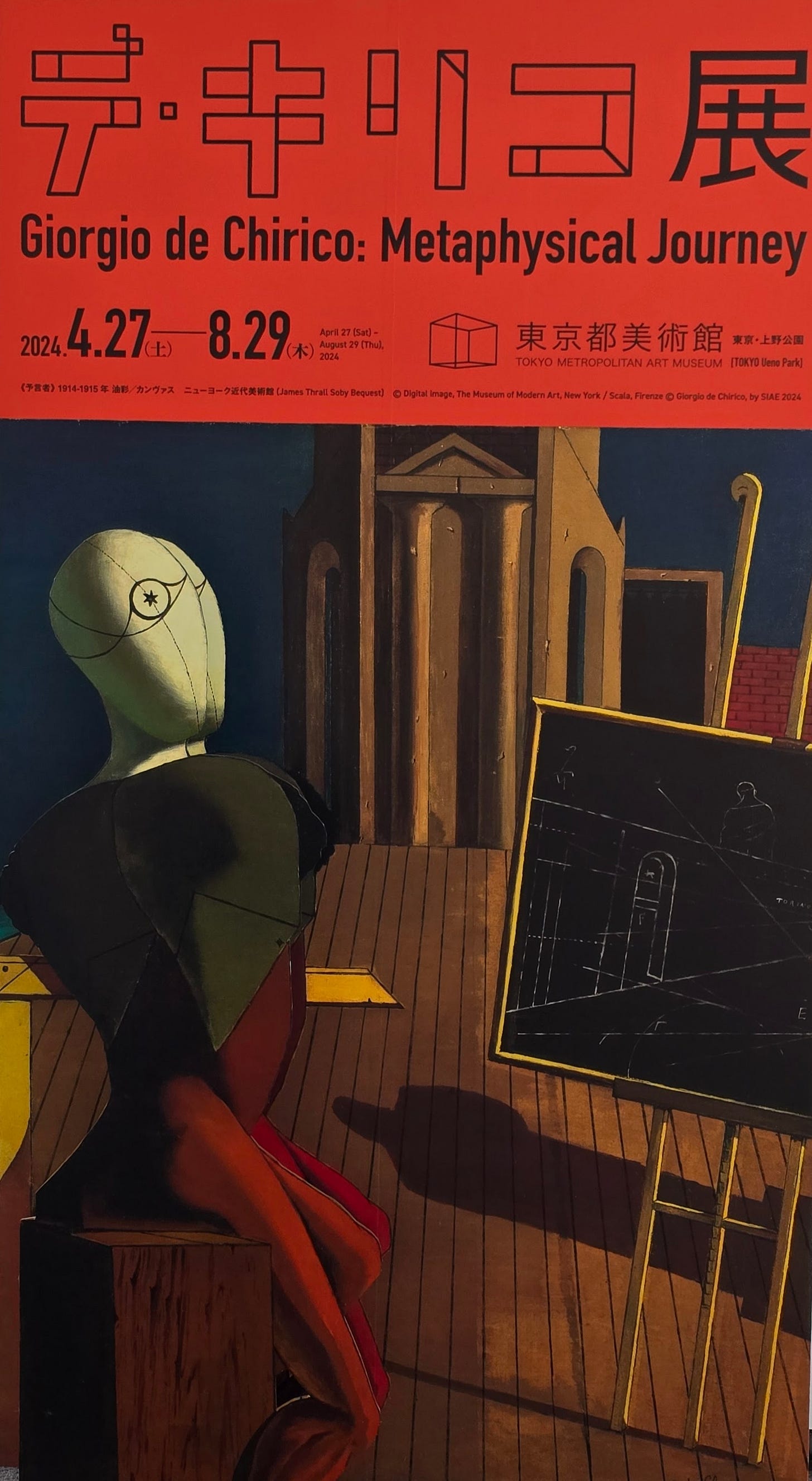

At the de Chirico exhibition

How a writer helped me to appreciate a master painter’s uncanny world

It was in the fierce heat of last August when I finally went to see the major exhibition by the Italian painter Giorgio de Chirico in Tokyo. When I first saw the announcement, I immediately wanted to go. I’d never seen an exhibition of this artist’s work, but I’d seen his work in art books, and they’d left with me a memory of colour and shape and a certain indefinable atmosphere of melancholy and mystery.

But when I noticed the exhibition’s subtitle of “Metaphysical Journey,” I confess my heart sank a little. While I feel intellectual stimulation is an important component of many art exhibitions, a “metaphysical journey” felt like a long haul.

De Chirico’s close contemporary TS Eliot (de Chirico was born in July 1888, and Eliot in September of the same year) ended his poem Whispers of Immortality (1919) with the dismissive lines,

But our lot crawls between dry ribs

To keep our metaphysics warm.

And I couldn't help wondering whether there would be a lot of “crawling between dry ribs” in this exhibition, so I hesitated about going. I’d also read of the painter’s affinity with Nietzsche. “I am the only man who understood Nietzsche; all my works prove it,” he once wrote. This boast was hardly encouraging. And anyway, just what was “Metaphysical Painting?”

But in the end, I went along.

And by the time I’d reached the cool of the museum, the late summer heat had burnt away thoughts of metaphysics. But there were over 80 works spanning de Chirico’s 70-year career. I couldn’t imagine looking closely at them all. Instead, I focused on 3 pairs or clusters of paintings.

First of all, I was really struck by the 1924 painting of Hector and Andromache.

Taken from the Iliad, this is a scene the artist returned to many times. In this case, the heroes are portrayed as mannequins, but the poses are very human, and I was struck by a warmth that I often didn’t find elsewhere in his work.

I have to add that the mannequins were a little off-putting at first, though I could see they were important in the painter's vision of the world—their silent melancholy chimes with the eerie quiet of some of the public scenes. However, the critic Magdalena Holzhey sees such figures also as “the blind seer of antiquity, a figure with visionary powers” (quoted in this interesting article by Lucio Giuliodori).

And according to Giuliodori, citing the artist’s brief experience of war, a figure of a dummy could also symbolise a person who feels “physically and psychologically harmed, helpless and powerless, at the mercy of events. Such a man is in the throes of a kind of dehumanising effect, in so far as he is living in a world ruled by madness, rather than rationality.” 1

To me, the 1924 painting didn’t seem, by the artist’s standards, dehumanised, but that was in contrast with the 1968 painting of Hector and Andromache in front of Troy.

I found this later work less moving; it put me in mind of two robots posing for a selfie. There is a lack of emotion in this depiction of a famously moving scene from the Iliad, especially when compared with his earlier treatment of it and those of more traditional artists like Angelica Kaufmann This version is more ETA Hoffman than Homer.

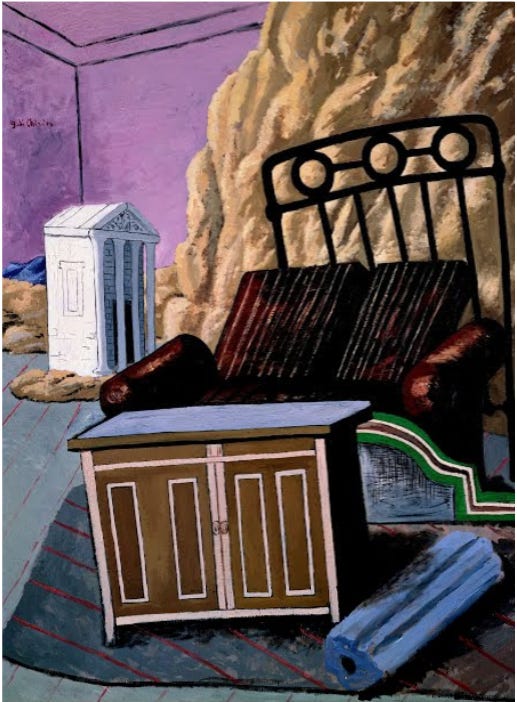

After leaving behind Hector, Andromache, and the mannequins, I became fascinated by a couple of works focused on furniture. Yes, furniture. One of them is called, with bold literalness, Furniture in a Room (1927).

What jumped out at me here was the astonishing array of opposites in this painting. There exterior and interior (with the temple, even the mountain in the room). There’s the human/intimate (cupboard) and the sacred (that temple again). There’s artificial and natural. Old and new. Beautiful and ugly. And there are contrasting textures, shapes, and colours: hard vs soft, dark vs light, square vs round, square vs oblong, and sharp vs blurred. Among all this tension between opposites, an unlikely and pleasing harmony is conjured up.

I then walked over to explore Furniture in the valley (also 1927).

Here I detected a different kind of opposition at play in the way that these two empty chairs are set against each other. The tension feels like a battle between immutable forces, and the result is not harmony but an oppressive kind of stalemate. I also wondered what might be hiding in that wardrobe. Again there is a temple, but this time it’s distant and hovers in the background, an echo of a painting by Poussin. Was this absorbing but unsettling work toying with the possibility of some kind of enlightenment or salvation or grace—but muted, distant, maybe unreachable?

The final cluster of works that grabbed my attention were some famous paintings set in public places, often with towers looming over them. I loved Piazza d'Italia (1913) with its long shadows and classical architecture and air of mystery, and especially the gorgeous orange/red of the interior parts of the buildings. There’s a dreamlike quality, but it’s a real place, and all of the figures and buildings seem broadly “realistic.”

And the same inviting colour, perhaps a little darker, can be seen in The Red Tower from the same year.

This place is fictional, I understand. But there is something solidly satisfying about the tower. If it doesn't exactly promise sanctuary, it seems to hold some kind of promise of better days to come. This is in contrast to the (for me) more sinister statue of a figure on a horse, which is partially obscured by a wall and is immersed in shade. The raised leg of the horse makes it seem that the statue is forever moving into full sight. This might be taken as a sign of potential, of being as becoming. But it also suggests a kind of incompleteness to me, a frustrated creation that never becomes complete and lurks just out of sight and our control. 2

Tiring slightly, I soldiered on and came across a later work, Piazza d'Italia with pink tower (1934) which is similar to The Red Tower. Indeed, it’s been called one of de Chirico’s “copies” of earlier paintings. But for me, there is a huge difference in the way that the shadow falls across the space in front of the tower (not from the tower itself). In the later painting, the shadow cuts a diagonal line across, leaving one whole building and part of the street bathed in sunshine. It’s an altogether less sombre work than the earlier one and suggests to me the immense skill and power at play in the painter’s manipulation of light.

In Mystery and Melancholy of a Street (1914), we see a similar diagonal line, this time from right to left, that reveals one building and the figure of a girl playing with a hoop.

There’s an empty cart—a horsebox, perhaps? There's a shadow from the main square of a figure we can’t see. Is it a statue? A human figure? The horse that’s been let out of the box? There is shadow, and there is a mystery, and these seem to hold the “melancholy” of the painting’s title in check. And the girl’s hoop and her raised leg also seem beautifully poised and balanced in this hauntingly lovely work.

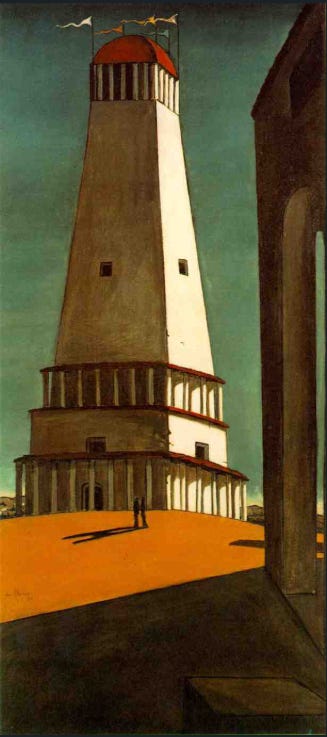

More portentous, though also attractive, was Nostalgia of the Infinite (1913).

Apparently, the tower draws inspiration from the Mole Antonelliana, a landmark tower in the city of Turin. Again, I love the orange-red colour, and I enjoy the flags that flutter in the breeze at the top.

The enigmatic tower, though, utterly dominates the painting and seems to push us to one side while remaining half in shadow and half in the light. What was it telling us? Wearying a little, I began to feel lost in the artist’s games with symbols. De Chirico once wrote:

“We who know the signs of the metaphysical alphabet know which joys and pains are enclosed within a portico, the corner of a road or even in a room, on the surface of a table, between the sides of a Box. The limits of these signs constitute for us a kind of moral and aesthetic code of representations and moreover, we, with clairvoyance, construct in painting a new metaphysical psychology of things.” 3

Whew. We seem to be finally crawling through some dry ribs here. I felt almost overwhelmed to be a witness to so many mysteries, to countless questions without answers.

But then one of my favourite books, The Book of Disquiet, popped into my head. Could it offer a key for me to access the work of de Chirico? As it happens, the author, Fernando Pessoa, was born in June 1888, just a month before the painter. Could he be my guide?

The Book of Disquiet (published posthumously in 1982) unfolds like a fever dream through the streets of Lisbon, where a bookkeeper named Bernardo Soares, Pessoa's “semi-heteronym”—just one of his many literary alter egos—chronicles the exquisite melancholy of existence within the city, weaving together fragments of philosophical reverie and quiet desperation, turning boredom into art and even a state of potential.

Near the beginning of the book, in the 3rd section of this “factless autobiography,” Soares/Pessoa writes:

I love the stillness of early summer evenings downtown, and especially the stillness made more still by contrast… the sad streets extending eastward from where the Rua da Alfândega ends, the entire stretch along the quiet docks—all of this comforts me with sadness when on these evenings I enter the solitude of their ensemble... There is no difference between me and these streets, save they being streets and I a soul, which perhaps is irrelevant when we consider the essence of things. There is an equal, abstract destiny for men and for things; both have an equally indifferent designation in the algebra of the world’s mystery.

I began to see Pessoa’s engagingly melancholic book as a counterpart to the very serious art project of de Chirico: to tease out a new essence of things following the departure of older meanings. Pessoa tried to obliterate himself as an author through adopting so many personas, but in the Book of Disquiet, he’s still there, puzzling over the “algebra of the world’s mystery” in a universe that has lost its significance. De Chirico, similarly confronted with the death of older beliefs and metaphysics, seeks the possibilities of new meanings in the objects which he depicts or creates and then reassembles in different patterns of colour and light, creating his own dazzling puzzles.

Pessoa’s The Book of Disquiet and de Chirico’s paintings surely share a sense of existential unease. But I don’t see these almost empty civic spaces as only places of unease or disquiet. They’re also places of potential or promises. Places where you can be still and watch the world in orbit around you. Places where there is light and colour and where ordinary life can happen beneath the historic towers, where we can follow our individual routines that lead gently like jetties towards possibilities shimmering just out of sight. I’ve felt like this myself in places as different as Chambéry, Valencia, and Yokohama.

Maybe after all, I thought, as I left the exhibition, it’s in these ordinary public places where we can find for ourselves the comfort of the solitude of the “ensemble” of the streets as in The Book of Disquiet?

Or, even, lift up our gaze to see de Chirico’s “joys and pains are enclosed within a portico, the corner of a road, or even in a room, on the surface of a table, between the sides of a box?”

None of this has really taken me much further in understanding “metaphysical painting,” much less the philosophy of Nietzsche. But fatigued though I was, I came away from the exhibition feeling a kind of secular awe for de Chirico’s rigorous exploration of his themes and even some kind of hope; the kind of hope whose shadow we might see approaching from around the corner as we walk with inquisitive purpose through the not-quite-empty streets of our towns and cities.

Like me, you may have heard a "myth" about the symbolism of military statues.

De Chirico, G., & Far, I. (2002). Commedia dell’arte moderna, p.32 (quoted by Giuliodori in the essay mentioned above).

thank you Jeffrey. I hadn't encountered Chirico before and this was a wonderful introduction. I felt like I was walking with you, at that tiring museum pace, engulfed by the color of the later pieces. I enjoy the way you look to contemporaries in different arts to inform each other, such an important recognition of how art forms in or against or through a culture.

A little de Chirico has always gone a long way with me. He’s a hard slog, all ideas and no obvious emotion. Looking at his work through your eues, I discovered an unlikely voluptuousness in his gorgeous use of color and shadow. The empty streets are haunting if you look at them closely. The two vaguely similar scenes are not really alike at all, and I’m amazed that anyone could think the artist was repeating himself. The interplay of massive solidity (arches, towers) and delicacy (flags, the girl with the hoop) starts a conversation in the mind. An artist as cerebral as de Chirico will never be a favorite of mine, but now I can appreciate him on his own terms.