There’s a striking full-length of Henri Matisse (1869–1954) in this exhibition at Tokyo’s National Art Centre, in which the artist, about to enter a door (to a chapel) and looking a lot like Orson Welles or Burl Ives from the film version of Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, is turned towards the photographer—to the viewer—with a look that is neither aggressive nor benign, but slightly quizzical.

Que voulez-vous? He might almost be saying, What do you want?

*

I’m here to ponder and solve a personal mystery: Why is it that the work of Matisse, considered a 20th-century master, has never really moved me?

I thought perhaps it was because I’ve never seen a lot of his work together. Now I had the chance to change that.

What follow are my notes from this exhibition, as I tried to pierce through into a greater appreciation or understanding of his work. 1

*

We can quickly skip over Matisse's early still-life paintings, which didn’t seem particularly noteworthy - though I read in passing that Eugène Delacroix appears to have influenced him. You feel that curators pad their exhibitions with this kind of thing for completeness, rather like an editor of a major edition of a poet’s work includes mostly uninteresting "juvenilia.”

But as soon as you get to “Madame Matisse" (1905), the colours of what became known as “fauvism” begin to startle the eye and attract your attention, and the strong, bold lines retain it. Soon after, I came across the sumptuous reclining figure in “The Odalisque with a Red Box” (1927) and other portraits and paintings of the same period, and I found myself dazzled by them. For the first time, Matisse was interesting to me. His work was coming alive.

The charm was perhaps reduced, though, when I recognised the term “odalisque"—in Western art it means harem concubine—and realised the less-than-appealing orientalism at work in his painting during this period. It was even more evident in works such as “Arabesque” from 1924. More of Delacroix’s influence?

*

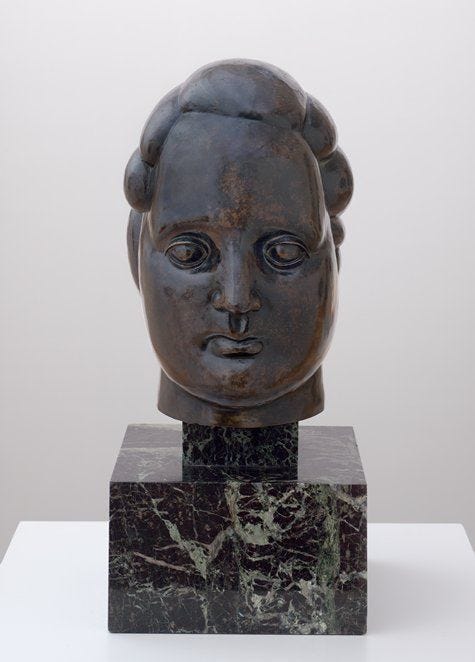

Next, I was able to admire some fine sculptures, which, frankly, I hadn’t expected to see. There was a fine reclining figure and also “Jeanette III” (1911), which was very severe, very French, but also looked a bit like Margaret Thatcher, I thought (though less so in this photo). And I enjoyed the comparison between this and “Henriette II” (1927) and its depiction of a fuller face, one of greater vulnerability.

*

Towards the end of the war and after a severe illness, Matisse moved to a small village called Vence. In the work he created here, I detected more introspection. Here, he experimented with a new method of composing his image by laying out the colour in flat planes. It made me think of Samuel Beckett also refining his technique in wartime France, moving from the knockabout Murphy (1938) to the interiority of Watt (written in 1945 and published in 1953) in another part of France. “Teacher at the Yellow Table” (1944) is a particularly lovely work from this time (curiously, there’s no attempt at fingers or even hands in this painting).

And there’s the beautiful, slightly dizzying painting of “The Racaille Chair,” (1946), where the chair appears to force its way beyond the frame.

The examples of still life in this period seem to have had vastly more energy and originality than the early works. I especially enjoyed “Still Life with Pomegranates” (1947).

After some beautiful ballet costumes for Balanchine’s Le Chant du Rossignol, it was time for the sketches for the Barnes murals—sumptuous dancing figures—displayed via a projector on the museum wall.

These lovely figures took me back to Poussin, to the Borghese vase that inspired so much Renaissance painting of dancing figures. I felt deep lines into the past anchoring this daring and bold work.

*

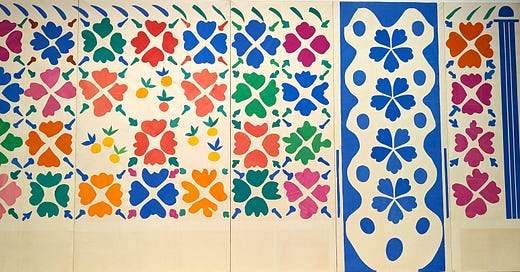

Then came the cut-outs. Some of the figures Matisse made using this technique carry on the sense of dance and movement of his early work.

And the monumental “Flowers and Fruits” (1952–3) I found striking and impressive (see image at the top of the page).

But frankly, after a few examples, the initial sense of fun begins to dissipate and I begin to lose interest in the cut-outs. I don’t know if this is an artistic dead end; according to some, they are now the “most-celebrated of all of Matisse’s artworks. But I found my attention beginning to wane quite quickly at this point.

*

A feature of this show is the ambitious final section depicting the artist's designs for “The Chapel of the Rosary, Vence” (1950-52). This he described as the culmination of his career:

“I started with the secular and now in the evening of my life, I naturally end with the divine.

Henri Matisse, quoted by Monsignor Rémond, in L’Art sacré, July-August 1951”

Certainly, the designs for the glass windows and the priests’ garments, including items of clothing I hadn’t seen named before (chasuble, maniple), are colourful and enjoyable.

The mock-up of the chapel captured perhaps some of the pathos of the setting; the artist said that the design was supposed to be at its most atmospheric on a winter morning, which I can believe.

As for the spiritual aspect, that's his story to tell. But I couldn’t see this as an artistic culmination. And I couldn't help contrasting this work with the energy of a Messiaen mass or even Poulenc’s religiously inspired music, finding Matisse lacking in passion by comparison. Perhaps I’m wrong, but I felt this was more accommodation or resignation than celebration.

*

Que voulez-vous, I imagine the photo/ghost repeating.

And I think about that question. What do I want—a relatively ignorant observer, picking apart his work like an untrained surgeon?

Why do I come here in solemn procession to bestow my gaze on these highly stylised objects in this curiously church-like setting?

Que voulez-vous?

I guess I come on trust—trust in the curators that they can help elucidate the mystery of Matisse for me. I certainly want to learn from them. On the other hand, I want to resist their narrative. I want to find my own pattern. I want to find artworks that will leap out at me and tell me their own stories, so that I can incorporate them into mine.

*

And indeed, I came away feeling that at least I understood Matisse’s work a lot better. I was hugely impressed by much of the art of his middle period, especially the colourful portraits and later examples of still life. Here I saw an artist fascinating us with the way he worked with light, shape, and colour. These are the works I want to go back and see again.

“Art is not what you see, but what you make others see,” said Edgar Degas. Matisse was making me see the world through new colours.

And yet…

One critic has called Matisse, comparing him unfavourably to artists such as Picasso, “a little too bourgeois and decorative.” I don’t know if I would endorse that view, but I found little that moved me in the cut-outs, the vestments, or the chapel windows.

*

I imagine the figure in the photo responding with a gallic shrug.

Comme vous voulez, he seems to say. As you wish. Now leave in peace. Leave me in peace.

And in my mind, I see the artist turning away to enter the chapel, shuffling with difficulty over to the spartan wooden pews, where he sits awkwardly before composing himself into silent prayer as the priest slowly makes his way to the altar. A choir begins to sing as the light fades on a dull winter afternoon. The lights of the chapel catch the bright designs of the windows and cast yellow and blue patterns of light outside.

The exhibition goers respectfully look away from the ceremony, and then we move slowly on, as we must, shepherded by museum guards rather than by priests. Gradually losing our reverence, we head towards the gift shop and then on through the museum’s green cathedral of glass before we find ourselves once more out in the uncaring light of spring.

The exhibition only allowed photos of the second half, so my own photos are taken from the later works.

Thank you, Kate, for your kind words and for identifying these key themes. An exhibition like this is a multiparty conversation, isn't it, with artists, curators and the viewers all having their say. It's a complex event which throws up as many questions as it settles.

What an interesting, brave post. You are reckoning with the master, interrogating yourself, asking what you have missed. I'm not surprised the cutouts didn't move you. They are decorative but not profound. His greatest work reaches toward joy through suffering. I have looked at Matisse in many museums but the Barnes, in Philadelphia, is home to "Le Bonheur de Vivre" in which the artist's joy seems transcendently anchored in a deep understanding of sadness and loss. Francoise Gilot, in her memoir LIFE WITH PICASSO, has fascinating insights into Matisse and his rivalry with Picasso. Matisse once told Picasso, "We must talk to each other as much as we can. When one of us dies, there will be some things the other will never be able to talk of with anyone else."