You’d half expect that an exhibition on animals in Japanese art (see poster above) would contain a rabbit hole or two for the viewer to fall down.

For me, visiting the exhibition recently, it was the quail. More specifically, it was the sight of a painting of a quail singing competition hundreds of years ago in Japan1. Quail sang, and competitively, too? Who knew?

I dug deeper into the matter. What follow are notes towards a brief (and deplorably incomplete) cultural history of quail, fragments collected as I fell deeper into that rabbit hole.

If I’m lucky, you’ll help supply some of the missing pieces…

The word quail in English seems to derive from the charming Mediaeval Latin word, quaccula, perhaps an imitation of their sound. But the ultimate derivation of the word seems uncertain.

The verb “to quail” seems not to have derived from the bird but from Middle Dutch quelen "to suffer, be ill,” or, “perhaps from obsolete quail to curdle (late 14c.), from Old French coailler, from Latin coagulare.”2

Quail is the usual plural.

A group of quail can be a flock, a covey, or a bevy.

Here’s the word for quail in various languages:

Dutch: kwartel

Japanese: ウズラ (uzura)

German: Wachtel

Spanish: codorniz

Chinese: 鹌鹑 (ān chún)

Apart from the singing competitions mentioned above, the Japanese hear the sound of the Japanese quail (a distinct sub-species) as “ゴキッチョー” or “gokicho”. This sounds like 御吉兆, which means “good luck.” Before a battle, Bushi warriors uttered this phrase, apparently. Therefore, it’s believed that warriors regarded quail as a sign of good fortune.

Quail make a variety of other sounds. For example, when regrouping, it seems they have an “assembly call” to get the covey back together:

“Assemble a covey” is a phrase I never expect to find a use for. But who knows.

“Quail are very reluctant to fly, preferring to escape by running away through the thick vegetation they live in. Despite this, they manage to fly as far as Africa and back each year.”3

“In 1537, Queen Jane Seymour, third wife of Henry VIII, then pregnant with the future King Edward VI, developed an insatiable craving for quail, and courtiers and diplomats abroad were ordered to find sufficient supplies for the Queen.”4

Quail typically live only two to three years (though they have been known to live up to six). But they make up for it with what has been bashfully called “prolific breeding abilities.” They have also been described as "amorous,” and, surprise surprise, the word quail has been used as slang for prostitute in English since the 16th century.

This is thought to be one such reference in Shakespeare: “Here's Agamemnon, an honest fellow enough, and one that loves quails.”5

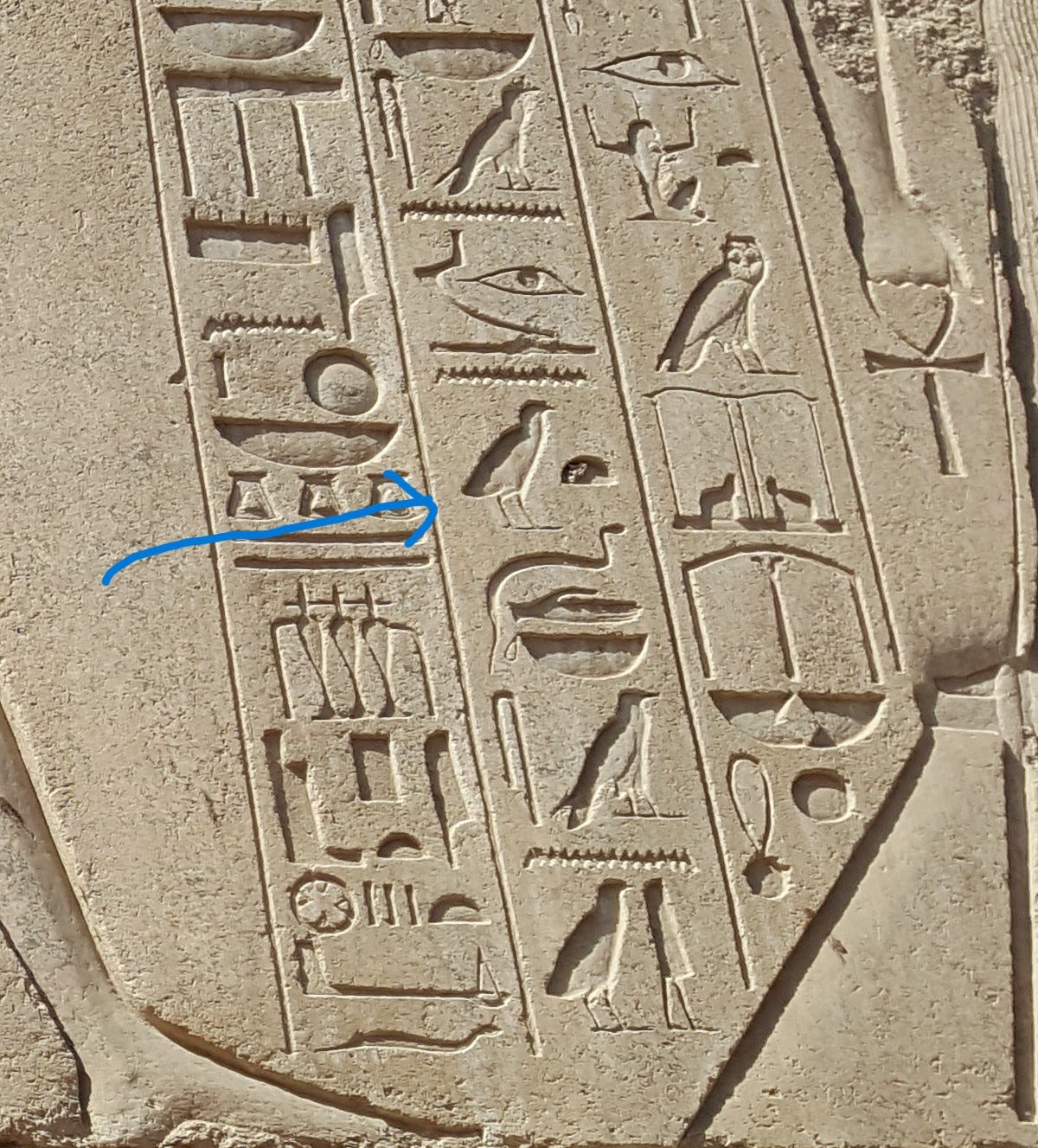

When I lived in Egypt, I visited the famous Karnak temple complex in Luxor. There, I saw, among the many beautiful images, this hieroglyph:

The quail chick was a hieroglyph and apparently represented a “w” or “u” sound.

And quail crop up in the Bible as food provided by God:

And it came to pass, that at even the quails came up, and covered the camp: and in the morning the dew lay round about the host.

Exodus 16:13, Authorised (King James) Version

This 13th-century Chinese painting depicts five quail huddled together. Quail usually denotes autumn in Chinese painting (and in Japan, they are a 季語 or kigo, a “seasonal word” for autumn in haiku).

But here, something else is going on. The Chinese word for “five quail” (五鹌鹑, wu anchun) is a homonym for “no peace” (无 安, wu an). It was painted at the time of the great Mongol expansion, which was a time of conquest and war in China. The artists and intellectuals of the south of China felt marginalised. The painting, from the south, seems to have been a veiled commentary on the difficulties of the time.

Not to waste time on nonsense. Not to be taken in by conjurors and hoodoo artists with their talk about incantations and exorcism and all the rest of it. Not to be obsessed with quail-fighting or other crazes like that.

From Meditations, by Marcus Aurelius

This makes me wonder what the modern-day equivalent of quail-fighting is.

Quail appear in some beautiful lines in English-language poetry. Here are a few examples:

And the weak spirit quickens to rebel

For the bent golden-rod and the lost sea smell

Quickens to recover

The cry of quail and the whirling plover.

TS Eliot, Ash Wednesday

What quail-like giant tail of

promises, pleiades, psalters, plane-trees…?

Jorie Graham, The Guardian Angel Of The Private Life

Deer walk upon our mountains, and the quail

Whistle about us their spontaneous cries.

Wallace Stevens, Sunday Morning

He has heard the quail and beheld the honey-bee, and sadly prepared to depart.

Walt Whitman, Salut au Monde

The first episode of “A Man in Full” on Netflix references quail hunting. There may have been more mentions in later episodes, but I gave up watching it.

Let’s finish with Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra.

Cleopatra uses “quail” as a transitive verb:

His legs bestrid the ocean: his rear'd arm

Crested the world: his voice was propertied

As all the tuned spheres, and that to friends;

But when he meant to quail and shake the orb,

He was as rattling thunder. 6

Just to be different, Antony uses “quail” as a noun:

And in our sports my better cunning faints

Under his chance: if we draw lots, he speeds;

His cocks do win the battle still of mine,

When it is all to nought; and his quails ever

Beat mine, inhoop'd, at odds. I will to Egypt:

And though I make this marriage for my peace,

I' the east my pleasure lies.7

Not shown here: photos weren’t allowed at the exhibition, and I can’t find the painting online, alas.

https://www.etymonline.com/word/quail

This is from England, and the distance to North Africa from there is 900 miles or so, at least. https://www.wildlifetrusts.org/wildlife-explorer/birds/grouse-partridges-pheasant-and-quail/quail

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Common_quail

Troilus and Cressida, Act V, Scene I. This is my least favourite of his plays.

Act V, Scene II

Act II, scene III. Could Antony & Cleopatra’s respective use of “quail” as different parts of speech become a topic of research?

You are a flaneur of poetry and art. I enjoyed the ramble , which brought back memories of cooking quail on an indoor grill. They’re too boney to justify the trouble.

A well researched piece. I love how you bring in the use of the bird in literature in various cultures. The fact that it's a word for prostitutes is total news to me. Thank you for this Jeffrey!