suggests to me that the author herself is aware of reining in a tendency to “over-explain”.

And much more often than not she gets the balance just right, such as when Jessie visits a couple who are her tenants in the house she has inherited: “Mrs. Tanaka served cups of green tea and sticky rice cakes filled with sweet beans in a Japanese-style room where the tatami mats were old but not tattered.” The focus in the writing here is on the charming Tanaka couple and their custodianship (without knowing it) of key documents of family (and national) history, with the details of the green tea, the sticky rice cakes and the tatami maps perfectly integrated into the development of the story. It’s a delightful scene.

If Japan provides the cultural backdrop of the novel, the theme that successfully drives the narrative along is that of family. The novel starts with escaping, accidentally, from a confining nuclear family arrangement and without really knowing she’s doing it, struggling her way towards a broader, more inclusive vision and experience of family as the story progresses. This works really well in terms of the plot, with almost every chapter moving Jessie closer towards this new experience of family, as revelation follows revelation about her husband’s family and their past.

Just as significantly, the theme of family takes away the focus from cultural differences and towards a broader human sameness; families may differ in composition and family customs may vary from culture to culture, but people everywhere belong to families and families belong to them. The melding of this the development of the plot with this broad, inclusive notion of family is, for me, a very impressive achievement and constitutes the great triumph of ‘The Butterfly Café’.

The dialogue is occasionally in need of further editing and the narrative voice is at times a little uneven, such as here: “It was a good thing that no one else from the company had come because the bar bill alone would have put Jessie in the poorhouse”. The use of “poorhouse” seems a slightly odd choice, the old-fashioned idiom not really consistent with the narrator’s usual voice.

However, these are minor quibbles against the overall achievement of a brilliant debut novel that deserves to have a wide audience. And for anyone travelling out to Japan, this is perfect reading for the flight over.

Note: a version of this review essay first appeared on LibraryThing and Goodreads. It was sent to me as an advance review copy (ARC). I had no contact with Diane before I wrote and posted the review. I hope to interview Diane for a future edition of English Republic of Letters.

Photos kindly supplied by Diane Hawley Nagatomo

A wonderful review. Very thorough and thoughtful. I found the part at the start about Japan being a more complex culture interesting as I had never considered the idea that some cultures were more complex than others.

It also sounds like a very good book, one I’m keen to check out.

Thanks :)

I’ve never been to Japan and haven’t sought out books about the country and its culture, but your review means that it is now on my reading list. You ask for other novels set in different cultures. If truth be told, I’ve neglected fiction books generally but I’m trying to remedy this. Stimulated by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s 2022 Reith lecture about Freedom of Speech, and her TED talk about the danger of a single story, I read some of her books, including Half of a Yellow Sun which is set against the background of the Biafran conflict. Thanks for your other recommendations.