William Hazlitt (10 April 1778–18 September 1830) was one of the greatest English essayists. His writing, I think, could have found a natural home on Substack. Sometimes when I read his essays, I feel frustrated that I can’t leave a comment. So today I decided to go ahead and do just that.

William,

When I re-read your fascinating essay On Antiquity, with its passionate hymn to the past and thoughtful meditation on time, I reflexively wanted to click on a “like” button, share it with other readers, and write about my own thoughts and experience. It’s the kind of thing we like to do in 2025.

In May 1821, when you published this essay in The London Magazine (I noticed on the preceding page a sonnet lamenting the recent death of John Keats), there was an option for a letter to the editor. But your editor, John Taylor, is long gone, and I’m not sure the current editors would print this.

So I decided to write this comment on Substack. I think other readers here may find your essay of interest. Your words may come from another time, but to me they feel very much of ours.

So, turning to the essay, let me say that I was really impressed with the arresting energy of your opening:

There is no such thing as Antiquity in the ordinary acceptation we affix to the term. Whatever is or has been, while it is passing, must be modern. The early ages may have been barbarous in themselves, but they have become ancient with the slow and silent lapse of successive generations. The ‘olden times’ are only such in reference to us.

Here you’re declaring a very obvious truth. But you’re right to remind us how the passing of time skews the way we view the world. Time is not a fixed progression in our minds.

And you go on to develop the thought with a typical flourish,

The past is rendered strange, mysterious, visionary, awful, from the great gap in time that parts us from it, and the long perspective of waning years. Things gone by and almost forgotten, look dim and dull, uncouth and quaint, from our ignorance of them, and the mutability of customs. But in their day—they were fresh, unimpaired, in full vigour, familiar, and glossy.

And I admire the way you bring the past to life:

The wars of York and Lancaster, while they lasted, were ‘lively, audible, and full of vent,’ as fresh and lusty as the white and red roses that distinguished their different banners.

You remind us that it’s hard to believe that “the sun shone in Julius Cæsar’s time just as it does now.” But we know that for an understanding of the past, we must somehow break through the barriers of time. I enjoyed reading about your wanderings on the site of an old Roman encampment in southern England, amid the “double lines of circumvallation (now turned into pasturage for sheep).”

I once did the same in Turkey, near the town you’d know as Halicarnassus, the birthplace of Herodotus, which is now a tourist resort and called Bodrum. There, seeking shelter from the strong sun, I stumbled across an ancient coliseum-style theatre in the middle of a woods where scrawny ewes now roamed and picked away at the vegetation in the shade.

I confess I want everyone to read your thought about how “if the sun breaks out, making its way through dazzling, fleecy clouds, lights up the blue serene, and gilds the sombre earth, I can no longer persuade myself that it is the same scene as formerly.” Sometimes your writing is just sublime, William.

I was intrigued by your notion of how periods or artefacts can jump around in our mental image of time according to their state of preservation:

That is old (in sentiment and poetry) which is decayed, shadowy, imperfect, out of date, and changed from what it was. That of which we have a distinct idea, which comes before us entire and made out in all its parts, will have a novel appearance, however old in reality,—and cannot be impressed with the romantic and superstitious character of antiquity.

I was curious about how you applied this to art:

The early Italian pictures of Cimabue, Giotto, and Ghirlandaio are covered with the marks of unquestionable antiquity; while the Greek statues, done a thousand years before them, shine in glossy, undiminished splendour, and flourish in immortal youth and beauty.

Given how much of a fan you are of early Italian art, I was slightly surprised by this. But I sense your meaning, and I agree there’s something truly timeless about those classical statues and their “undiminished splendour.” I don’t know how many of them I saw in Turkey, but I think they could people a small town.

“The perfection of art does not look like the infancy of things.”

And I love the way you summed this up:

Those times that we can parallel with our own in civilisation and knowledge, seem advanced into the same line with our own in the order of progression. The perfection of art does not look like the infancy of things.

I especially admire that pithy last sentence.

And I enjoyed how you brought the whole argument back to ourselves and our own struggles with time on a daily basis: “It is the sense of change or decay that marks the difference between the real and apparent progress of time, both in the events of our own lives and the history of the world we live in.”

Then my heart almost stopped as I read this:

The lone Helvellyn and the silent Andes are in thought coeval with the Globe itself, and can only perish with it.

Because it was only then I realised how you lived at a pivotal moment in the history of how we perceive time: It was just as Charles Lyell was preparing his monumental Principles of Geology, which would have a profound impact on our notions of time. In geological time, even the Andes or the Lake District, both of which I have walked in, are not eternal, not “coeval with Globe itself.” The Andes are a mere thirty million years old on a planet that has existed for over four and a half billion years.

But Lyell published his first volume in July 1830, and you died in the September of that year. You probably wouldn't have had the chance to read it. I wonder if you read a review of it. What would you have made of it?

I’m left reflecting on the chasm of difference in our thoughts that Lyell, Hutton, then Darwin and Wallace, and others helped to open up. Their work appears as a vast fissure in our history of time. It separates the traditional human or divine notions of time that you lived in, William, from the vastly longer periods of deep time that would become the bedrock of our thinking within a decade or two. In this sense, there is indeed a “great gap in time” between our time and yours.

William, I have to say that I loved this passage about old monuments:

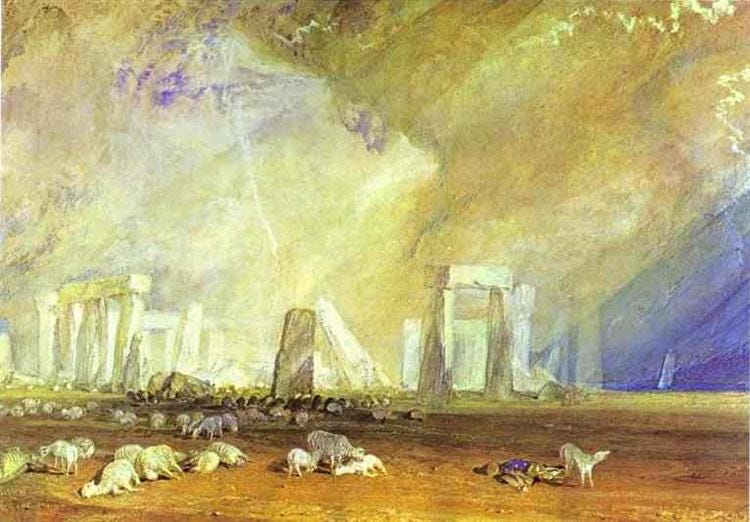

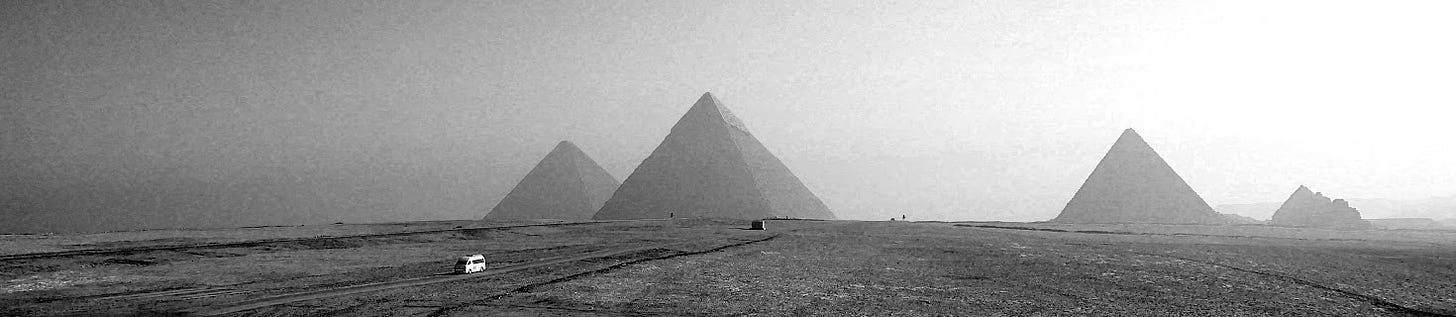

The Pyramids of Egypt are vast, sublime, old, eternal; but Stonehenge, built no doubt in a later day, satisfies my capacity for the sense of antiquity; it seems as if as much rain had drizzled on its grey, withered head, and it had watched out as many winter-nights; the hand of time is upon it, and it has sustained the burden of years upon its back, a wonder and a ponderous riddle, time out of mind, without known origin or use, baffling fable or conjecture, the credulity of the ignorant, or wise men’s search.

You were wrong about Stonehenge, as it happens—it’s probably about the same age as the Egyptian pyramids. But the beauty of your description of those old stones is so forceful that it creates a truth all of its own. There is indeed something compelling about the way Stonehenge reaches back towards a very distant past.

The comparison also reminds me of the time I visited Hattuşaş (or Hattusa), the ancient capital of the Hittites in Anatolia. Their original (“Proto-Hittite”) settlements date from about the same time as Stonehenge and the Egyptian pyramids, though Hattusa itself seems to have been built a thousand years later, or about three and a half thousand years ago.

On my ramble through those rough but impressive ruins, I stopped for a time to pay attention to the sound of the wind coarsely stroking the ancient walls. Then I heard the call to prayer drifting towards me from a nearby mosque. Normally, I would experience the music of the muezzin’s voice as something almost eternal in its distant floating beauty. But in that instant, among those ancient walls, it seemed almost modern; it was part of a culture that would only come into being one thousand seven hundred years after the end of Hittite rule. At that moment my notions of time and history seemed to shift like tectonic plates.

This comment has gone on too long, William. But before I end and invite others to comment (as I hope they will), I’d like to thank you again for your beautiful meditation on antiquity. As our scientists dive ever deeper into quantum systems, observing opposing arrows of time, one running forwards and one backwards, we begin to sense that past, present, and future are just mirages, rather as your beautiful hymn to time, your painterly poem of an essay, somehow, wonderfully, predicts.

“At that moment my notions of time and history seemed to shift like tectonic plates.” An extraordinary conclusion to a richly layered paragraph. Such a wonderful essay. As always, you weave your thoughts and personal experience into your knowledge of history, literature, culture, and now geology. I haven’t read Hazlitt, but you bring him to life both as an admired scholar and a friend. Thank you, Jeffrey.

Jeffrey, I have a strong suspicion Mr Hazlitt would have sat quite willingly with you for many an hour discussing, not only this vast question (illusion) of time but many, if not all of his other other essay subjects too. How clever of you to bring to the now the very theme he wrote of too... I thoroughly enjoyed this, thank you.