Sub Rosa

Love, death, and the eternal mystery of flowers

As a young man, I didn’t pay much attention to flowers.

Of course, they were always there: the primroses studding the hedge on the lane at the farm I grew up on, the lupins and snapdragons, and even sunflowers that my mother somehow had time to grow in the back garden. There were also the foxgloves waving at me from the hedgerows as I traipsed across the farm in summer.

Later came the poets to draw flowers to my attention: Wordsworth with his daffodils and Chaucer with his celebration of the beauty of Venus and her

rose gerland, fressh and wel smellynge. 1

And then in marched Robert Browning, thinking of England while travelling abroad and imagining how

my blossom'd pear-tree in the hedge

Leans to the field and scatters on the clover

Blossoms and dewdrops 2

Much, much later, as I grieved the loss of my father, I would marvel at Louise Glück’s more subtle evocation of flowers when, for solace, I folded myself like a crushed blossom into the pages of her Collected Poems.

Now flowers are the essential punctuation marks of my morning walks, gently parsing the syntax of sight and thought and memory into something like sense.

But I still think of flowers as a secret society, which, in quiet conclave, whispers a foreign tongue. I don’t feel excluded; I’m just in awe of their quiet and beautiful otherness. There’s no threat in their hushed conferences in the summer breeze or autumn wind, just a vast mystery to admire.

*

Of course, flowers have propagated giant thickets of folklore. Their “meaning” in human eyes can vary from culture to culture and from person to person.

For example, having once proudly presented someone with what they later termed “funeral flowers,” I’m now wary of giving flowers as presents.

Flowers are beautifully alien to me. A catalogue of them may contain more Latin than the long-forgotten textbook I studied at school. And while scientists taxonomise, artists celebrate in paint, and gardeners glean ancient wisdom from peers to help their blooms thrive, I do none of these things. Not being one of the adepts, I can only cast shy glances in their direction, never expecting a response.

The flowers I admire are always in other people’s gardens or growing wild in fields or hedgerows.

*

Recently, I’ve been thinking of the most carefully curated of flowers: roses, those prickly defenders against the careless reaching hand.

For the roses

In these famous lines from his poem Burnt Norton, the first section of the Four Quartets, Eliot captured a truth about the set piece of our admiration for these flowers.

Yet the formality of our regard for them does not detract from their beauty. I’ve admired them in local gardens, including at my parents’ house, quite as much as I’ve enjoyed them in their stately setting at Hampton Court, Regent’s Park, or Shinjuku Gyoen in Tokyo.

*

Roses are more heavily laden with cultural meanings than a gardener’s wheelbarrow. If their sharp spines can make us bleed, their subtle messages can confound us into floral solecisms - should I give red, or pink, or white, or even purple?

Even how we write the word can seem to carry a message.

For example, the simplicity of the word in English or Spanish feels like it is matched in Japanese by the simple-sounding “bara.” This is most commonly written バラ using katakana, and children can soon learn to write it. But when spelt using kanji (Chinese characters), it is rendered 薔薇.

With a total of 51 brush or pen strokes, it's notoriously difficult to write, and most people will avoid doing so. To me, it seems those two characters form an impenetrable grove, like the thorn hedge that grows around the castle in the story of Sleeping Beauty. It’s as if the complex and guarded beauty of the rose had found its counterpart in script.

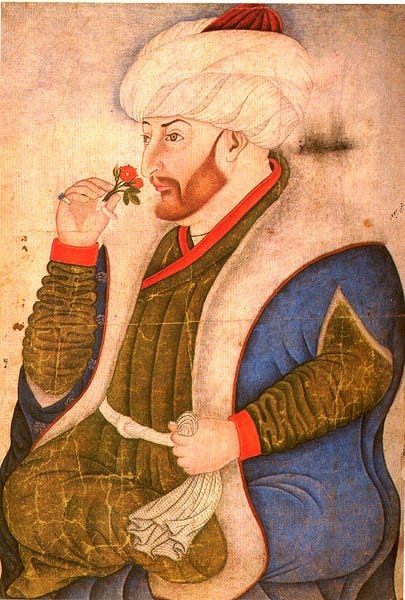

I sometimes remember the roses in Turkey. When I lived there, the President’s surname was “Gül” - the Turkish word for rose. Years later, when I was clearing out my mother’s things in the barren months after her death, I found many rose-scented perfumes. They reminded me of the time I passed through the town of Isparta, where 65% of the world’s rose oil is produced.

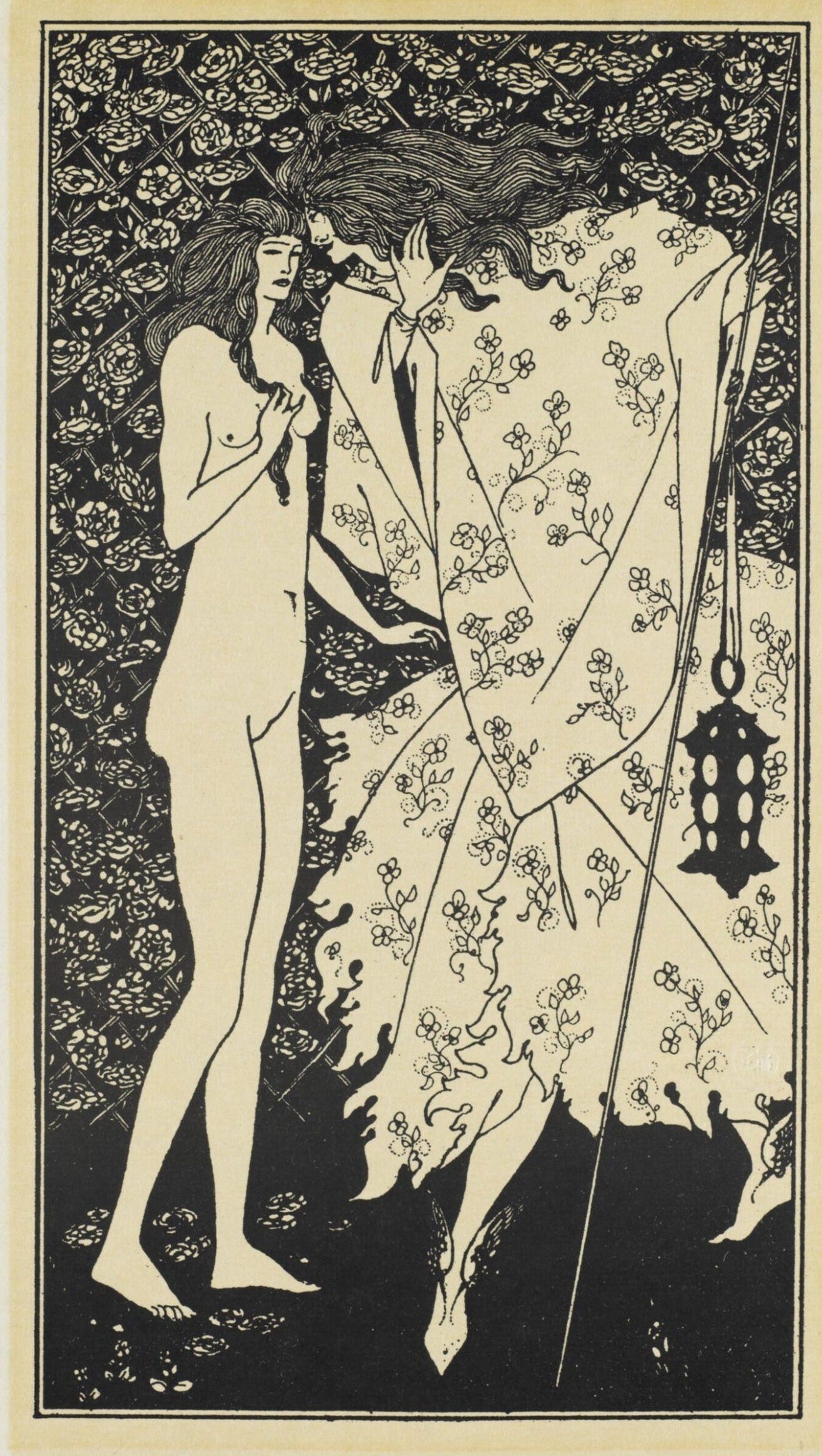

And recently, as I wandered through the Beardsley exhibition in Tokyo I stumbled with bewildered delight into his mysterious rose garden:

*

But when I think of roses, I mostly think of my mother. She loved the yellow and red blooms that were the highlight of the modest garden she tended for the last forty years of her life.

She would send me photos of them during my foreign postings, and when I visited, I would always spend time admiring them with her.

And she cherished the arch made by my father that formed a rose bower for her, where the flowers joined in triumphant celebration of their enduring love for each other.

Married for over 67 years until my father’s death separated them, both my parents are gone now.

If they had been buried according to the old custom in England, I might have been able to write with Thomas Hardy about how:

Soon will be growing

Green blades from her mound,

And daisies be showing

Like stars on the ground,

Till she form part of them 3

But they were not buried in the earth.

In Louise Glück’s poem Lover of Flowers (1990), 4 the poet depicts her sister choosing flowers for her mother’s garden:

It’s her garden, every flower

Planted for my father. They both see

The house as his true grave.

I now realise that’s how I’ve thought of my parents’ house, which I tended for over half a year following my mother’s death.

That house became my parents’ true grave, garlanded by the roses she planted.

But now the house is sold, my mother’s garden is tended by other hands, and I don’t know what’s become of the roses.

My parents, who were cremated according to modern and secular rites, have disappeared into the thinning air. Their remains do not nourish “significant soil.” 5

Yet as I think back to those two sad, separate days when the smoke rose and my parents’ atoms mingled forever with the atmosphere, as I remember their “true grave” in the lost rose garden, I wonder, in some wisp of my imagination, whether the final entwining lines of Little Gidding might have been true at the moment we witnessed their last journeys towards a final transformation:

When the tongues of flame are in-folded

Into the crowned knot of fire

And the fire and the rose are one. 6

From The Knight’s Tale. The rose was, of course, a symbol of love, associated with Venus.

From the collection Ararat, p. 207 of the Collected Poems.

The phrase is from Eliot’s Dry Salvages.

The last lines of Eliot’s Little Gidding, the last of the Four Quartets.

Such a touching way of remembering your parents. My mother loved roses, too.

My parents were cremated, but we put their ashes in a memorial in the churchyard of the church they worshipped at, so there is still somewhere to visit and leave flowers.

Mainly they live in my memories, though.

Jeffrey,

You write so beautifully. Your essay is filled with tender reminiscence, thoughtful quotes, and meaningful information.

I have always loved flowers, especially peonies and sunflowers; where I live now in Ohio, I was not sure the sandy soil would accommodate them. I have been delightfully surprised. My mother loved roses and could spend hours in her gardens, tending the flowers. She also kept a vegetable garden. How she did both, which amounted to a second job, I'm not sure.