In November 2021, I received an urgent and painful personal imperative. I decided to read or reread all 15 novels written by Charles Dickens1. You may be thinking, "hey, that's a ton of books to haul around the world," and you would be right! This is where technology comes to my aid, enabling me to store all these books on my ageing Kindle and thus avoid shipping a small library from port to port (I was in Hong Kong when this task landed in my lap).

As anyone who's ever read Dickens knows, in reading his work, I would encounter a whole galaxy of characters whose company I enjoyed a lot (with a few exceptions). One of the most endearing to me—and Dickens' personal favourite of all his characters—is Mr Dick from David Copperfield.

Mr Dick is a kind man who, perhaps because of his simple wisdom, reminds me of Uncle Toby from Tristram Shandy. Although Mr Dick is a man of many abilities and quirks, his all-consuming passion with the life and especially the death of King Charles I is perhaps what strikes us as his most remarkable feature when we first meet him.

So earlier this year, I wrote about Mr Dick in a blog post for my website. I’d long wanted to blog about literature and my life travelling around the world, and at that stage, it hadn’t occurred to me to write on Substack. To cut a short story even shorter, my website did not attract much attention, and I seemed to spend a lot of time just tinkering with the site itself.

Fast forward to this autumn. I’m now on Substack, and I thought that I could engage in a bit of self-plagiarism, as

calls it, and reuse an article I’d already written for that website for the English Republic of Letters (which is also the name of my website). However, as I read through what I’d written just six months ago, I became increasingly dismayed. “This just isn’t good enough,” I thought. “It isn’t focused, the writing lacks crispness, and the main themes, such as they are, aren’t developed far enough.” My idea of just pasting the thing into the Substack editor and sending it out to you just didn’t seem right.You, including the many new readers of this newsletter, who I am so pleased to see here, deserve better, I thought.

What had happened? Had my writing got so much better in those few months that I was now operating at a wholly new level? Well, not really. Had my critical faculties kicked in, fitfully dormant in the years since my training in literature? Possibly.

But as I reflected, I realised that what was really going on was that my last two months reading hundreds of essays on Substack had made me greedy for the good stuff and less patient with the not-so-good. Fortunately, there’s a lot of really good essay writing on Substack. It was the high quality of the writers I most liked here which made me want to up my game.

That, I further reflected, is the best reason I can think of for being on Substack. I feel grateful for that.

But what to do about Mr Dick?

As it happens, one of the very best essay writers on Substack,

- I’m in awe of her talent - said in Notes the other day: “The practice of simply retyping your drafts from scratch instead of trying to edit a virtual document is seriously, woefully underrated”. And recently, Sarah Fay from mentioned in her brilliant masterclass on the essay that one writer - from memory, it was Anton Chekhov - used to burn first drafts and rewrite from memory, in the belief that he’d remember all the important stuff and would write it better a second time.So, rather late in the day, I thought I’d give it a go. But rather than try to rewrite the essay I’d written, I thought I’d try to (re)write the text I should have written, and that was probably somewhere in my head in an early draft.

I’d actually come up with a couple of very different thoughts about Mr Dick. One was related to his role as a writer. He is constantly writing his memoir - ‘Memorial’ is his word for it - but never getting very far. He would experience disturbing thoughts about the beheading of Charles I at some point in his writing, which would prevent him from continuing. He’d then start all over again.

We’d perhaps call these “intrusive thoughts” these days. And the conjunction of the names Charles and Dick suggests there’s a lot going on under the surface with the name of the author himself, and some of it has been explored here.

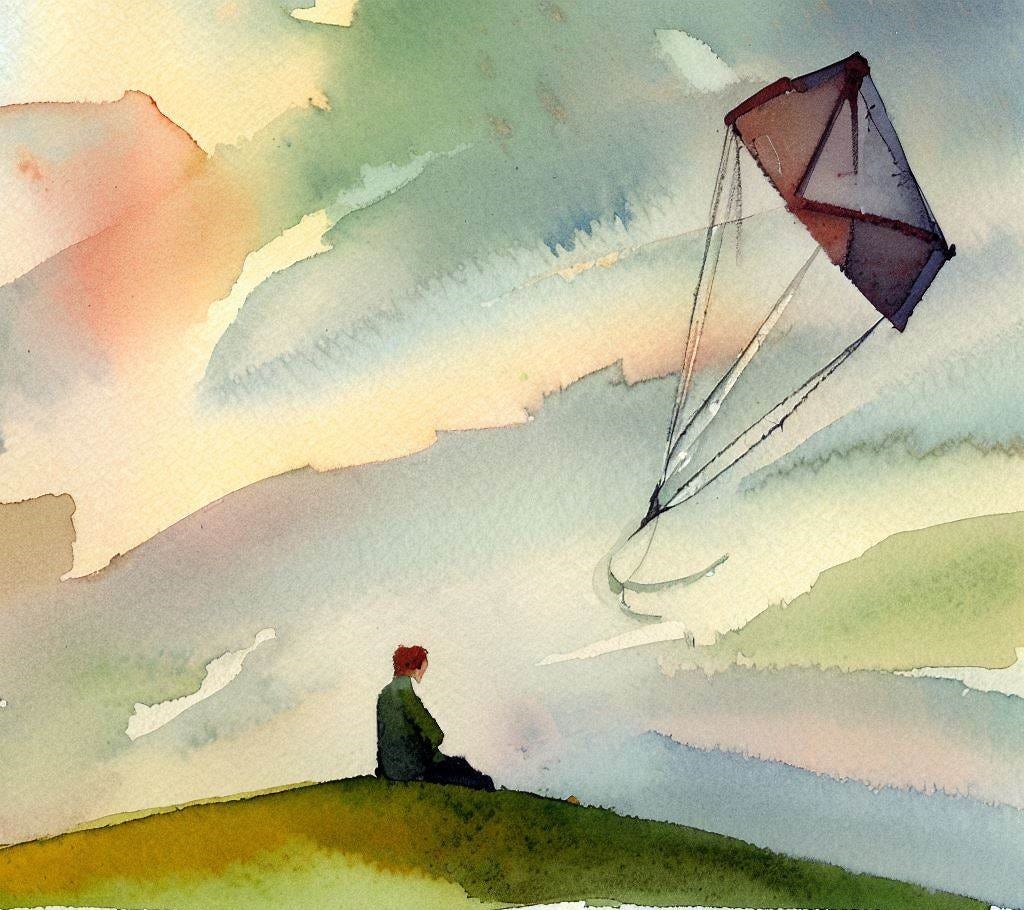

But the detail that really caught my attention was what Mr Dick did with his abandoned manuscripts. Rather than burning them, as Chekhov did (if it was Chekhov), Mr Dick glued the papers together and made a kite out of them. He made his words fly.

This, I thought, was quite an inspiring image. But Dickens goes further and had Mr Dick imagining the flying kite “disseminating the statements pasted on it”. To the 19th-century reader, this may have simply been one of Mr Dickens’ flights of fancy. To us - or to me at least - it feels like some kind of embryonic World Wide Web. I thought of Mr Dick’s words floating down upon the southern English hills, enchanting readers in the towns and villages with their delightful observations upon 19th-century life. And it was interesting to reflect, as I now drafted my humble newsletter designed for instant dissemination via subscription, that Mr Dickens, who wrote to his public via a subscription model, was an early master of mass dissemination.

The other thing that fascinated me about Mr Dick was the contrast between him as a vulnerable adult, under the watchful care of Betsey Trotwood, when we first encounter him and his role as some kind of inspiring seraph later in the book.

Early in the novel, we see Mr Dick finding solace from his troubled mind by flying his kite:

“I used to fancy, as I sat by him of an evening, on a green slope, and saw him watch the kite high in the quiet air, that it lifted his mind out of its confusion, and bore it (such was my boyish thought) into the skies. As he wound the string in and it came lower and lower down out of the beautiful light, until it fluttered to the ground, and lay there like a dead thing, he seemed to wake gradually out of a dream; and I remember to have seen him take it up, and look about him in a lost way, as if they had both come down together, so that I pitied him with all my heart.”

The narrator, David, pities Mr Dick, who can only truly escape the confusion of the world and his mind when he is airborne - or rather, when his kite is. When the kite hits the ground, so does Mr Dick, who’s rather like a angel fallen from heaven.

But as the novel moves towards its conclusion, we see another side of Mr Dick emerge. Dr Strong, an older, intellectual, and other-worldly friend of David’s, and his much younger wife, Annie, suffer a marital crisis caused by the latter’s selfish, attractive, materialistic cousin, Jack. Dr Strong believes there’s some kind of inappropriate relationship between the cousins, though he is too honourable to accuse her of misconduct. As this painful situation comes to an excruciating moment of crisis, Mr Dick is the one who’s on hand to offer support:

“Mr Dick softly raised her; and she stood, when she began to speak, leaning on him, and looking down upon her husband - from whom she never turned her eyes”.

The moment passes, the crisis is resolved, and Mr Dick becomes the invaluable confidant of both of the Strongs:

‘When I think of him, with his impenetrably wise face, walking up and down with the Doctor, delighted to be battered by the hard words in the Dictionary; when I think of him carrying huge watering-pots after Annie; kneeling down, in very paws of gloves, at patient microscopic work among the little leaves; expressing as no philosopher could have expressed, in everything he did, a delicate desire to be her friend; showering sympathy, trustfulness, and affection, out of every hole in the watering-pot; when I think of him never wandering in that better mind of his to which unhappiness addressed itself, never bringing the unfortunate King Charles into the garden, never wavering in his grateful service, never diverted from his knowledge that there was something wrong, or from his wish to set it right- I really feel almost ashamed of having known that he was not quite in his wits, taking account of the utmost I have done with mine.’

It’s a beautiful passage, full of sonorous “-ing” verb forms that conjure an almost Edenic serenity in the garden. King Charles has not gone away, but isn’t let in. The previously weak Mr Dick is able to help the Strongs because he possesses an empathy that few could match. We might even call it his superpower. The writing creates a sense of harmony that allows us to experience Mr Dick’s acute mental confusions in fruitful balance with his special powers of human sympathy. And for the rest of the novel, he goes on to play an almost heroic part in David’s life.

Dickens, the successful novelist, presents the failed memoirist as a healer and shows the vulnerable, confused man as a rock to cling to at a moment of crisis.

No, the memoir won’t get written. But we don’t experience this as a failure2. Mr Dick’s vocation turns out to be friendship, rather than writing. As Mr Dick’s flights of fancy come to settle in the Strongs’ garden, we see Dickens at his most compassionate. It's a triumph of writing, which also hints at the delight that awaits us when we can connect with our better selves. But above all, it’s the triumph of Mr Dick, no longer a lost angel who’s descended to earth like a fallen kite but a welcome inhabitant of Eden, a skilled conductor of human harmony.

I’ll come back to this in a future post

This essay did get written. But whether it worked, I’ll leave it for you to let me know via comments. Thank you!

I'm reminded of recent newsletters by poet Maggie Smith, where she reports that she keeps all the drafts of everything just in case she wants to go back and capture something that got edited out but that held an image or turn of phrase that she wants back for some reason. When she wants to begin a new draft again she saves a new copy and leaves the old one for future reference. Though I understand the urge to burn things, I find some gentleness and compassion in her tactic. Some belief, by extension, that earlier parts of ourselves may have hit on something that we'd do well to go back and retrieve later.

I've never read Dickens, I'll confess. But I enjoyed this all the same.

We need more “skilled conductors of human harmony”