I don’t spend much time thinking about superheroes, but I suspect Captain America has probably never been to the のぐちや Noguchiya bakery, which is about half a mile from my flat in Tokyo.

Nor, for that matter, are any Japanese manga characters likely to drop in there for a newly baked baguette or that popular Japanese classic, カレーパン “Karē pan” (curry bread).

But on those mornings when I enter it on my way back from one of the nearby parks, its welcoming smell of freshly baked bread makes me think of the “Sentinel of Liberty” and his fellow comic heroes.

The connection is simple, though like most memories, its resonances are complex. When I was 11 we moved briefly to the fishing port of Brixham in Devon, the same county as the farm I’d grown up in. It was and still is a small town. In those days it was a rough, trawler-town, street-brawling kind of place. The fishing boats still operate from the port, but the place has since grown more “sophisticated”.

But even then the modest new development near a secluded cove and beach to which we moved seemed almost like an artist’s rendering of gentle urban life to me. And the flimsy, newly built maisonette looked a little like a doll’s house after the rough brick farmhouse I’d grown up in.

The main attraction of the place was supposed to be the beach. But more important for me was that the house was a gentle stroll away from a bakery and a newsagent’s.

Coming from life on the farm, where it would have taken several hours to reach the nearest shops on foot, walking down a pavement (sidewalk) was something of a novelty.

That it was completely clear of cow manure feels, looking back, almost like a sign of decadence. No need to take our Wellington boots off at the door. No need to wear them at all!

On Saturdays we’d walk in flimsy shoes, like country mice visiting their town cousins, along the uncannily clean streets to buy the latest comic from the newsagent’s, marvelling at the ease of it all, and find ourselves overwhelmed by the smell of freshly baked bread from the bakery next door.

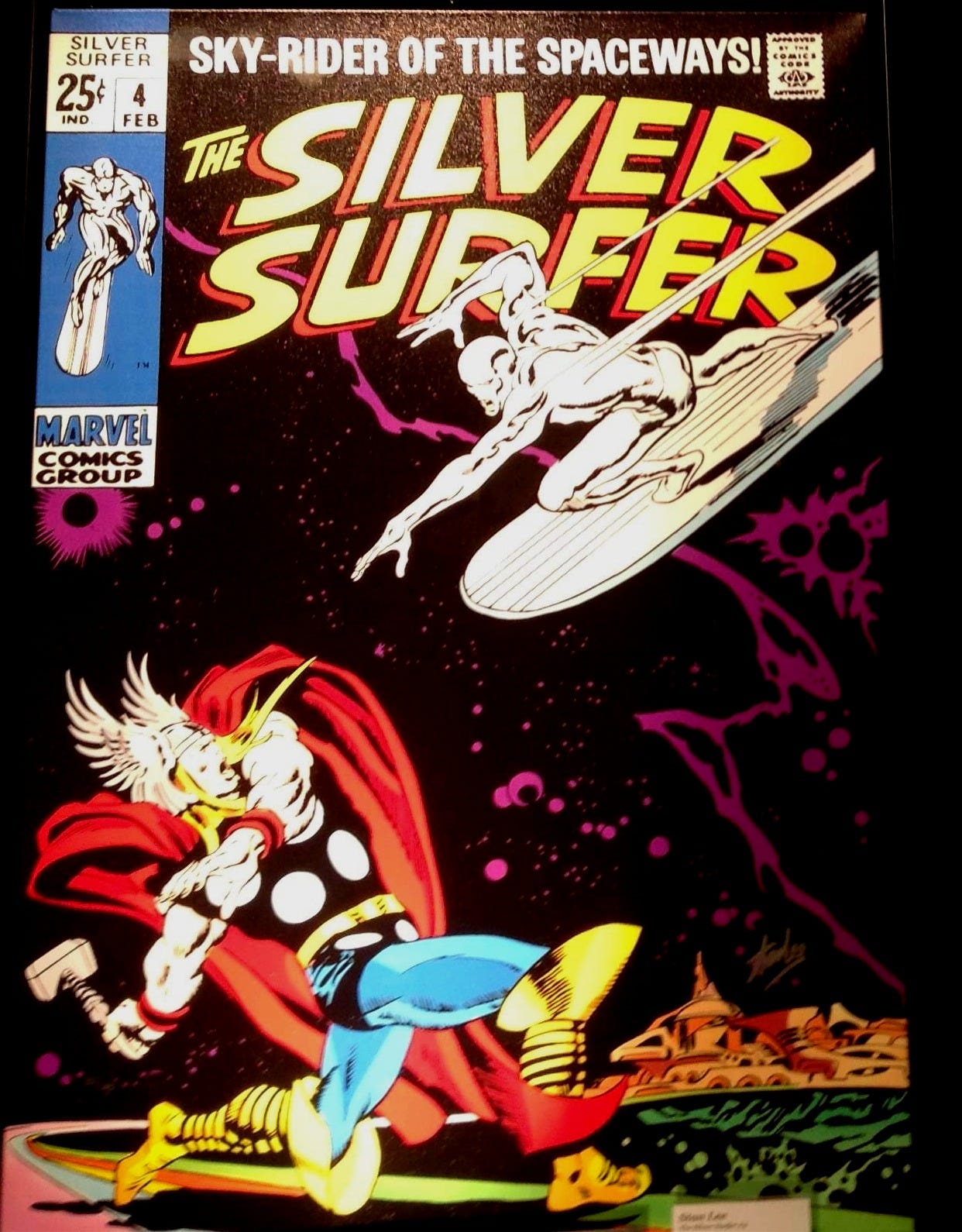

I don’t remember exactly what we’d buy in the bakery — probably, when permitted, a cream or jam doughnut. But I vividly recall the excitement of discovering the glossy pages of the comics featuring Captain America, the Hulk, or, best of all, the Silver Surfer.

The smell of the new magazines/comics was a secondary note to the dominant bouquet of the fresh bread next door, but it certainly added to the moment and to the complexity of the memory.

The Marvel characters were, of course, from a world that was impossibly far away – America. Their lurid universe of full-volume action and impending global destruction was almost indistinguishable in my mind from the streets of San Francisco, the deserts in cowboy films or the brooding megalopolises of Chicago or New York, which I knew from the humble TV we used to watch in the old farmhouse.

For what remained of that summer, I became fascinated by the vivid colours, stylish artwork and often pithy dialogue of those comics, eagerly purchased with a few pocket-warmed coins of the new pence that had recently taken over from shillings and pennies.

Decimalisation of the currency was a step towards modernity for Britain. For me, coming across the Marvel galaxy was more like discovering life on another planet.

It wasn’t just the astonishing artwork with its pirouetting superheroes or villains of vivid colours; the words, too, were different from what I’d read before. I remember a phrase from one of the comics where the writer knowingly misquoted a famous line as “music has charm to soothe the savage beast” to suit their purpose (I seem to recall that the music was calming some rampaging dinosaurs). This somehow impressed me at the time as incredibly clever. It was perhaps my first experience of someone playing around with words in what seemed like a “learned” way.

And the forlorn demeanour of my favourite character, the Silver Surfer – isolated, searching for a home – feels, in hindsight, to have been in tune with the changes in the family. My father had just sold the farm, and we’d not yet settled on the next place to live.1

*

To be honest, I don’t go in the Noguchiya bakery often, but when I do, it’s not really with the intention of enjoying the journey back to those childhood days spent reading The Avengers or cramming doughnuts oozing with raspberry jam into my mouth.

No, when I go there, it’s to buy my favourite Japanese pastry or bun, a “melon pan” メロンパン. 2

For a melon pan to be good, the outside needs to be crispy and slightly sugary, the inside soft and fluffy, almost diaphanous. They aren’t supposed to taste of melons; it’s their vague physical similarity to a cantaloupe that I believe justifies their name.

I’m still waiting to encounter the perfect melon pan,3 but I enjoy the ones baked at Noguchiya, where if I’m lucky I can enjoy them still warm from the oven, with a firm exterior and deliciously soft on the inside.

I had also been enjoying the specimens from Seven Eleven, which had a crispy surface scored by ravines of sugar. But they’ve just changed the recipe and made the outside softer. Not all change is for the better, as we know. The new version is a huge disappointment.

Unusually, the melon pan from my local supermarket is pale green and melon flavoured. This is an offence to purists, perhaps, but I enjoy them; they taste like the shade of a tree on a hot summer’s day.

*

That bakery in Brixham has long been closed, and it’s decades since I read a Marvel comic.

Gone, too, is my direct access to these memories of that brief childhood memory of town life. However, they remain preserved in the fragrant amber of the smell of freshly baked bread.

To be honest, the melon pan hasn’t exactly become my madeleine. The sight of one doesn’t flood me with nostalgia for times past.

Yet this sweet pastry, which I’ve known for half my adult life, has become a kind of comfort food for me. And it will sometimes lure me into the bakery, where I can once more cloak myself in the rich cape of the oven’s warm fragrance.

As the memories waft back to me, carried by the warm smells of the bakery’s ovens, it can feel, fleetingly, like I’m stepping back into a universe of comic-book adventure far from this world’s woes.

At first, the sharp pang of nostalgia this produces in me brings to mind the opening of Shakespeare’s Sonnet 30:

When to the sessions of sweet silent thought

I summon up remembrance of things past,

I sigh the lack of many a thing I sought,

And with old woes new wail my dear time's waste.

But as I clutch my tray and hand over a few silvery coins, the near epiphany that Sonnet 30 achieves in its concluding couplet begins to find its counterpart in the smell and taste of that still-warm melon pan:

But if the while I think on thee, dear friend,

All losses are restor'd, and sorrows end.

It’s a lot to expect a local bakery thousands of miles away from where I grew up to continue to restore all my losses or end my sorrows.

But for now it’s good to know that the simple smell of warm dough will do something no superhero can: transport me at the speed of “sweet silent thought” to connect me with my past.

Months later, we ended up many miles inland, in a house just within the catchment area of the secondary school we’d always expected to attend, a place with a surprising gravitational force. We moved into a house near a tiny village with a field attached. There would be no more pavements or bakeries for a while.

If I do, perhaps I should call it “Ultra-Pan” after Ultraman, one of Japan’s most famous live-action television series.

What a joy to find your essay in my inbox this morning. You are a master at weaving your personal story into a narrative that brings us into a world influenced by the cultural, social, historical, and literary traditions that allow readers to relate through our own lives. We all have some equivalent of melon bread. Mine is “Christmas bread,” fragrant with cardamom and raisins, iced with an almond-extract glaze, a Swedish recipe handed down from my grandmother to my mother to me. I make it for special occasions throughout the year.

I don’t have memories of comic books - they were banned in my household - but a walk with my brothers to a decades-old library, bringing home a stack of books, reading them and returning for more, was a highlight of my Saturdays. I must have been about four or five. We stopped at Jack’s store (a bit seedy, they sold chewing tobacco and low-ABV beer) for penny candy along the way.

About the “Music has charms” misquote: it was a deliberate way for the publishers to sneak in some Shakespeare, with more than one possible reason. It was puritanical - oh, how boys would have been titillated (sorry!) by the word “breast!”; - a sly way to create respectability through literary allusions; and a genuine, widespread, innocent misreading of Shakespeare. Americans did not study his work until high school, if we did at all. “Music hath charms to soothe the savage beast” was, in fact, how I learned the quote.

Thank you again, Jeffrey, for a delightful read. Proust’s madeleine, intentional or not.

Oh, this brings back memories...

When I was in West Africa, the staple grains, millet and rice, were, of course, boiled over open fires. But they did have some beehive clay oven bakeries scattered throughout the village, where long thin loaves of imported white flour were baked, but only enough for the day, as the bread became iron hard overnight. If you wanted bread that day, you had to buy it early - by late afternoon, there would be none left. The neighbourhood food sellers offered whole or half loaves spread with a spicy bean sauce, called nebbe, for lunch. It was delicious.

In Athens, the neighbourhood bakeries made a wide variety of loaves. My favorite was identified as artos, which is the ancient Biblical Greek word for bread. Some artos is specially stamped in licensed bakeries for use in the Orthodox Eucharist, but other loaves of artos, baked in large squares and sold in halves or quarters, are for regular consumption. It tastes like a sourdough bread and, if well wrapped to keep the outer crust from drying out, will last for up to a week (although it is so good it is usually finished long before).

On Baffin Island, the Inuit traditional bread is bannock, which is essentially a doughy quickbread that could be baked over an open fire in a pan or even twisted around a stick. Baking with flour is something the Inuit learned from whalers and fur traders, but they have become masters in the art - their homemade doughnuts were second to none.