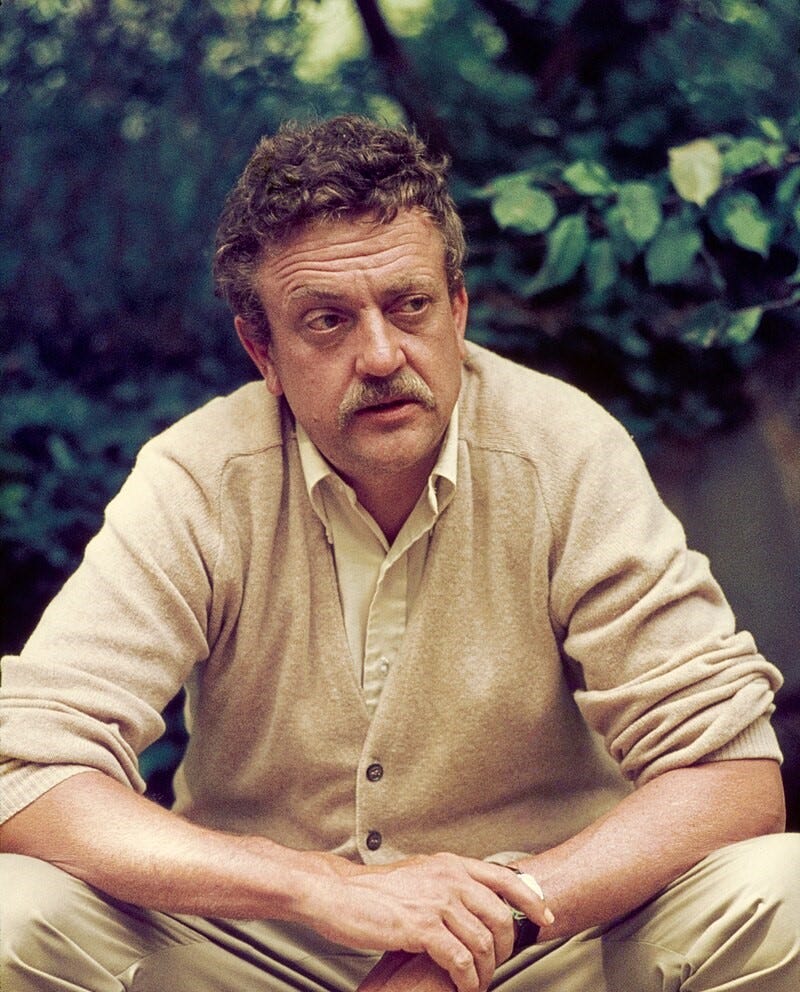

When I arrived blinking in the dim light of Substack, wondering which way is up, Gabe Hudson’s well-known generosity found its way to me. In my first post written after one week here, I mentioned how important his kindness had been. Now, I join the many others who are mourning his death and who are also bringing together some way to honour him. Not long after joining, I told Gabe that I had a Kurt Vonnegut tale to tell, and he was keen to know more, even though I was nobody to him. (But of course, everybody was somebody to Gabe, as you can see in these other tributes to him.)1 I was slowly working on this essay below and had hoped to share the final version with him before I published it. But that day never came.

So, in honour of Gabe and Kurt Vonnegut Radio, his brilliant podcast, I decided to work on my story and publish it now as a humble and heartfelt tribute to Gabe.

Sometime in my second year at Oxford, I had the honour to become head of the University Literary Society (no one else wanted to do it, which you can read more about in the footnotes)2. Under the auspices of this august body3 , well-known novelists were invited to give a brief talk about their work.

We had writers such as David Lodge, Salman Rushdie, and a certain Kurt Vonnegut. The latter’s visit was put together by a friendly member of the university, and everything was set up through his UK publisher. The lecture hall was booked, the posters went out, and I drafted a few handwritten speaking notes as the person hosting the event. I’d done this before (twice, anyway). I felt I was getting the hang of hosting what were fairly sedate literary events.

The big night came. Accustomed to walking into half-empty lecture rooms, I was stunned to see the venue was packed out. There was a real buzz in the room. The great man arrived with his UK publishers, who, in their flowing cashmere overcoats, strode to their place at the door. Their writer politely introduced himself to me and strolled towards the stage, at which point the buzz became—well, whatever buzzes become when they get very loud.

My informants told me he had a good following. What they hadn’t made clear was that Mr Vonnegut held literary rockstar status. It seemed he had thousands of devoted fans in the city who realised this was the only chance they might ever get to see their hero in the flesh. They weren’t going to miss it.

Fortunately, an unpaid warm-up act had been procured in the form of a youthful, charismatic member of the university English Department. The idea was that I’d welcome everyone, then introduce the lecturer, who’d say some suitably upbeat things about Vonnegut to get everyone in the mood. Which is what happened.

I said how pleased I was to see everyone, how wonderful it was to have Mr Vonnegut here (palpable excitement in the hall when his name was uttered), and so on. It all started well, even if the lecturer went on a little too long for the liking of the crowd, who were only here to listen to one person.

And then the moment came.

"I'm delighted to ask Mr Vonnegut to give his lecture” (this was Oxford in the 1980s, so we said “Mr”).

The room erupted into huge applause. The great man cleared his throat.

For the next 40 minutes, he had his audience spellbound. They didn't just devour every word. They hoovered up the speech gesture by gesture, phoneme by phoneme, and dramatic pause by dramatic pause. Mr Vonnegut was relaxed, charming, full of wry humour, and seemingly improvising (he’d probably done this a thousand times before). I was mesmerised. And I wasn’t the only one. When he read a passage from “‘Breakfast of Champions," you could see a long-suppressed excitement on the faces in the audience. For them, years of solitary, rapturous reading of his books came together in that one moment. They were in heaven.

Then came the message from the publishers. It was time to put a full stop to the talk and leave for dinner.

I could, perhaps, have resisted. Surely dinner could have waited? Everyone was having such a great time, even the great man himself. Perhaps especially him—there was a smile in his eyes as he delivered his one-liners about writing. But a look at the faces of the publishers told me everything. He was their author; they’d paid for him to be here, and this callow student had no say in the matter. I needed to wrap things up.

How do you tell Kurt Vonnegut to wrap up?

There are moments in life when you are faced with a great challenge, think things are just all too much, and yet you find a way to overcome the obstacles and impress yourself and everyone else with how well you dealt with the situation. These are the moments in which you grow.

But this wasn’t one of them.

My heart pounding and my palms sweaty, I somehow edged towards the stage. Mr Vonnegut kept talking, but I could feel a thousand pairs of eyes upon me. His fans suspected the worst. This slouching Nobody wanted to take their hero from them. I edged further forward. Mr Vonnegut stopped speaking and looked at me blankly. Before he could say anything, I blurted—no other verb will do—I blurted out:

“I’mverysorryMrVonnegutbutwereallymustbringsthiseveningtoaclose”.

The great man glanced at the publishers, who looked back, shrugging their expensively-clad shoulders apologetically, and communicated a clear message: “Hey, look, we wanted to carry on, but these dumb organisers had other ideas, WTF. However, now that you’ve stopped, let’s leave.” So smooth, so much meaning in a practised glance and gesture. Sure, blame it on the kid.

I felt alone. My only hope for a lifeline was Mr Vonnegut himself.

This is probably the moment to disclose that, at that time, I wasn’t just unaware of Mr. Vonnegut’s following. I'd actually never read any of his works. Ok, full disclosure: I'd barely heard of him before the event was organised. What can I say? I was from the depths of the English countryside. It was 1982, and in Devon, we'd only just discovered Punk... So there I was, on false pretences, suffering not so much from imposter syndrome as from a full-scale imposter infestation.

I glanced despairingly at the author. Could he tell I didn't know my “Breakfast of Champions” from my “Slaughterhouse-Fives”? What would he say?

“Ok, folks,” he said. “Looks like we’re being told to stop. It’s been great talking to you this evening.” I felt a gushing teenage gratitude for him being so neutral toward me. Who knows, perhaps he’d had enough anyway?

He paused before wrapping up. By this time, audible murmurs of disapproval were bouncing off the walls of the hall and converging on my person. A thousand angry eyes were trained on me. But at least I’d be thrown a lifeline in the form of the maestro's momentary (and pitying?) indulgence of my presence. Could I grab it and escape with some dignity, even panache, via some witty remark? Or could I at least show some composure?

“I’mreallysorrytobeinterruptingyouMrVonnegut,” I spluttered in his general direction, scarcely audible.

The lifeline had slipped through my hands.

One of my Spanish friends used to say “¡Trágame, tierra!” at moments of monumental embarrassment. “Earth, swallow me.” But I was a shy young man. So this was more galactic in scale. Perhaps the nearest black hole could kindly intervene to get me out of there?

It could not.

So while Mr Vonnegut performed his peroration, and then duly received the wild applause of his grateful fans, I was reduced to the status of a kind of ancillary literary antimatter. Now, my guess is that many of the fans were also devoted to Star Trek. So they had their mental phasers trained on me and not set to stun. I looked around desperately for the transporter room. But there was no shimmering beam to take me to safety, just the glowing wrath of the frustrated and enraged fans. Meanwhile, Mr Vonnegut padded out of the lecture theatre with graceful calm. He even thanked me (I think) before he was whisked away in a whirl of camel cashmere by the smiling publishers. They’d got their man back. And I was left at the mercy of the mob.

Except that they were no mob. Mr Vonnegut's fans shared, of course, his basic decency. The moment of frustration passed in an instant, and most of them left the hall high on the joy of having seen and heard their icon. One or two even sent a nod of gratitude in my direction. But mostly, I was ignored. The crowd soon dispersed, leaving the hall almost empty. Deciding to cede the field to the tender care of the gathering university cleaners, I made my exit unobserved. I opened the glass door of the theatre, turned a sharp left into the blank Oxford night, and headed home.

Epilogue:

Of course, it wasn’t long before I started reading Vonnegut’s novels, and when I finally went to do postgraduate work at a university that actually believed in teaching literature written within living memory, I even took “Slaughterhouse-Five” as a set text. I then experienced the deep humanity of his writing. And I think it was that golden thread of human decency that connected him and Gabe. I saw that in the way that Gabe treated me as a newcomer on Substack. I saw it in his interactions with others. I heard it in his interviews. It’s a rare gift.

Note:

was a developmental editor on this essay.Here are a few tributes to Gabe you might appreciate reading: “Remembering Gabe Hudson,” by

; “Just Say the Word and I’ll Bring My Whole Heart…” by the team at McSweeney’s; and this reflection, “Whatever We Were to Each Other” from .As a quick cultural note on my time at Oxford: when I attended, not everyone was leadership obsessed. As much energy went into drama as it did into politics at that time (the two may seem connected, but I’m not sure). And certainly, the people who wanted to leverage their privilege to "lead" the country wouldn't have touched the literary or poetry society with a barge pole. They'd have joined the Oxford Union or written for university newspapers.

Not to be confused, of course, with the Oxford University Poetry Society (which I also ran at one stage, but we’ll save that little gem for another time).

Gorgeous account. Kurt was from Indianapolis, where I was born in 1959, and where the language was like, I think he said, "common speech sounds like a band saw cutting galvanized tin, and [it] employs a vocabulary as unornamental as a monkey wrench." Dead on. Our family left Indiana in the mid 1960s and move east to Maryland where I got that upbringing and then hurled back to the Midwest where a new Death awaits unless you escape it. The shitshow is all around. Pick your playground, Mr. Vonnegut would say, and I feel him present as we speak.

this was beautiful