At the Palace Museum

"A stately pleasure-dome decree": the new cultural district in Hong Kong

During the early 2000s, while I was based in Shanghai working for the British Council, I’d sometimes visit Hong Kong and would occasionally hear of the plans for the West Kowloon Cultural District (WKCD), which had been made in the late 1990s. In the following decade, when I was based in Tokyo, performing a similar role, I’d occasionally meet people involved in the still-unrealised project. In my mind, the place began to take on the aura of a legend, a kind of cultural El Dorado, even a version of Coleridge’s Xanadu. I wondered—maybe others wondered too—if it would ever be finished. 1

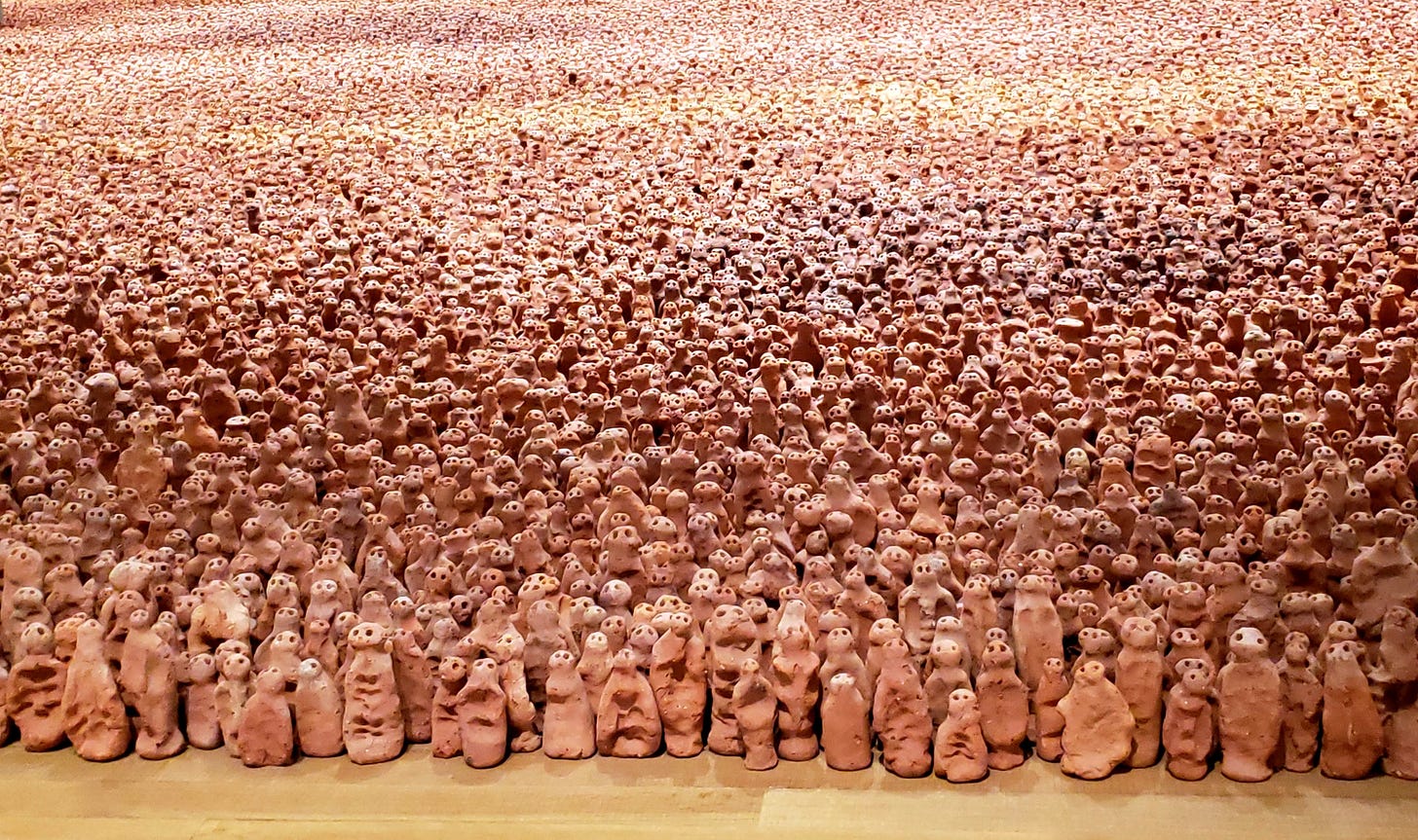

Arriving in Hong Kong to take up my post in 2018, I was happy—almost relieved—to see the reality of it. At that time, it was still mostly a building site. But gradually the institutions were built and teams assembled, and I remember in due course visiting the fabulous M+, a museum of contemporary art that had a wonderful opening exhibition of Chinese modern and contemporary art. It also displayed Antony Gormley’s astonishing Asian Field, which I’d had the privilege of being involved in—and above all seeing—when it was shown in Shanghai in 2003.

When I left Hong Kong to return to the UK in June 2022, it was frustratingly just days before the opening of the Palace Museum, which displays some of the riches of traditional Chinese art and artefacts. So I was delighted to find time during a busy work trip last December to make my first visit to the museum.

The WKCD is built on reclaimed land (there’s an echo in this perhaps of Coleridge’s “miracle of rare device”) and has magnificent views across the water of Hong Kong Island and further out into the South China Sea. The Palace Museum, apart from its contents, is a great place to admire the city from. And when I visited at the weekend, the whole district was full of people enjoying the scenery, the open space, the cultural amenities, and celebrating weddings, graduations, and, it seemed to me, life in general. It’s a wonderful space, full of life and colour and light.

The Palace Museum is a spectacular building, as I hope you can see from the photo above. It was by no means full when I entered, to my slight surprise. However, this had the advantage of giving me space to enjoy the contents.

The highlight for me was the first gallery, where the emphasis was on artefacts from the Forbidden City in Beijing, which itself is undoubtedly one of the most striking and remarkable places I’ve ever visited. 2 I’ve long had an interest in the early Qing emperors for their skilled statecraft and their dedication to and proficiency in the arts, especially Kangxi (r. 1661-1722) and Qianlong (r. 1735-1796). So it was exciting to see, for example, a collection of Qianlong’s favourite Tang (and Song) essays.

Almost certainly among those essays (I wasn’t able to check) are examples of the work of Han Yu (768–824), regarded as one of the masters of Chinese prose. He played an important role in the development of Confucian thought, especially the Confucian revival movement. A famous example of his style—and his bravery—is his vehement essay submitted to Emperor Xianzong (r. 806–820 CE) in 819 CE in response to Xianzong's proposal to parade a bone from the Buddha’s finger around the country. Reading this essay—technically a “report” to the Emperor—I am struck by Han Yu’s willingness to speak truth (as he saw it) to power, albeit in the most pithily elegant prose.

The essay is short, and Han Yu gets pretty much straight to the point, beginning with: "Your servant begs leave to say that Buddhism is no more than a cult of the barbarian people.” Ouch. He goes on to put the emperor straight on how to handle this foreign religion. 3 The emperor, Xianzong, was outraged, and Han Yu nearly paid with his life for his bluntness. However, he ultimately faced banishment to the south of the country rather than death. And he would return to high office after the emperor’s death, about a year later.

**

I was particularly struck by the exhibition’s highlighting of the Forbidden City’s role as a museum. As a former cultural diplomat (one used to waiting for official audiences like the envoys in the painting above), I was delighted to glimpse through the artefacts into the elaborate trade, cultural, and scientific exchange, as well as the international politics, of the time. These objects ranged from tribute gifts from Okinawa to a telescope from Britain, enamel techniques from Europe, and some extraordinary platform shoes. The sight of all these set off a foment of imagination in my mind, forging connections between the exhibits and my own (feeble) knowledge of the world, as any good exhibition should do.

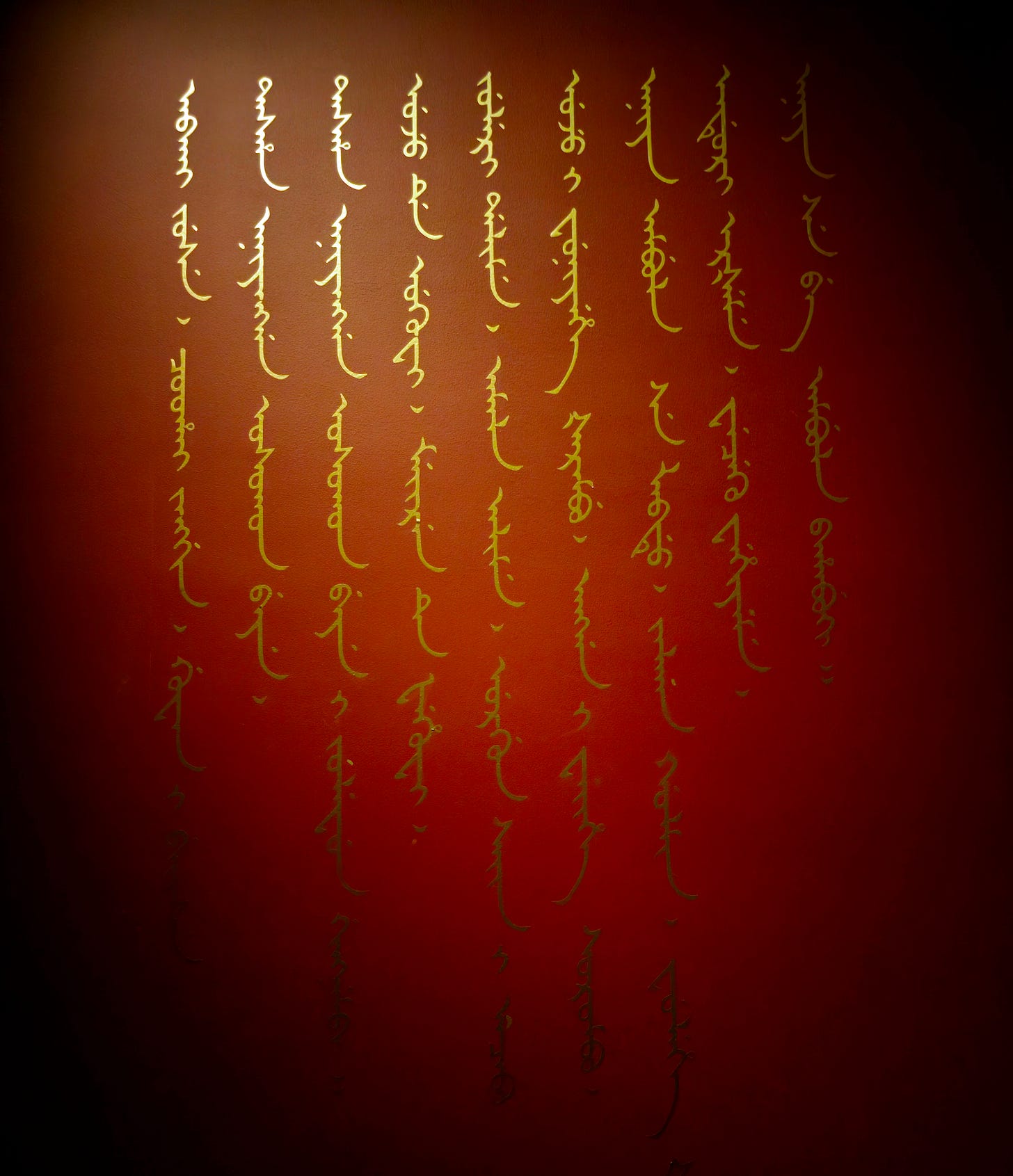

Part of the display was also a carefully crafted and illuminating look at a day in the life of a Qing Emperor (actually not just one day or one emperor). And I was astonished to be able to admire something that I had never seen before: the script of the Manchu language, beautifully presented on one wall. The vibrancy and multicultural nature of the early Qing court truly came to life during this visit and made me wonder what it would have been like to have been a cultural envoy to China in 1703 rather than in 2003. 4

You can visit the museum’s thematic exhibitions here via VR. And I’d strongly recommend visiting the HKCD and especially M+ and the Palace Museum in person if you ever find yourself visiting Hong Kong.

It was a long time coming, but worth the wait to see these pleasure domes, as in Coleridge’s vision, now aloft on

twice five miles of fertile ground

With walls and towers… girdled round.

Coleridge’s poem “Kubla Khan” begins:

In Xanadu did Kubla Khan

A stately pleasure-dome decree

And also intimidating, I suppose by design. It feels like the ultimate architectural power play, making it clear to the visitor the immensity of what they are dealing with.

I wonder what Qianlong, himself a Tibetan Buddhist who had to balance different belief systems in his multicultural empire, made of this outburst when he read it around a thousand years after it was written.

Though it would be hard to beat the astonishing energy I experienced while working in Shanghai in 2003-7, so I can hardly complain.

Thank you, Jeffrey, for taking me on a spectacular (albeit VR-style) tour of the museum, the city, and the history! Love it! ❤️

What spectacular photos! The very concept of that sculpture installation blows my mind. I’m curious: What exactly does a cultural diplomat do? Most of us are unaware that this career exists, yet for you it’s been a portal to all manner of discoveries. I hope you’ll get arlund to writing about this, if you haven’t already.