Krapp's Last Tape

On replaying the past

Over the last 15 years, I’ve kept a rough kind of diary, dotted with the usual lists of books read, interesting quotes, things that have happened to me, and inchoate thoughts on the future. Something I include in this is a review of the year, usually written in December.

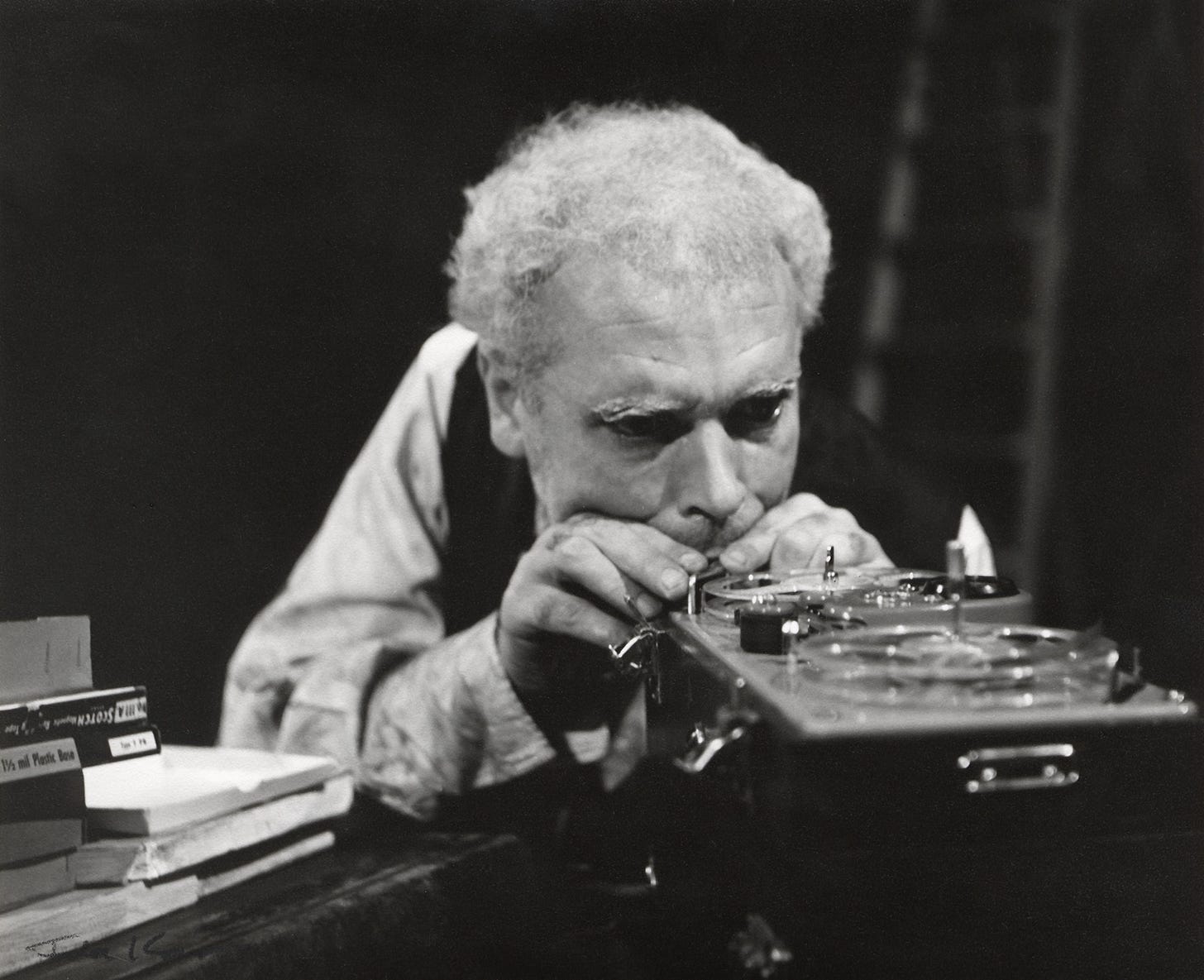

My inspiration for such a review, if inspiration’s the right word, came not from any of the many self-help articles on the topic but from a play, Krapp’s Last Tape by Samuel Beckett. In it, the eponymous hero, the only character we see in the play, listens to his own recorded diary, from tapes or spools that span many years.

“Spiritually a year of profound gloom” is one of his summaries, and this striking and beautifully balanced phrase is one of a number of Beckett’s that echo in my head on a regular basis. My own years are only occasionally gloomy, rarely profound, and never spiritual, but somehow the phrase recurs as a point of departure when I look back on the year just past.

📼📼

Beckett’s writing is often associated with gloom or despair, but my own associations with his work are more varied and include a romantic element. One reason for this is that Beckett’s writings were undoubtedly among the biggest influences on me at the impressionable age of 18 and into my early 20s.

According to one, not very acute, summary of Krapp’s Last Tape, the play “explores the solipsism, obsessions, and communication of an ageing writer.” To be honest, that sounds more of a description of me and the English Republic of Letters than the play.

I find Krapp’s Last Tape a beautifully lyrical piece, centred on moments of epiphany and a failed love affair, like so many of the best stories. And when I first heard the play performed by the incomparable Patrick Magee,1 for whose voice it was written, I was at the beginning of a story that would end with that final departure from an island by ferry that I wrote about in May.

Krapp’s Last Tape became for me the love poem that captured the almost meteorological inscrutability and beauty of a first love.2

I’d recently got to know M, as I’ll continue to call her, and those early days of the relationship are forever linked in my mind to Beckett’s play. One of Krapp’s recordings covers a moment when his younger self describes a moment of bliss on a punt on a lake with his beloved:

We lay there without moving but under us all moved and moved us, gently up and down and from side to side.3

Typically for Beckett, the sentence has a wonderful rhythm to it. And performed in Magee’s voice, it is little short of magical. It certainly was for my 20-year-old self.

📼📼

During the winter of 1982, I probably spent too much time by myself and almost certainly read more Beckett than was altogether good for me. The solitude of those winter days and evenings was punctuated, however, by an afternoon walk with M.

We met up in London and went to Hampstead Heath, near where she was then living. We walked its meandering paths, climbed the low, wooded hill, and enjoyed the faltering sunshine of a bright winter’s day in London. We visited Kenwood House, an 18th-century villa that is open to the public and boasts an outstanding art collection. I was just discovering the music of Handel and Rameau at the time, and it was as if the art and architecture of the place conjured the harmonies of their music into my mind as I wandered its halls with M.

After we left Kenwood House and headed south across the park, we found ourselves at Parliament Hill and saw the lights of the city beginning to flicker below us. We stopped. It was growing cold, but our warm coats protected us, and I don’t remember feeling the chill of the early evening.

Time had slowed down. Geography was simplified into the shimmering city, the dark wooded hills, and M.

I’ve no idea how long we stood there, staring at the view, dizzy with unspoken meaning.

Past midnight. Never knew such silence. The earth might be uninhabited.

These words of Krapp’s still replay in my memory of that time.

But neither of us spoke, and our moment passed.

📼📼

Just been listening to that stupid bastard I took myself for thirty years ago,

says Krapp, after listening to the recording of his beautiful description of the scene in the boat.

I hope I’m less harsh on myself than Krapp as I look back now. Perhaps M even looks back with charity on that day.

I asked her to look at me, and after a moment, after a moment, she did. But the eyes just slits because of the glare.

Love occurs perhaps when the radical unknowability of another person becomes a holy mystery. M could have had no more idea of what was going on in my head than I of hers. All we had were fleeting hints of smiles or gestures, like the lights that shimmered intermittently from the city below.

The city is at its most beguiling when seen in this way. But the twinkling lights are not the city we see in the full glare of day.

📼📼

As far as I know, M remains on the island that I left in 1988. But I followed the trade winds to the Americas, then the ocean currents to East Asia, then went overland along the spice road to Europe, West Asia, and North Africa.

The same forces that were gently buffeting the waters under Krapp’s punt have oscillated throughout my life and brought me here, to a very different island in a different ocean altogether.

Perhaps my best years are gone

says Krapp in one of his recordings.

But I wouldn’t want them back. Not with the fire in me now… No, I wouldn't want them back.

The play premiered at the Royal Court Theatre in 1958. A recording of Magee’s 1972 filmed performance is here.

Of course, there’s a lot of other things going on in the play

All block quotes in the text are from the play as recorded in 1972.

Thank you so much for your kind words, Yi! I think most cities look better at night. That's certainly the case with where I am now, Tokyo.

I'm not sure there's an easy entry point to Beckett. For the plays, seeing a live performance of Waiting for Godot would be my suggestion. For the fiction, perhaps Murphy or Molloy. The latter is widely considered his best sustained prose work.

The love story that you write here emerges for me as well from the play. I am struck in this beautifully vulnerable essay by the exchange that occurs when a reader expresses how the words of another resonate. That is the ultimate closing of the round. I suspect, Jeffrey, that Beckett would have been honored to read this essay about this play that he worked on for such a long time.