I’ll say it straight away: Surrealism has never been among my favourite modes of art, whether in painting or literature. Of course, I went through the usual teenage infatuation with Dali as a teenager, and I retain admiration for individual artists like Magritte, but as a movement, I feel only a limited connection to it. One reason may be its association with dreams. I’m not sure if Oscar Wilde actually said that the most frightening words in the English language are “I had a very interesting dream last night.” But I agree with the sentiment.

So it was little more than curiosity that tempted me into my local museum earlier this year to see an exhibition about “Surrealism and Japan" (plus the fact that it was free). And while I didn’t go away with a burning desire to immerse fully myself in the art of that tradition, I did leave armed with some stimulating new perspectives on how Surrealism was taken up by artists in Japan.

*

The spark for the exhibition came from the 100th anniversary of the Manifeste du Surréalisme published in 1924 by André Breton. The chronological layout of the art charted the shifting influence of the movement among artists in Japan from the 1920s onwards.

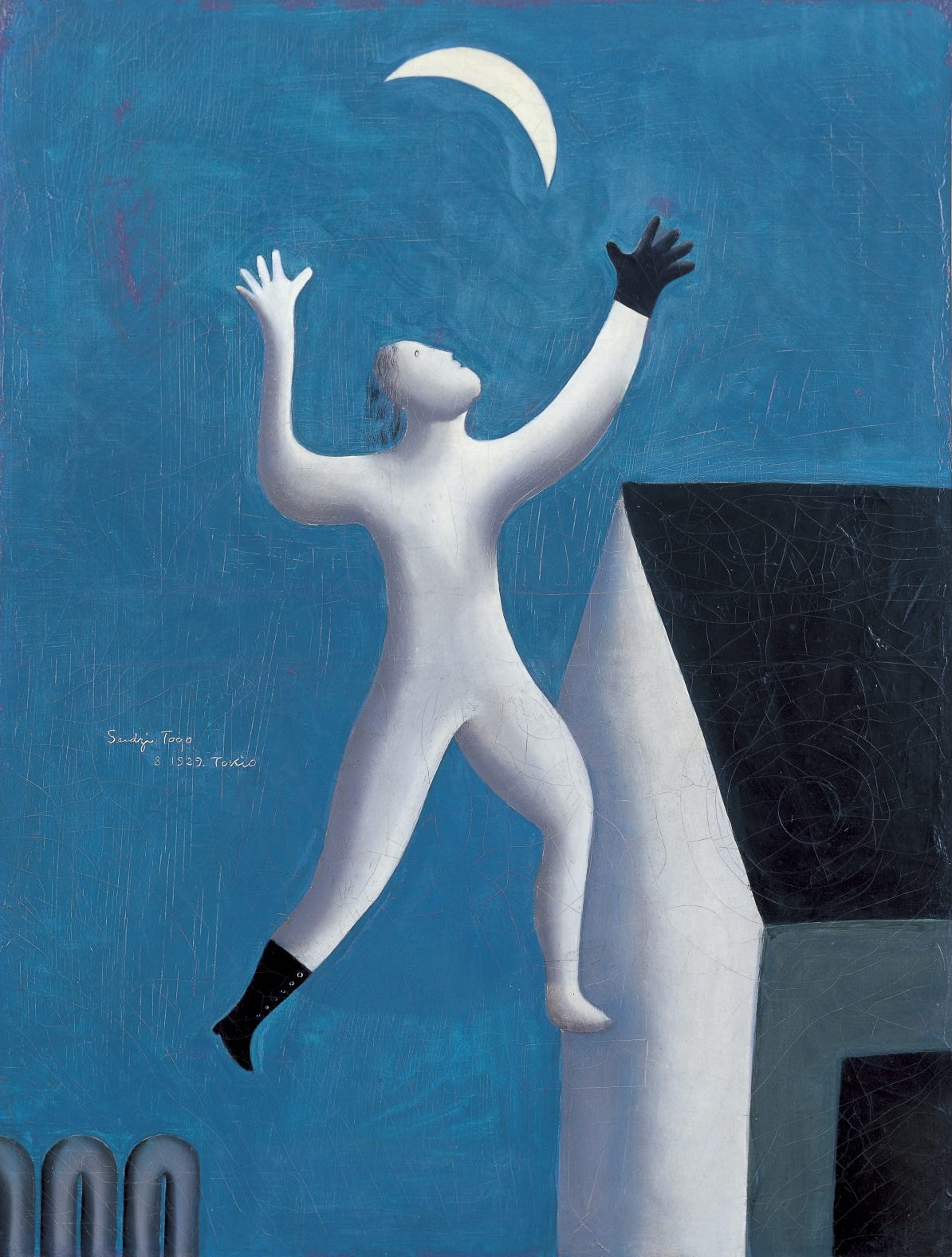

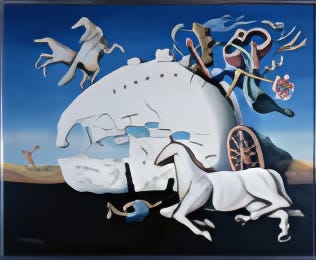

The works from the first decade or so included some attractive paintings, such as Seiji Togo’s Surrealistic Stroll, Hironobu Yazaki’s Illusion of the Plateau, and Yonekura Hisahito’s The Crisis of Europe. But the way the last of these titles foregrounds Europe summed up to me what I was beginning to feel—that at this point, Surrealism was only roughly grafted onto the Japanese artists’ sensibilities. In short, to me, the art felt a little derivative. But decide for yourself:

*

The exhibition began to grab my attention, however, when I saw works from the late 1930s and the 1940s. During the rise of militaristic authoritarianism in Japan at that time, dissent was suppressed, and Surrealism was mistrusted as subervative. At the same time, and this may be no coincidence, the art produced under this label started to become (again, for me) more interesting. A particularly good example is the startling work of Hironobu Yazaki (1914–1944): The Intention to Kill on the Street and A Woman Dressing Red Clothes and a Monster, both capture a sense of pervasive violence of a society under such a regime.

*

The horror of war itself was the subject of work by Chimei Hamada, who created a series of unnerving works with titles such as Elegy for a New Conscript: Sentinel and Elegy for a New Conscript: Landscape (A Corner), both below. These are bleak yet moving works that harness the psychic energy of the movement in dealing with harrowing subject matter. They are, in the words of the critic Ian Buruma, "a kind of surrealist protest art.”

*

On the evidence of this exhibition, the movement maintained some of this energy as prosperity began to return to Japan in the 1950s. The material comforts of the post-war settlement were real enough, but they came at the cost, as some saw it, of a new susbervience, this time to a Western geopolitical view that defined the world as a contest between the West and communism. This contest, of course, was played out bloodily in many proxy wars around the world, including in Asia. Japan’s role, as later made explicit by its Prime Minister Nakasone, was to be an “unsinkable aircraft carrier.”1

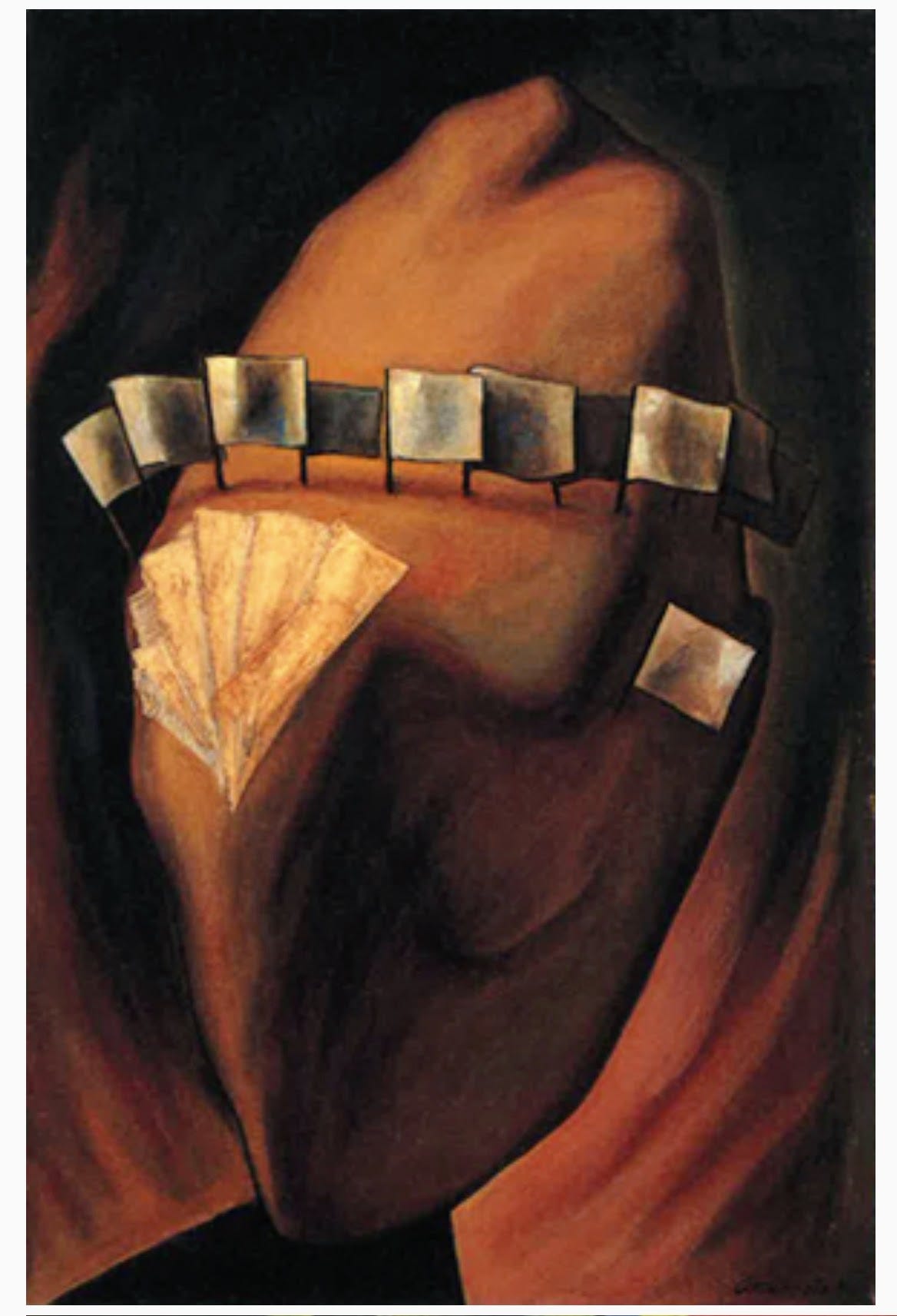

The most notable works of this period in the exhibition I saw were by Kikuji Yamashita. His The Tale of New Japan seems to suggest the predatory nature of an imported capitalist culture.

Another impressive work from the later period is the ominously titled Gloom by Taro Okamoto, a major post-war artist who made extensive use of surrealist techniques in his work. Okamoto often worked on a large scale; an example of this is the mural at Shibuya Station, not far from the Shibuya Scramble made famous by Sofia Coppola’s 2003 film Lost in Translation. Originally commissioned by a luxury hotel in Mexico, Okamoto’s work was lost for decades. Titled Myth of Tomorrow, it depicts Okamoto's reflections on the horrific suffering brought about by the nuclear arms race of the Cold War and fear of nuclear weapons.

*

Commenting on this period, Buruma has said: “Many Japanese artists and intellectuals in the 1950s rebelled against the overwhelming American influence of the immediate postwar by looking to Europe, especially France, for ideas.”

Yet my impression based on what I saw in this ultimately stimulating exhibition was that post-war Japanese Surrealism gained its power less through following European models than through introspective psychological exploration of national trauma and politics.

I’m not sure I learnt much about Surrealism from the exhibition, but the best of the work on display here certainly gave me new avenues to explore regarding post-war Japanese history and art.

Yasuhiro Nakasone was Japan’s Prime Minister from 1982 to 1987. He had actually started out his political career fiercely opposing the US post-war occupation of the country. This same phrase was once used to describe the UK.

Love this. I'm a huge fan of surrealism in literature and film. Less so for paintings but I still find the work and concepts so expansive. I do understand why people feel less enthused by it though than I. Thanks for sharing all of these artists and their work. I had never heard of many of them and love the historical context for why the Japanese turned towards France for a way to reduce or reject the influence of America in post-WWII Japan. Thank you!

Hmm. Surrealism is always a stretch for me, but you have made these intellectually and historically interesting.