Watching the gathered soldiers from across the land boarding ships (for their duty), there is nothing that can be done.1

My wife must be longing for me deeply. I even see her reflection in the water I drink—she cannot be forgotten in this world. 2

*

I have come to the borders of sleep. 3

Their feet had come to the end of the world. 4

Only the love of comrades sweetens all. 5

While researching my essay on the kimori, I came across the story of the 防人, the sakimori. At first, deceived by the superficial similarity of the “mori” in both expressions, I thought their story might be similar to that of the persimmon guardians. But not only are the terms etymologically distinct, the meanings are very different. There is a common sense of “guardian,” but there the similarities end.

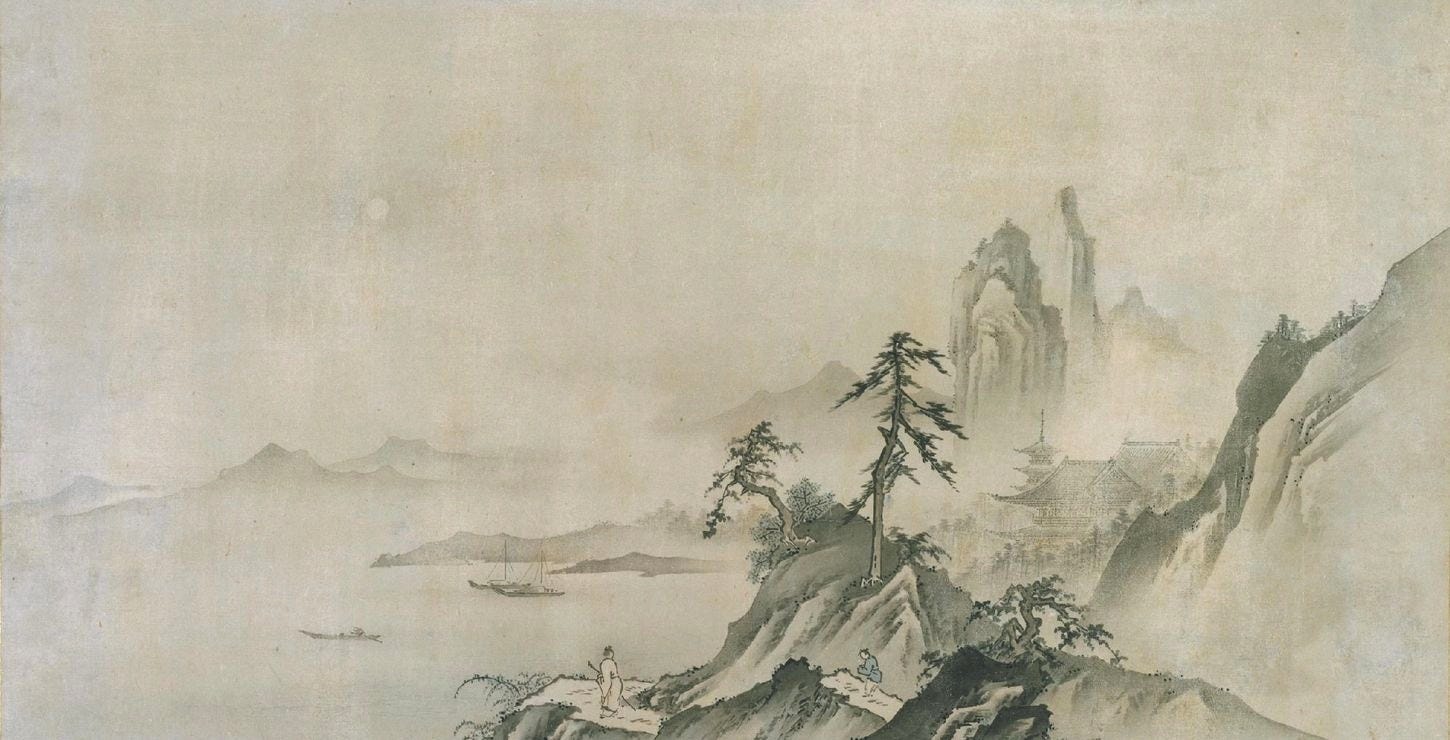

The sakimori were frontier guards in Japan in the 7th & 8th centuries. Some were also poets. Conscripted in the 7th century into the service of the emperor, these recruits were taken mostly from the eastern provinces of Japan to the southern island of Kyushu. Their mission was to guard against a possible invasion from the Chinese, in the lead-up to and aftermath of the Yamamoto regime’s disastrous meddling in the fate of Korea, which was then the subject of Chinese imperial ambitions. Routed along with their Korean allies in the Battle of Hakusukinoe (as it’s known in Japan) in 663, the regime expected punitive action from the Tang dynasty, who were allied with the Silla kingdom in Korea.

The onslaught never came. But the frontier soldiers, who had to pay for their own food and arms, underwent severe hardships, a huge distance from home. Even now, in Ibaraki, once known as Hitachi, one of the Eastern Provinces from which the frontier guards were recruited, there’s an annual festival to celebrate the sakimori who sacrificed so much for their country.

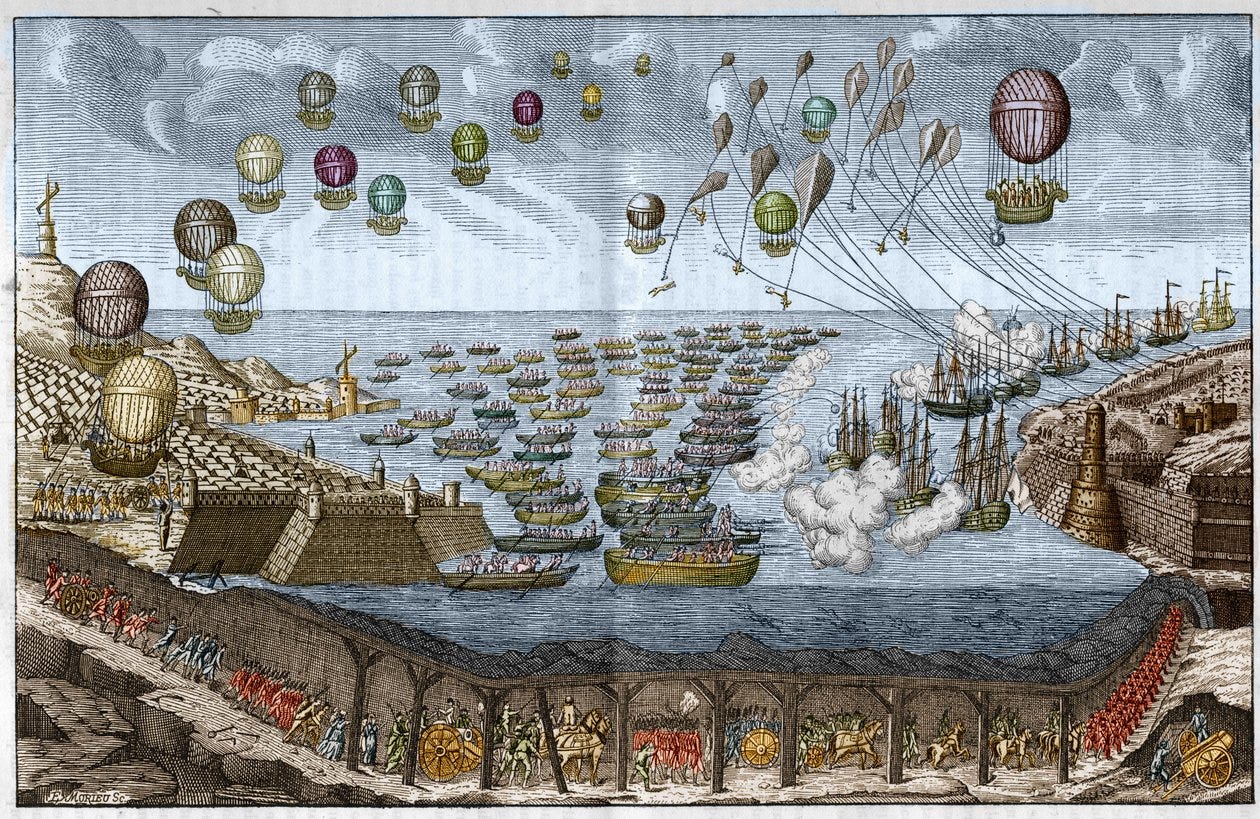

The threat of an invasion that was never realised makes me think of the fortifications, such as the Martello Towers, around the south coast of England (and elsewhere), erected against the threat of invasion during the Napoleonic Wars.

When I think of those defences along the English Channel coast, I tend to hear the voices of Thomas Hardy’s sardonic, sceptical poem Channel Firing from 1914, which ends with the sounds of war disturbing the most ancient sites of the nearby country:

Again the guns disturbed the hour,

Roaring their readiness to avenge,

As far inland as Stourton Tower,

And Camelot, and starlit Stonehenge.

It’s a reminder that wars don’t just affect those who fight in them.

*

The first poem of the Sakimori that I quoted above hinted at the sense of helplessness that the soldiers might have felt—they did not own their fate. And the second suggests the bitterness of separation from family that many will have felt.

Such feelings were far from unique in the period—you get a strong sense of it in some writing from the Tang dynasty in China. This includes the prose of Han Yu (768–824), for example, in his desperately sad essay “Lament for my Nephew.”6 And in a poem also directed to his nephew, he wrote:

One dawn I petitioned to the court above,

By dusk I was exiled, far from love. 7

I, too, have known what it is to be distant from loved ones for extended periods and have even fancied myself, preposterously, in exile. But I can only enter the experience of these frontier poets, these soldier-writers in exile, through the words they left behind.

We know of the poems of the sakimori because some of their poems were collected in the most celebrated of anthologies of classical Japanese poems, the Man'yōshū, compiled some time after 759. This anthology, once seen as a symbol of patriotism, is now celebrated for its democratic inclusion of poems by commoners along with those by the Emperor and other nobles. You can access the text here.

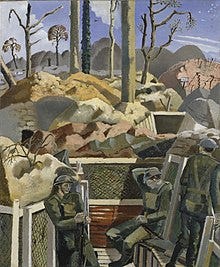

Reading about the sakimori, uprooted from their homeland to support battles and imperial ambitions they may not have understood, even as they expressed loyalty to their country, I was reminded of the sad songs of the war poets from the First World War. I included snippets from them above just after the two quotes from the sakimori.

Though separated by more than a millennium and thousands of miles, and belonging to a very different culture, there are the common themes of separation and loneliness, as well as human solidarity in the face of the whims of fate and the fortunes of war.

Although the sakimori seem to have been outwardly loyal to the emperor and to their cause, we know that some First World War poets were sceptical of the imperial purposes of the war. Was it for this the clay grew tall? Wilfred Owen asked in one of his poems. And poet and musician Ivor Gurney, having expressed his love of country at the start of his poem Servitude, was scathing about those in authority, about being

scanned curiously o'er

By fools made brazen by conceit.

*

I feel grateful to have come across the moving words of the sakimori so many centuries after they were written. To me, they almost seem as close—or distant—as the celebrated war poetry of Wilfred Owen and other 20th-century English-language war poets. And just as moving.

Let’s end, then, with a few of the songs of the sentinels, those poems composed by these frontier poets in their sometimes rushed and always open-ended missions to protect the coasts of Japan.

764 8

Tread imperial command

I have received: from tomorrow

I will sleep with the grass,

No wife being by me.

—By Mononobé Akimoch

766

Even in a strange land I see

The flowers of each season bloom—

The flowers I have known at home.

Why is it that there grows

No flower called ‘Mother’?

—By Hasetsukabé Mamaro

771

How I regret it now—

In the flurry of departure,

As of the waterfowl taking to fight,

I came away without speaking a word

To my father and my mother.

—By Udobé Ushimaro, a guard

From Lights Out by Edward Thomas. Ivor Gurney set the poem to music, and you can hear a lovely version here.

From Spring Offensive by Wilfred Owen.

Yu, Han. Collected Works of Han Yu: Poetry and Prose (p. 130). Neotao Studio. Kindle Edition.

Yu, Han. Collected Works of Han Yu: Poetry and Prose (p. 86). Neotao Studio. Kindle Edition.

The numbers here refer to their entry number in the Man'yōshū.

Jeffrey, This gorgeous essay about these frontier poets (thinking of Ukraine, of course, as Trump drops US help and leaves these soldier "at sea")—I'm also reminded of what these poets captured and that took me to Kundera's _Art of the Novel_ where he says in the work of the great storytellers like Boccaccio and Dante, "we can make out this conviction: It is through action that man steps forth from the repetitive universe of the everyday where each person resembles every other person; it is through action that he distinguishes himself from others and becomes an individual."

Lovely poems, Jeffrey, and lovely essay, of course.

Sadly, time goes by, but mankind doesn't seem to learn from its bellicose past.