On the way to a lake near the Arakawa River outside Tokyo recently, I found myself walking through a mixed neighbourhood—one of those with residential buildings, small factories, and plots of waste ground all mixed together. I love these indeterminate spaces, not quite one thing or another. You never know what you are going to see.

Or hear.

Because just as I passed a rather nondescript prefab partially hidden behind a clump of trees, I heard a sound that stirred a memory. The Pompey Chimes.

*

The Pompey Chimes is the name given to the oldest supporters’ chant in English football (soccer).1

Pompey, I should add, is pronounced Pom-pee (stress on the first syllable) and not like the ancient Roman city, Pompeii (“Pom-Pay”), which on August 24, 79 CE, was destroyed by a huge eruption from Mount Vesuvius.

Pompey is the nickname for Portsmouth, the naval city on the south coast of England and the birthplace of both my parents. The city does have Roman origins, however, and has also a special place in British military history.

In the early-19th century, Portsmouth was regarded as the most heavily fortified city in the world and was called "the world's greatest naval port" at the height of the British Empire throughout the so-called “Pax Britannica.” Due to its prominence as a naval port, the city suffered extensively from German bombing during the Second World War; both my parents were evacuated to a safer place for at least some of the war.

The city survived, but after 1945, it began a slower kind of decline. The war had been won, but the empire that the city had helped to sustain was lost.

*

My father, born in the early 1930s, was an avid Pompey fan all his life. The team were the champions of English football in 1949 and 1950, while my father was still in his teens. This must have buoyed his youthful enthusiasm, but he never wavered in his support even when the club lost its grip on the championship before descending into the lower leagues.

I was never much of a football fan, but I vividly recall the sound of the Pompey Chimes sounding around the large stadium on the only occasion I went with my father to watch a match at their home ground, Fratton Park, when I was eleven or twelve.

To hear this sound now, as I walked through the outskirts of Tokyo, taking me back over fifty years to that rare day out with my father, seemed extraordinary.

*

It turned out that the nondescript building was a school. And it was in the 1950s that the same combination of notes used in the Pompey Chimes started being used by Japanese schools. Apparently, the previous way of marking the beginning and end of lessons sounded like an air raid siren, unsettling for a population still traumatised by years of war.

Cities devastated by wartime bombardments on civilian populations; that seemed like a connection.

But did that explain the use of these same notes in these distant places for such different purposes?

*

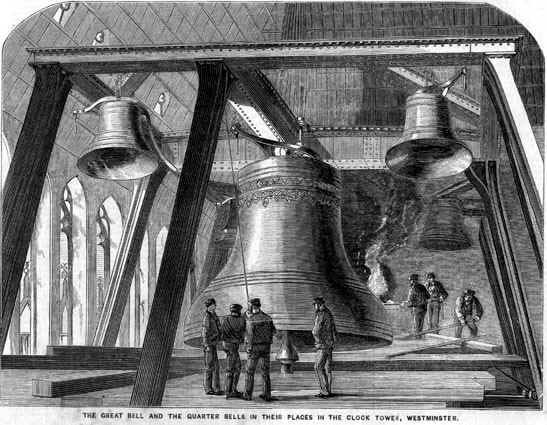

Punching more questions into my phone, I soon realised that both sets of chimes had a common source. The Westminster Quarters.

The tune was originally composed in 1793 for a new clock in the University Church in Cambridge. In 1851, the chimes were adopted for the new clock at the Palace of Westminster, where Big Ben hangs and where the melody is rung by a set of four quarter bells to mark each quarter-hour.

From there, the use of the Westminster Quarters spread. And it was possibly via their use in BBC broadcasts in East Asia during the 1940s and 1950s that the idea came to use them in Japanese schools.

As for the football chant, the Westminster Quarters had been used by the clock tower at Portsmouth Town Hall from 1890 and were sung as a way of encouraging their team by the supporters of the Royal Artillery (Portsmouth) Football Club. Soon after the founding of the professional club of Portsmouth FC in 1898, their supporters began to use the chant.

This simple tune, developing a rich cultural life of its own, accreting new meanings, and becoming part of new traditions around the world—it’s possible to see this as a rich pattern of the spread of cultural artefacts in a hyperconnected world, I thought.

But as I considered the Palace of Westminster and its famous tower and bell as ineluctable symbols of the British Empire at its height, I began to see this as also a ripple of influence from a former epicentre of imperialism. In my decades of living in other countries, I’ve stumbled over the vestiges of the British Empire many times. Indeed, it was hard not to, especially in Egypt and Hong Kong.

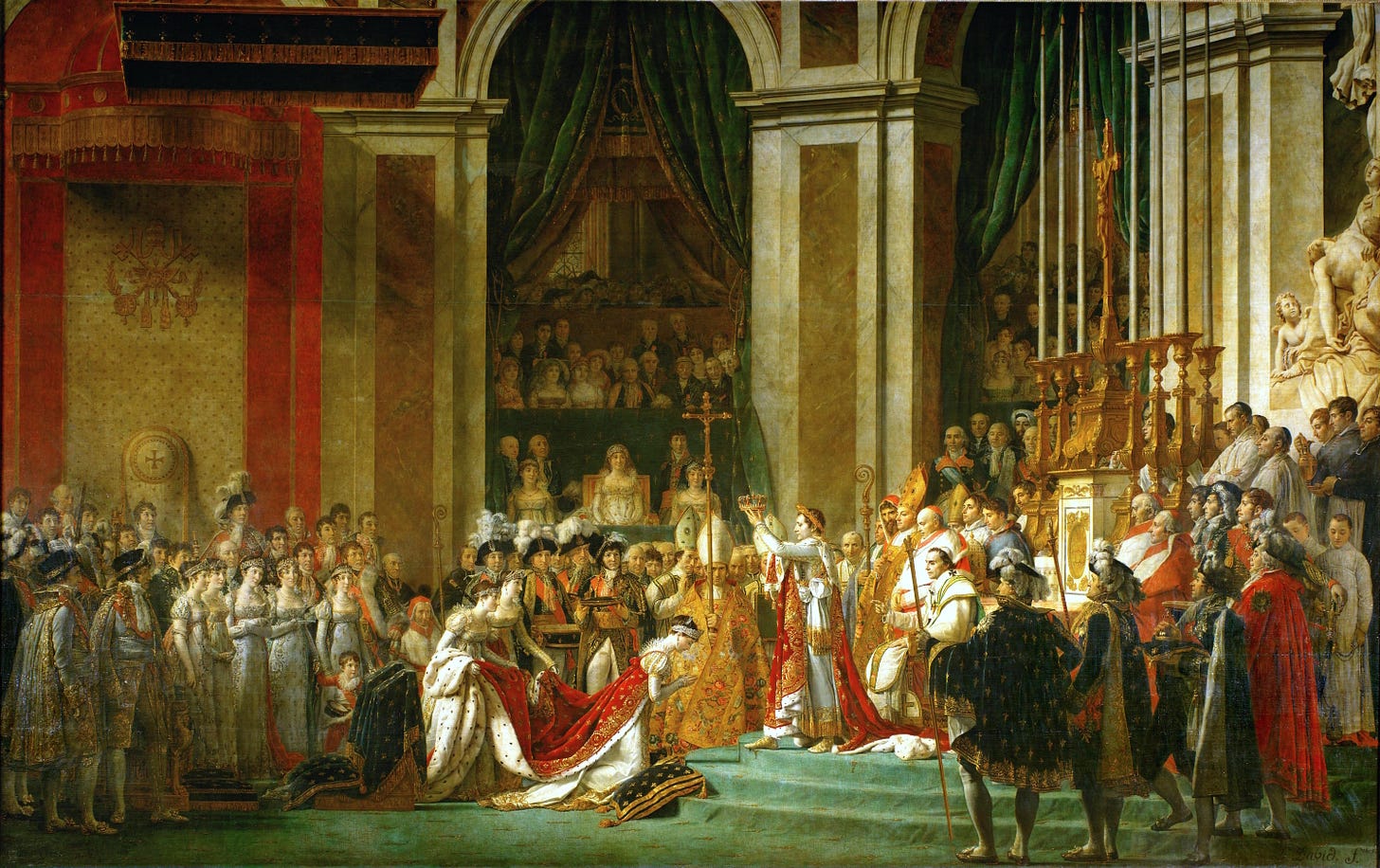

But in my school days, it struck me—I hadn’t studied the Empire at all. Our history textbooks taught us instead about the Second World War, the Napoleonic Wars, and the English Reformation, topics more readily given a positive national narrative, perhaps, than an empire that had been “lost.”

According to the former head of the British Museum, Neil MacGregor, comparing the uses of history in Britain and Germany, “What is very remarkable about German history as a whole is that the Germans use their history to think about the future, where the British tend to use their history to comfort themselves.”

The writer HG Wells said during the First World War, “Nineteen people out of twenty, the lower class and the middle class, knew no more of the empire than they did of the Argentine Republic or the Italian Renaissance.”

A character in Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses says, “The trouble with the Engenglish is that their hiss hiss history happened overseas, so they dodo don’t know what it means.” 2

These reflections reminded me that in a lifetime spent mostly living in other countries around the world, almost everybody I’ve met seemed more aware of the impact of the British Empire than my compatriots back home.

*

Continuing my walk, I could make out some of the tall buildings of Tokyo at the point where the river flows into the vast city. Arakawa (荒川) means “wild river." Back in 1910, the river’s banks collapsed, leading to 369 deaths and impacting around 1.5 million people.

Now I walked on in view of the 20th century flood protection gates and super levees and in the shadow of siren towers built to alert the local population in case of flooding.

Out on the lake, a dark flock of cormorants and a group of large white egrets skirmished in a bloodless—and apparently pointless—battle for supremacy of the waters. I wondered what Roman augurs would have made of that.

Behind me, the chimes echoed once more, though more distantly. I felt again the muted thrill of recognition of the familiar in an unfamiliar place. But the notes were no longer just a school bell or a reminder of a football chant; they floated to me as a whisper of the chronicles of our past, sounds not always captured in the histories that we choose to record.

The words are:

Play up Pompey,

Pompey play up!

Play up Pompey,

Pompey play up!

All three of these quotes are taken from the excellent Empireland: How Imperialism Has Shaped Modern Britain by Sathnam Sanghera. Viking, 2021.

Thanks, Ronald, I'll check out your post! I saw the painting a few years ago in an exhibition about painting and light (by the Tate, I think) and it astounded me. I jumped at the flimsy excuse to use it for my post. 🙂

Fascinating read Jeffrey. I love the painting you chose to tie in to the Napoleonic Wars. My mom was a David. Family lore passed on throughout the David for at least 4 or 5 generations is that we were related to Jacques Louis. I and quite a few 1st, 2nd and 3rd cousins have all tried to find that connection and have not been able to. My mom and I went to the Louvre to see his work in 72. I am not one to give up hope, so I am still looking for the link.