A constant treasure: On the road with Edward Lear

Some literature you discover, some you take with you.

*

Before I set off in 1988 to live and work in Quito, I set about my packing and preparations with my usual carelessness. I ignored most of the doctor’s advice about medicines I should take or jabs I should have for visits to Ecuador. I didn’t buy any special clothes for the varied climate and terrain. I just bundled what I had haphazardly into my impossibly impractical, pale blue vinyl, wheel-less suitcase.

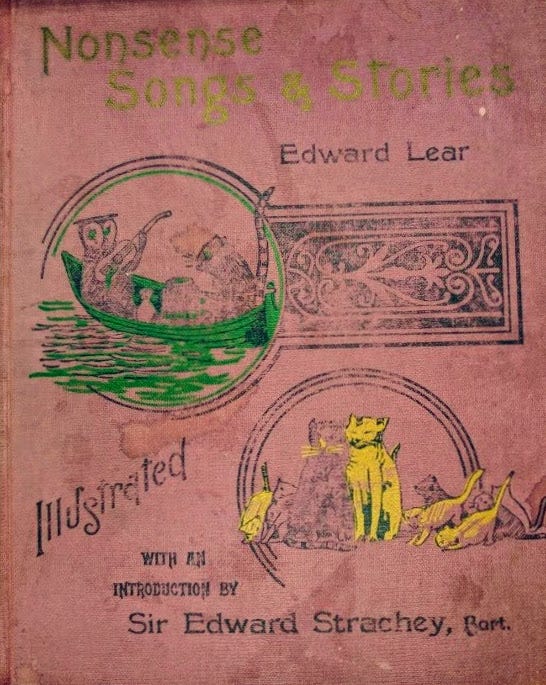

But on the eve of my departure, I popped into a local bookshop, slightly panicked of sitting through my first long-haul flight without anything to read. I was looking for a fat literary novel, the kind of thing I might have studied at university and would engross me for the thirteen hours or so on the plane. Most of what I could see was pulp fiction or coffee table books. But as I gazed in mild disappointment at the selection of books available, my eye was caught by a magenta cover with some interesting illustrations on the front: Nonsense Songs and Stories by Edward Lear. It was a hardback facsimile edition of the revised 9th edition from 1894 (the book had been first published in 1871), which included Lear’s own drawings. It wasn’t at all what I was looking for, and it certainly wasn’t long-haul reading material, but I knew I had to buy it. Into that suitcase it went.

*

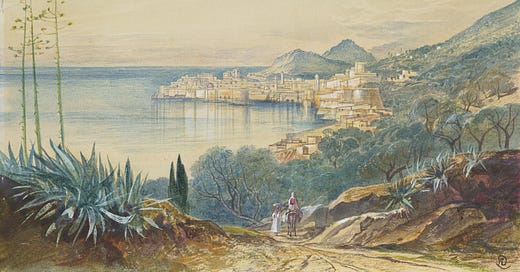

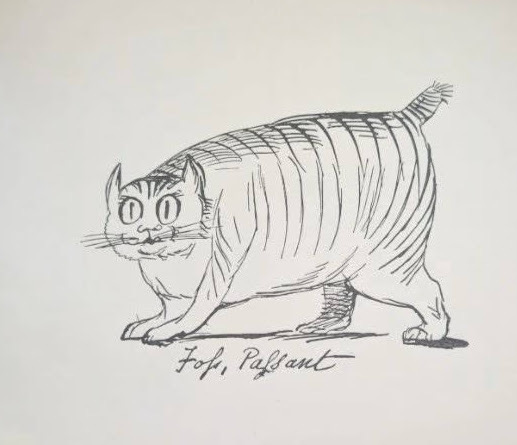

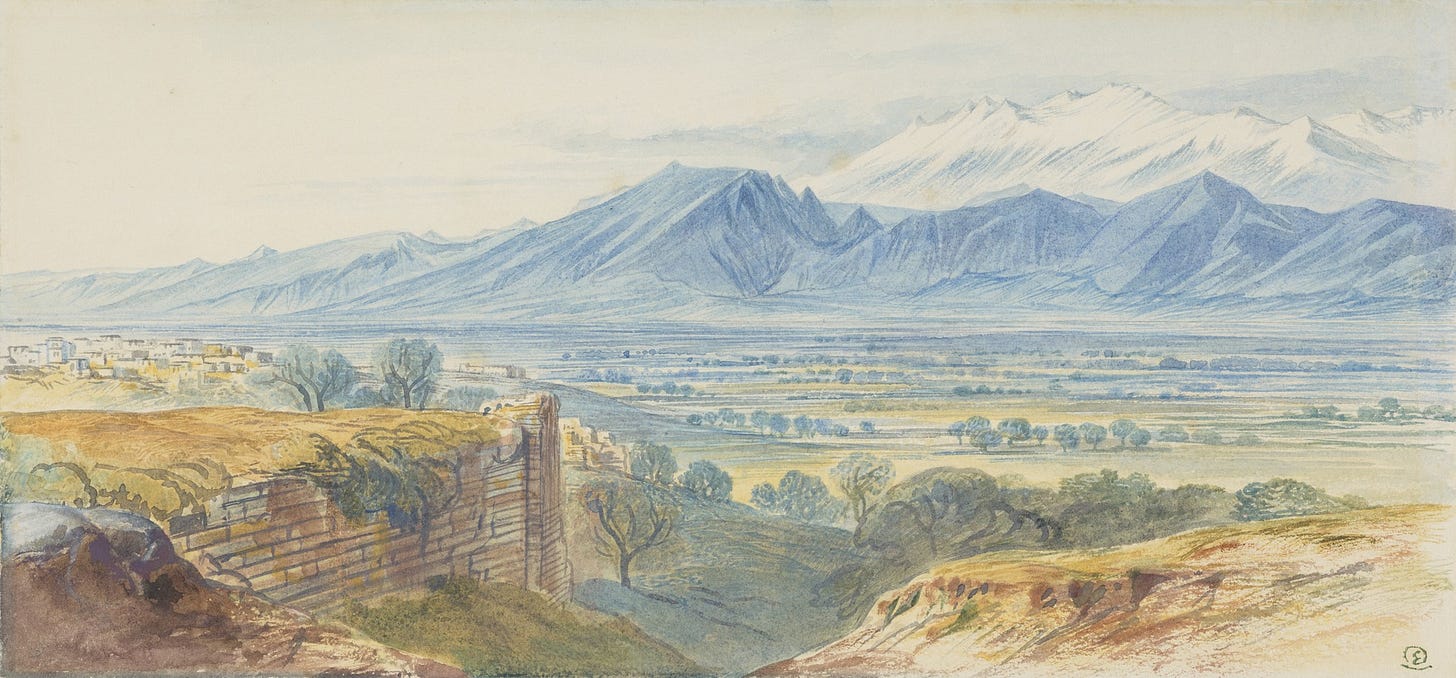

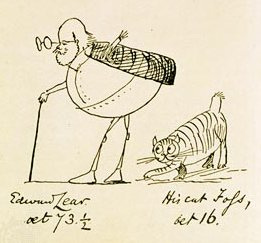

Edward Lear, born in 1812, died exactly 100 years before I set off for Quito. He was an English artist, illustrator, author, and poet, now known mostly for his literary nonsense in poetry and prose.1 He travelled extensively, rather like his characters. But in the 1870s, he settled in San Remo in north-western Italy, where he was accompanied by his beloved cat, Foss (1871–1887). According to one account, when Lear built a second house on his land, he made it identical to the first to avoid upsetting Foss.

*

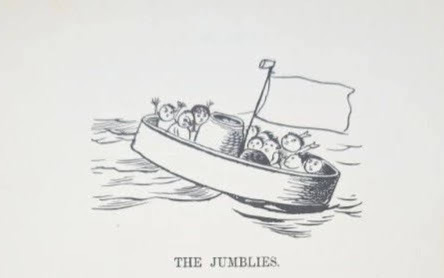

You might think this was an odd choice of mine—a heavy book of nonsense poems bundled into my luggage at the expense of climbing gear, mosquito nets, or malaria tablets. But while I had little idea then that I’d spend the next thirty-five years living around the world, something in the book called out to me at the time. Could it have been Lear’s ghost, offering himself as a guide? Was the author of The Owl and the Pussycat, The Courtship of the Yonghy-Bonghy-Bò, and The Jumblies trying to tell me something?

Of course not.

But the choice turned out to be a good one. I may not have followed the Jumblies as they went to sea in a sieve or found myself on the Coast of Coromandel, like the Yonghy-Bonghy-Bò. But the poems’ sense of restless adventure, their protagonists’ frequent insouciant resourcefulness, the romance, the humour, the sadness, and poignant moments of beauty have all helped to inspire, amuse, or sustain me over the restless years.

*

Wikipedia opens its page on “nonsense” with this description: “Nonsense is a communication, via speech, writing, or any other symbolic system, that lacks any coherent meaning.” Lear’s characters not only utter nonsense, but also their constant peregrinations seem to lack “coherent meaning.” Just why do the Jumblies sail away in a sieve? How did the Yonghy-Bonghy-Bò get to be on the Coast of Coromandel? And couldn’t The Dong with a Luminous Nose find a better way to look for the Jumbly Girl than wandering around at night?

I’m sometimes tempted to think similar things about myself. Where was I headed during all these years of moving from country to country? What was the plan and what did it all add up to?2

*

I still have the book with me (see photo above). It’s lived in more countries than even its well-travelled author. If

Two old chairs, and half a candle, -

One old jug without a handle

were “all the worldy goods” of the Yonghy-Bonghy-Bò, then this battered volume of Nonsense Songs and Stories became a permanent part of my own meagre stock of possessions. It’s been roasted by the tropical sun, exposed to life at 10,000 feet in the Andes, and has endured the snowy winters of Anatolia. It’s sailed across the Pacific Ocean at least three times. But it’s survived.

Even as I’ve discovered wonderful new literature in the places I lived—for example, the Tang poets of China, writers such as Jorge Icaza or Joaquín Gallegos Lara in Ecuador, Juan Rulfo in Mexico, or Yukio Minshima3 in Japan—I always had Lear and his odd assortment of heroes with me.

Travel for me was a choice, while for the Jumblies it seemed more like a compulsion and for the Yonghy-Bonghy-Bò, a sad fate. But in many ways, I shared their experiences—the voyages across sparkling new seas, the unfamiliar foods becoming everyday dishes, and foreign landscapes becoming home.

*

Some of Lear’s poems touch on loneliness, abandonment or loss. In his own mocking self-portrait, he writes:

He weeps by the side of the ocean,

He weeps on the top of the hill;

The disappointments of his life seem to find their shape in some of his poems, such as when the little birds fly away from the speaker in Calico Pie:

And they never came back to me!

They never came back!

They never came back!

They never came back to me!

I’ve repeated those words to myself in sadness a few times. I’m guessing you have, too.

But there are some happier travellers. Not only the Owl and the Pussycat, who enjoy their earlymoon voyage of a year and a day together, but there are also the eponymous heroes of The Duck and the Kangaroo, where an unlikely pair set off to travel the world together:

And who so happy, - O who,

As the Duck and the Kangaroo?

There’s been a Lear poem to echo every sorrow or joy in my life.

*

Lear was a privileged traveller, a white Englishman abroad at the very height of the power of the British Empire. It’s hard not to detect echoes of that (especially in his stories) and a glee at the exotic that might border on a form of Orientalism. But I think you’d need to be a very harsh critic to spend much time taking the gentle, playful Lear to task for this.

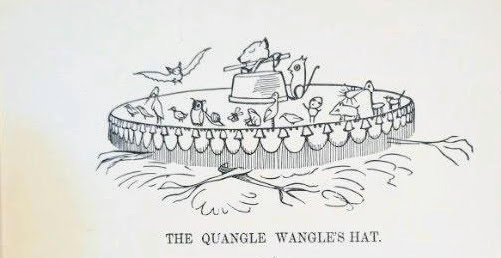

And for me, there’s an endearing inclusivity about his work, especially in The Quangle Wangle’s Hat. The Quangle Wangle is happy enough to live “on the top of the Crumpetty Tree,” but begins to wish it wasn’t such an out-of-the-way place. However, soon all kinds of creatures arrive, and he warmly welcomes them all to join him on his capacious sombrero:

And the Golden Grouse came there,

And the Pobble who has no toes, —

And the small Olympian bear, —

And the Dong with a luminous nose.

And the Blue Baboon, who played the Flute, —

And the Orient Calf from the Land of Tute, —

And the Attery Squash, and the Bisky Bat, —

All came and built on the lovely Hat

Of the Quangle Wangle Quee.

In Lear’s nonsensical universe,4 all are welcome; all have a space waiting for them.

*

One of Lear’s most famous poems was his own self-portrait, How pleasant to know Mr Lear, in which he turns his nonsense verse on himself:

He weeps by the side of the ocean,

He weeps on the top of the hill;

He purchases pancakes and lotion,

And chocolate shrimps from the mill.

He reads, but he does not speak, Spanish,

He cannot abide ginger beer;

Ere the days of his pilgrimage vanish,

How pleasant to know Mr. Lear!

An endearing quality of Lear is that he doesn’t seem to have taken himself too seriously, at least on the evidence of this poem. The sadness that seeps through some of his other poems is present here too, in what I take as a self-mocking but half-true description of himself weeping by the side of the ocean. But I also like to imagine a mischievous glint in his eye as he gently pastiches the romantic poetic trope of the lonely hero or heroine crying in the solitude of nature.

*

One of the last poems in my edition is Incidents in the life of my Uncle Arly, and it’s not hard to read it as another crack at a nonsense kind of autobiography. It starts with “Agèd uncle Arly/Sitting on a heap of Barley.” The poem then zooms through his life, his “squander’d” goods, his time subsisting like the “ancient Medes and Persians,” sometimes earning his keep by “teaching children spelling” or “at times by merely yelling.” And all the while, there is a tension between his constant discomfort—there’s a refrain of “But his shoes were far too tight"—and the consolation brought to him by his “constant treasure," the “ever-faithful Cricket,” which accompanies him.

There’s a slightly wistful feel to the poem, but it’s not a sad one. Despite the ill-fitting footwear, Uncle Arly, liberated from the burdens of his wealth, seems to have found some joy in his wandering life, especially through the company of the Cricket, whose chirping was “wholly to my uncle’s pleasure.”

The days of Lear’s pilgrimage vanished 100 years before my journey began. Even my copy of his Nonsense Songs and Stories is showing its age; I don’t think it has many more journeys left in it.

But the journeys it contains will live on forever. And I now recognise the nonsense verse of Edward Lear contained in this book—clutched in my hand or safely stowed away during the long voyages of my own pilgrimage—for what it was always destined to be: my own constant treasure.

Bonus track: The Jumblies by Edward Lear (read by me)

You can read a lot of Lear’s poems here: https://www.poemhunter.com/edward-lear/

Reader, you’ll have guessed that there was no plan. And just what it all added up to is one of the themes of the English Republic of Letters.

I plan to write about these last three writers one day.

I want to call it his “nonsensiverse.”

Thank you, Betty. I think Foss would be a really cool surfer!

What a great post, thank you so much. I have just finished reading The Sailor who fell from Grace with the Sea - Yukio Minshima, I still can't get it out of my head. The shocking beauty of it, blew my mind. I look forward to your post when it lands in my inbox. I had not heard of him before but randonmly happened upon the book in a charity shop and after reading the first page knew I had to carry on.