Just the worst time of the year

For a journey, and such a long journey1

I’d come to a crossroads, and I needed to make a decision.

This isn’t a metaphor.

As I thought about what my friends had told me that evening in our favourite bar the week before I set off, I couldn’t deny they’d made some good points. In fact, all the people I had befriended in Guayaquil, Ecuador’s largest city, thought I was crazy to be travelling alone on Christmas Eve.

“Why head off to Manta on Nochebuena?” they asked. They insisted I wouldn’t know anyone. (They were correct.)

Why didn’t I want to spend the night before Christmas with them? After all, I’d only just moved down from Quito earlier that year, and I’d been enjoying my time very much.

I genuinely liked this city. I liked its portales, the covered walkways in the city centre to shelter you from the burning sun or torrential rain, which often came on the same day. I loved the energy of this scruffy, restless port with its mangrove-covered creeks and slow-flowing river.

And I enjoyed the build up to Christmas—the growing sense of expectation amongst the children, the blend of genuine devotion towards the Christian festival combined with the carefree partying that made my previous homes seem grim and earnest in their Christmas build-up.

There was—and still isn’t—any logical reason for wanting to be on my own this Christmas. I was a man of 28. I was single and had been living around the world for 6 years. Looking back, it’s possible that I sensed other obligations growing, threatening to engulf me like the tendrils of the forest in The Sleeping Beauty. Maybe I wanted to stay awake a little while longer, before my one-hundred-year sleep?

My friends insisted I was foolish, even as I pushed on with my plans and bought a few last-minute Christmas presents for the people I was leaving behind. After all, the roads in this country aren’t exactly the easiest or safest to drive, as they told me. Why go all that way on your own if you don’t have to?

If I’m honest, though, even before I started discussing my Christmas plans with friends, I’d noticed a tendency for them to slip into imperative mode. “Deberías...” (“You should...”) was a word I was hearing a lot. For someone who had been used to making his own decisions since 18, as I had, it grated at times. My occasional exasperated response, “A mí nadie me dice lo que tengo que hacer” (“nobody tells me what to do"), had become a bit of a joke amongst us.

This was 1990, which meant that I was using a paper map to plot my course to the city of Manta, on the coast2. As befits the planning stage of any proper odyssey, I was debating the merits of the short route (more direct, but reliant on small country roads of uncertain quality) and the long route (better roads, but a path that would take me all the way to Velasco Ibarra, dozens of miles to the north, before a sharp left towards the coast).

There was another element to take into my great adventure: I would be driving a rattling 1972 Land Rover. With this in view, a shorter journey would be better. I’d already travelled down from the Andes in the vehicle. On that occasion, before I left Quito, I’d been dreading the descent on those narrow, winding roads, spiralling down one of the world’s highest mountain ranges, which had always seemed shrouded in mist whenever I travelled them by bus. But as it turned out, the descent was a sunlit breeze. What had completely confounded me were the potholes on the coastal plain as I trundled towards Guayaquil later that day. The Land Rover had shaken so much that I thought all the wheels were about to come off at once.

And yet, my friends urged me not to take the shorter road, that tempting cross-country turn off just past Palestina. “It takes you through the middle of nowhere,” they said. And they especially insisted: Don’t do it towards nightfall. In those parts, smack bang on the equator, the sunset varies only by a few minutes over the course of the year. Darkness would fall soon after 6 p.m. You don’t get a lot of twilight.

I took all their advice and listened to all the "deberías,” and I set off on the road out of Guayaquil as early as I could, sensibly resigned to going the longer, slower way. As it happens, the first part of the journey was common to both routes. So it wouldn’t be till later that I’d have to make a final decision between the short and long routes.

Two routes diverge on a map, and I chose…

It was hot and sticky as I drove out of the city around 2 p.m. I had my map on the dashboard, with the long route and the short one both marked. I hit some heavy traffic as I left the outskirts, making my progress a bit slow, but I was on my way. I really hoped for a smooth ride. I reminded myself that this wasn’t the road that had left me a wobbling wreck after my drive from Quito. There ought to be enough smooth tarmac to plot an even course.

Finally out of the city traffic, I could settle into my seat a bit more. The weather for my trip was in a place of transition: the relative coolness of summer that the Humboldt Current brings to this part of the Ecuadorian coast was now at an end, and the winter heat and torrential rains were approaching.

As all road trips call for music, I used my vehicle’s one luxury, a cassette player, to shuffle through Pet Shop Boys and Tracy Chapman. After being on the road for an hour, I was getting into the swing of the journey. No drive was ever boring in those parts. There was always plenty to see. Brightly-dressed women walking to a family gathering or to meet their boyfriends; young men in bright white shirts hoping to dazzle an admirer or two; older men in their guayaberas, chewing the fat with a friend. Life happened on the roadside.

Then there were the sounds and smells; the incessant drum and whirr of insects in the tropical coastal forest, the acrid aroma of the drying cacao beans on the side of the roads, and the sweet and sour odour of fallen tamarindo pods. Driving with the window open and with every bump in the road fully tangible through every vibration of my ancient chariot, this journey was a kind of enchantment in every sense, an intoxication that I’d come to associate with travel in Ecuador.

It was only when I’d listened to The Cure’s album Disintegration a couple of times that I realised that something was wrong. The cassette was playing continuously, stuck in a loop, instead of stopping. I pulled over and tried, unsuccessfully, to fix the problem. A little frustrated, I drove off, trying to make up for lost time. But in the end, I figured it was just a broken cassette player. And besides, I liked The Cure.

By now, the afternoon was well advanced. I got to Palestina, the small town just south of where the short road turned off from the main road, just as the afternoon light began to mellow and refract softly through the roadside plantations. I’d soon need to make a final decision.

And then it was upon me, a signpost signalling a road heading west, optimistically marked “Manta”. I stopped by the side of the road again for several minutes, to the amusement of the many passers-by, mulling the two options on my route. They were wondering, no doubt, what this gringo in his battered old vehicle was up to.

And I was wondering: should I take the longer route?

Should I do what everyone had told me that night in the bar would be the only sane thing to do? I should, shouldn’t I?

Deberías.

Or would I turn left, to cut my journey? Perhaps show everyone I knew what I was doing?

No one tells me what to do.

I got back in the car, rejoined the traffic heading north, and then abruptly yanked the steering wheel to the left. I was heading cross country to the coast, taking the road I'd been told I should avoid.

Well, the gringo was going to show his friends that he could handle a road trip on his own terms.

The terrain soon became more hilly. That didn’t bother me. I’d driven in the Andes, after all. But it slowed me down. I could hear my friends’ voices whispering in my head that this wasn’t the road for me. The heavy, slightly underpowered old Land Rover wasn’t made for rapid ascents, after all. But on I drove.

Before long, I noticed that the sun was close to setting. In a few minutes, it would be dark. Unlike the main road, there weren’t many houses to be seen here, and very few lights. The road was now just a single, winding lane. I had miscalculated the time it would take me to get here. Should I turn back?

My hands were getting a little clammy on the steering wheel, despite the cooler air. I was no longer quite sure of myself, but I pressed on.

Darkness fell like a solemn event. The air felt cooler at this elevation. There was no moon, but before long, stars were brightly visible. I’d switched off the music a while ago, tired of hearing the same songs playing over and over—it was like listening to some crazy student dorm neighbour. But eventually, if only to have the sound of other voices for company, I switched the music back on.

I drove carefully, though I saw no other vehicles on the road. There was, in fact, very little of anything except the darkness.

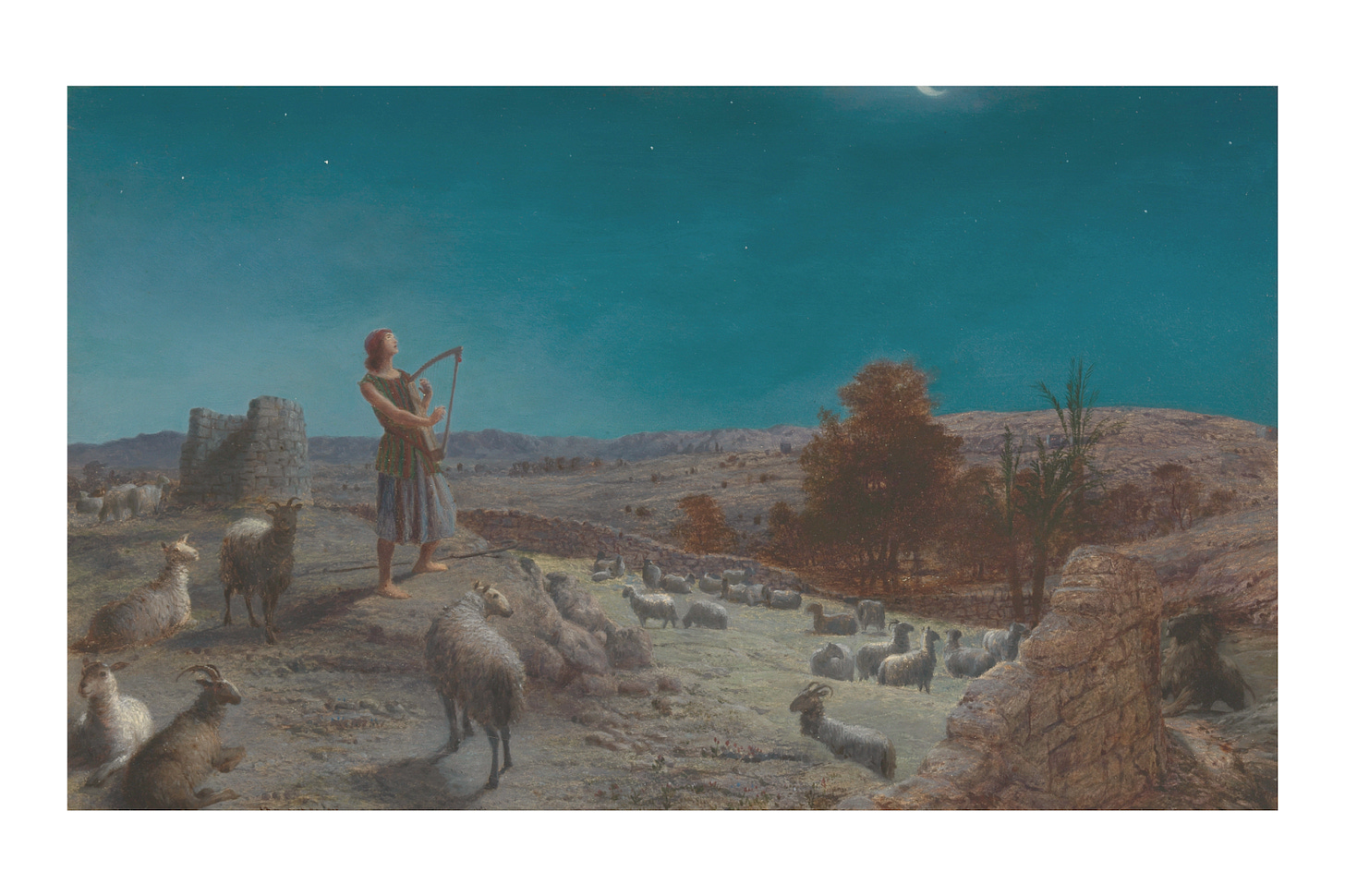

A starlit drive

As I negotiated a sharp left curve on the top of what seemed like a small plateau, I saw my headlights flicker. I was just registering in some desultory way that this wasn't a good sign when suddenly they cut out altogether. The road in front of me abruptly disappeared, and the side of the road on the opposite side of the bend loomed very large before I pulled over to the verge and stopped the car. I tried switching the lights off and back on again. (I found this technique worked well with computers in those days, which was—who am I kidding?—is the limit of my skills when it comes to car electrics. Or any other part of a car, for that matter.)

I paused to review the nature of my predicament.

I was in thinly populated countryside at night, unaware of what was ahead of me or how far I still needed to drive to get to the coast. The only light came from the stars, and I could barely see the sides of the road. I had no means of contacting anyone I knew.

Here, in this nameless hill country, kept company by starlight on Nochebuena, I considered my options. I could turn back; at least I knew that bit of the road now, and I might find help in Palestina.

Or I could stay and wait for help. But I’d seen no other vehicles. I looked about me again. The road was deserted.

A third option was to press on, in the hope of finding a village and some help along the way. This was the craziest option, but sometimes the craziest option is also the easiest. All I needed to do was keep going. But then again, driving blind along an unfamiliar road seemed like a genuinely stupid thing to do.

Thinking all this, I leant back against the worn grey bodywork of the Land Rover and gazed up at the stars, which were bright by now. One, in particular, shone brighter than the others. I looked at it and wondered what my friends back in Guayaquil would say now. More to the point, what would they do? Most were devout Catholics, though in a highly selective way (the Church’s teachings and rituals were a kind of self-service menu from which they chose the bits they liked). I figured they’d probably pray to the Virgin Mary at this point.

I’m not religious, and I never pray. I didn’t pray then, but as the thought of driving in the night (without lights) came into my mind, the light of the star seemed to grow a little brighter. I could feel my spirits begin to rise. It made no sense to me then and makes no sense to me now, but somehow, I felt protected.

Looking back, I still marvel at my lack of panic in this moment. Ok, the stars are bright enough to see by, I thought. I’ll be ok if I keep my pace to a crawl.

So that’s what I did. For the next half an hour, I drove through the featureless equatorial night at a walking pace, guided by starlight, hoping I’d find help before I ran out of fuel. Scanning the darkness, with my pupils straining to open further to let in every stray particle of light, I felt strangely alert. In the blankness of night, the Land Rover felt immense, and as the engine roared along in first gear, it might have resembled, to any observer, a sightless grey dragon slouching towards an unseeable horizon.

A weary traveller seeking help on Christmas Eve

As the constellations slowly shifted overhead, a dark form became visible. Some kind of building. And then a light. Was this a village? It wasn’t late, and I knew everyone would eat much later than usual on Nochebuena. Perhaps I could find someone to help me?

What I came upon was better than a village; it was a ramshackle taller, a multi-purpose workshop that perhaps served the local farming community. (I didn’t know, and I didn’t care!) I called out, and a man appeared, naturally suspicious of a foreigner driving in the dark with no lights on his car. He was short, somewhere in his forties or so, and he wore the greasy overalls that are the uniform of mechanics everywhere. In his hand, he held a large spanner (which is what we call a wrench in Britain). He appraised me for a second before speaking.

“Qué quiere?” (“What do you want?”) he asked gruffly. I greeted him as politely as I could. “Discuple la molestia señor” (“Sorry for the bother, sir”). Then I explained the problem. Could he help? He lifted the bonnet/hood, which probably weighed as much as I did, with a practised sweep of his hand and peered inside with the help of a torch (flashlight). He then looked at me with a mixture of amusement, incredulity, and condescension on his face. And then said yes, he could.

Within about five minutes, after a bit of to-iing and fro-ing, and a moment of near immersion as he dived into those mysterious depths normally hidden under the bonnet, he’d replaced a fuse (these things will always remain a holy mystery to me) and told me I was good to go. Relieved and slightly embarrassed in my Englishness to have bothered him with such a trifle, I thanked the mechanic and asked him how much he wanted for his help.

“Lo que tenga a bien darme," he told me (“Whatever you see fit to give me”). I gave him 500 sucres (less than a dollar). He seemed satisfied and said goodbye. I think he even wished me “Feliz Navidad”.

I drove off as briskly as my lumbering vehicle would allow, its headlights flaring out into the night. From there, my drive was smooth enough. Soon I reached Portoviejo, the provincial capital, and from there it was a straight drive down to Manta, one of Ecuador’s busiest ports.

By now, the night air was pleasantly cool but moist, and there was a scent of the breeze from the nearby ocean. While replacing the fuse in my car, the mechanic had even fixed the cassette player, and I celebrated my arrival in the well-lit city by playing Tracy Chapman’s Fast Car.

Such had been the precision of my travel planning, I hadn’t booked a hotel. But I soon found a place to stay. There clearly weren’t many travellers out and about on Nochebuena, and there were vacancies in a place just across from the beach.

Within minutes, I was sitting in the hotel dining room, enjoying a Cena de Nochebuena, my Christmas Eve dinner. If I’m honest, it was a rather unappetising meal of greasy goose, overcooked plantains, and oily rice. But I didn’t care much. It tasted just fine to me. I thought of my Christmases on the farm as a boy, when I’d feel ready for a vast festive dinner after a couple of hours of work feeding the heifers or helping to clean out the covered yard where the cows wintered. I felt I’d earned this supper, too. Without ever imagining that survival was at stake, I’d survived my trip to the coast. And without ever knowing where I wanted to be, I’d arrived.

I looked up as I put down my knife and fork, pushed away the plate, and leant back in the simple rattan chair. Through the dining room window, I could see the incessant Pacific surf visible in the glow coming from the hotel.

Further out to sea, there were the lights of small fishing boats bobbing in the waves under the star-lit sky. It would be a calm and relaxing place to spend a few days. Nobody was expecting me to be anywhere else. I could do as I please and unwind in the gentle ocean breeze, reading the Ecuadorian novels I’d saved for my holidays, enjoying the supreme comfort of a hammock on the beach, with only a cuba libre for company.

But I knew that the next morning I’d check out early and head back to Guayaquil via the main road. I’d had enough of being alone this Christmas.

❤️ Happy holidays to all readers of the English Republic of Letters! I truly appreciate your being here. ❤️

Note:

was a developmental editor on this essay.From Journey of the Magi by TS Eliot

I’ve given you a map to plot the journey I made, just above this footnote

A great adventure! And Amanda is everywhere good writing is found!

Just marvellous. Reading your story, I felt like I was sitting next to you in that car. Great musical choices as well. Thanks, Jeffrey, and Merry Christmas!