"I have one aim – the grotesque. If I am not grotesque, I am nothing."

Aubrey Beardsley, 1897

I’ve known Beardsley’s work since I was a student, but it wasn’t until I visited an exhibition at Tokyo’s Mitsubishi Ichigokan Museum last month that I found myself in a room full of his works.

Heavily stylised and dripping with decadence and simmering rebellion, they crackled with mood like a sultry summer’s day. It was not hard to recall why his work had appealed to my younger self.

But looking round the gallery space in Tokyo, I also found an enduring appeal in his art. Many of those on display were tiny book cover illustrations or sketches that took up little space on the gallery wall. But the distinctive, bold and – yes, sometimes grotesque – style shouted out at me from across the century and a quarter since he created his work.

Judging from the crowds in the gallery, he appeals to Japanese audiences, too. I can understand why. Not only did he dabble in japonisme, but his style may resonate with the sensibility of a land where cartoonish exaggeration is part of mainstream culture.

He even had a crack at shunga-style art; his work The Lacedaemonian Ambassadors was among those tactfully hidden away in a curtained room from which younger viewers were banned.

Beardsley was born in Brighton, England, in 1872. He would die of tuberculosis at the age of 25 – it’s hard not to compare his fate to Keats or indeed to the Japanese poet Shiki, who I wrote about here.

His family had inherited some money, but this was lost while he was young, and they struggled financially thereafter. However, Beardsley was able to get a huge boost to his self-belief as an artist through a meeting with the then “rock star” artist Edward Burne-Jones, who told him, “There is no doubt about your gift; one day you will most assuredly paint very great and beautiful pictures.”

Beardsley benefited in a more concrete way from his mother’s and sister’s dedication to his artistic education, and he enrolled for evening sessions at Westminster School of Art. Nevertheless, he still had to work to help support the family’s income, finding himself working as a clerk in an insurance firm while still in his teens.

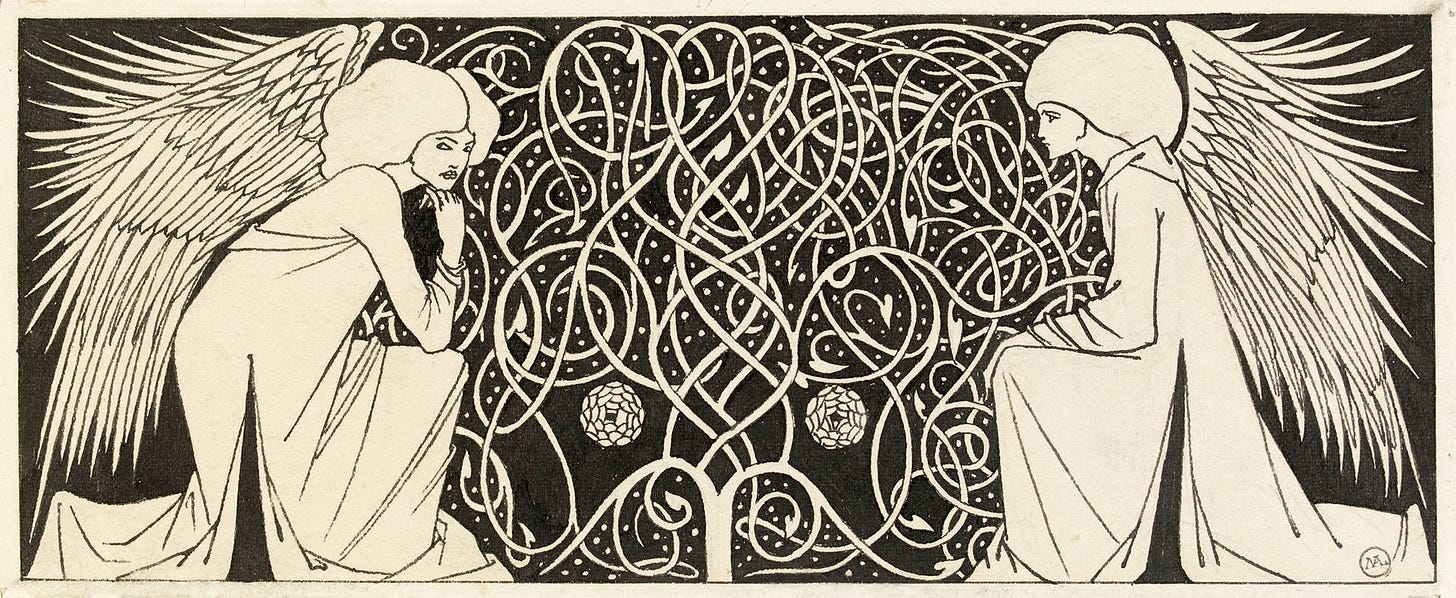

His first breakthrough came when he landed a commission from the publisher JM Dent to illustrate Le Morte D’Arthur, Sir Thomas Malory's late mediaeval version of the legends of King Arthur and his knights of the Round Table.

He produced some stunning work for this (I especially love the two angels in the illustration at the top of this post). And he felt emboldened to give up his job in insurance. 1

The grind of freelancing – those deadlines! – apparently wore him down. But the work he took on arguably allowed him to shrug off the influence of Burne-Jones and develop his own style.

The exhibition dedicated a large amount of wall space to the extraordinary images he produced on commission from the publisher John Lane to illustrate an edition of Oscar Wilde's play Salomé (1894).

Not only was he producing work of stunning quality; he was becoming, for such a short-lived artist who struggled with illness, extremely prolific. A surprisingly practical attitude seemed to help:

“Asked if he had ever experienced visions, Beardsley replied, ‘No. I do not allow myself to see them except on paper.’ For an artist so stubbornly fanciful, Aubrey Beardsley had a surprisingly realistic streak…And although it could not keep him alive, it gave him an extraordinary ability to work in the shadow of death for much of his short time as an artist.”2

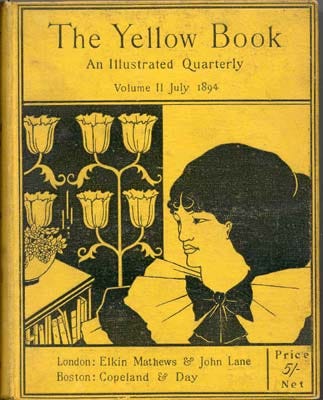

Beardsley’s promising career came crashing down when Wilde was arrested for gross indecency and was (wrongly) believed to be carrying a copy of The Yellow Book (a periodical that Beardsley also worked for) when arrested. In the moral panic that followed, Beardsley was dismissed as art editor of the periodical.

It was the kind of blow that might have ended the career of someone less driven. However, he carried on with his work, making new contacts and patrons, and he soon went on to co-found a new periodical, The Savoy.

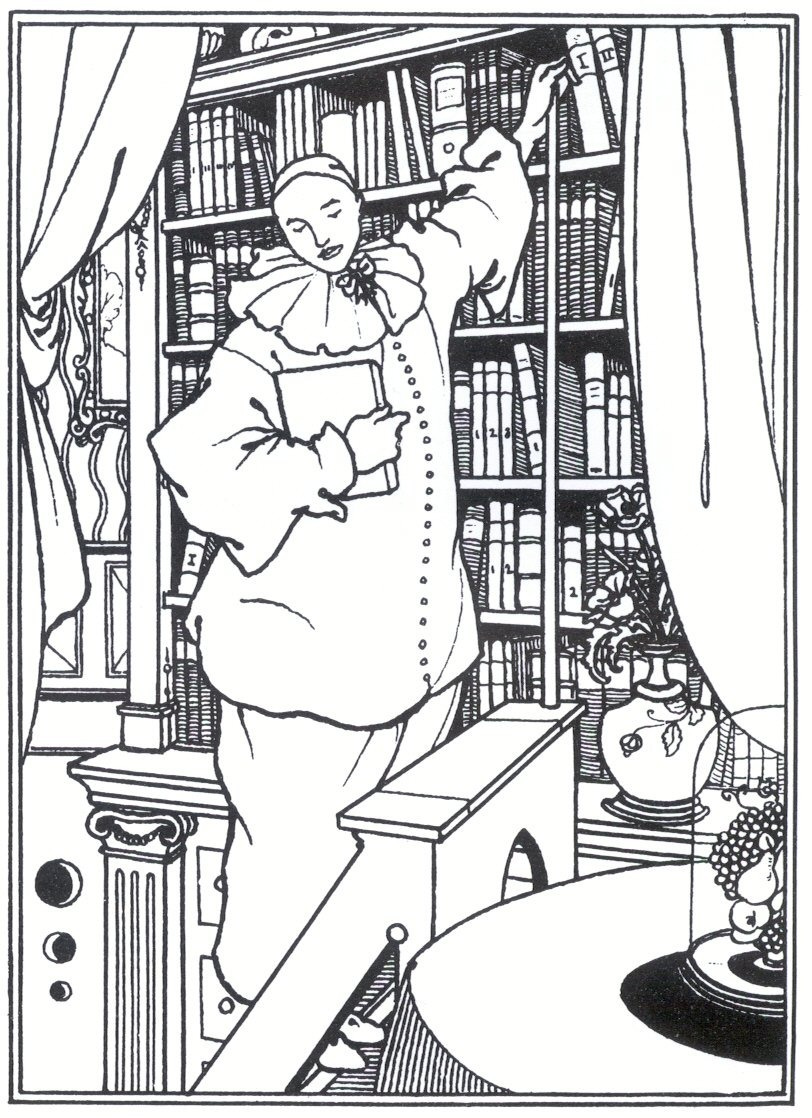

His style began to change, supposedly under the influence of the French artist Jean-Antoine Watteau. You can certainly see a new pictorial style in the illustrations to Alexander Pope's mock-heroic poem The Rape of the Lock.

In place of the dramatic contrasts of black and white, these designs are crammed with intricate detail. The already established artist Whistler apparently said to him on seeing these drawings, "Aubrey, I have made a very great mistake – you are a very great artist."

His life was nearing an end, however. He went to France in 1897 in a desperate attempt to nurse his health but died there the following year.

His work seems to belong to a distinctive time and place in art history, the “fin de siècle” of 1890s London. It was “a time of decadence, of the rejection of moral and aesthetic convention in favour of perversity and scepticism, and of delight in the exotic, the scandalous, the sensational.” 3

One critic has summed up how intertwined his art was with that of his own time: “Beardsley’s career was remarkable, partly because (like much that was best about the period) it was paradoxically both highly individual and quite typical of its time and place.” 4

But however typical he was of his age, it was the distinctiveness and individuality of this “singular prodigy” that stayed with me as I withdrew from the crowded halls of the exhibition.

In such a brief career, he’d achieved both notoriety and the admiration of many fellow artists. As I emerged into the daylight and the bustle of a Tokyo downturn day, I wondered what he might have accomplished had he been granted a few more years of life.

This makes me think of TS Eliot, who was eventually “saved” from life as a bank clerk; of Wallace Stevens, who didn’t need saving from insurance; and of Charles Lamb, who certainly needed saving from the East India Company but had to wait until his retirement for his release.

The Death of Pierrot, by J. E. Chamberlin, 1981.

A quote from the curators of an earlier Victoria and Albert Museum exhibition. (This website is also a good place to see some more of Beardsley’s work.)

Chamberlin, Ibid.

Yet another fascinating read, Jeffrey. This is random thing to say, but I feel like you are my own personal history/art/culture teacher. And you you teach me about artists and writers I didn’t even know existed. It’s very cool. :)

Beardsley, I think, may well be an artist for the young, his cartoonish style appealing in its simplicity but filled with darkness and a strange, almost evil, veneer. I discovered Beardsley via the Pre-Raphaelites and the resurgence of Art Nouveau that came in the 1970s. I love the feel his work has of being very intricate and special bookplates.