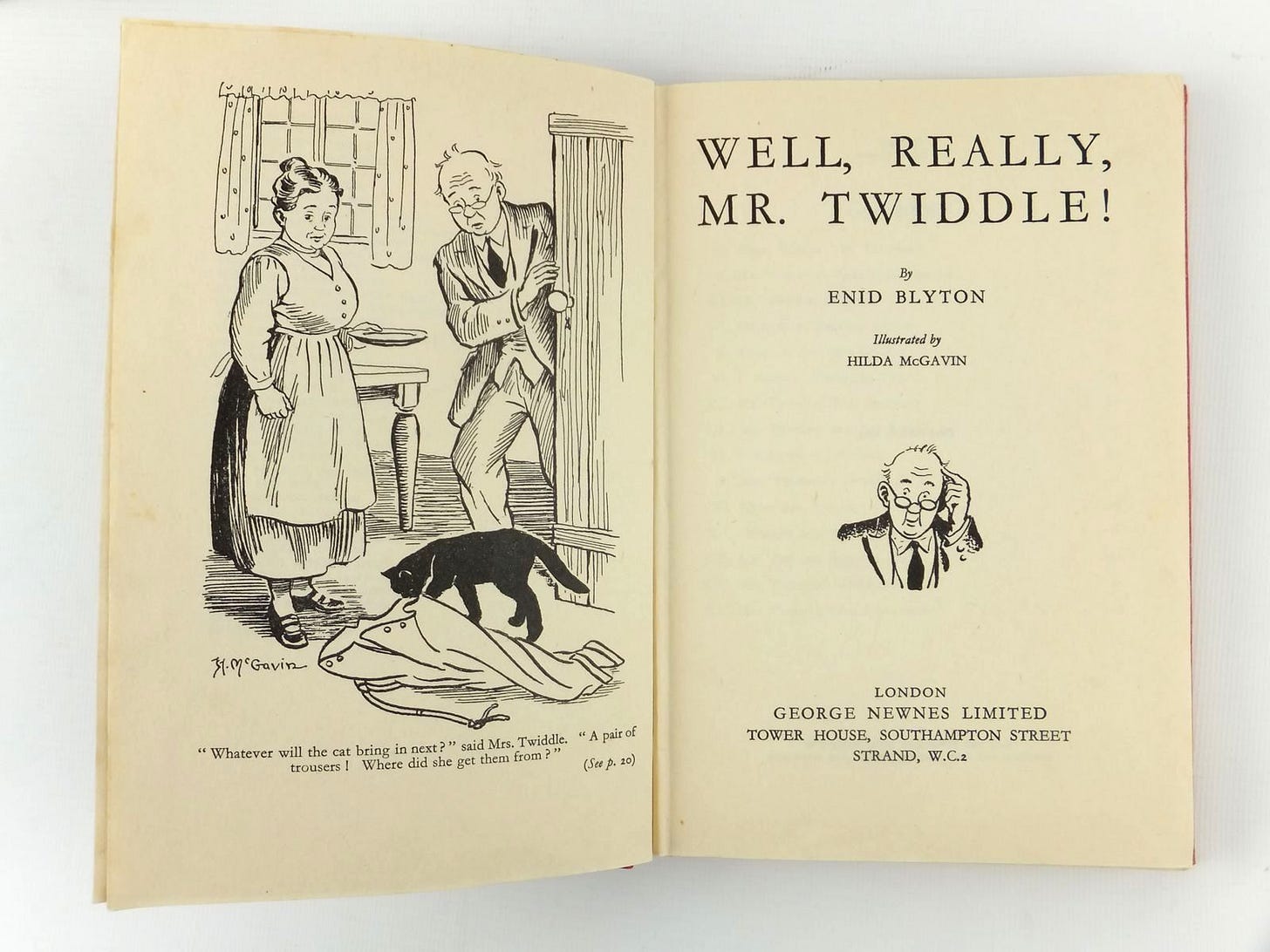

Well, Really, Mr. Twiddle!

The books we reach for (and perhaps should put back) when we’re sick

Something one of my university tutors said to me once about his reading habits always stuck in my mind.

“When I’m busy marking exams in the summer, I can’t face reading anything very demanding,” he told me one spring day at the end of our tutorial. “So every year I re-read Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows during that period.”

It was hardly a sensational fact to share, but coming from this serious-minded and decidedly unfrivolous older man, it had the weight of a meaningful disclosure. It was hard to think of him, indeed, enjoying the exploits of Mole, Badger, and Toad as I had done as a child. The admission made me warm to him.

So I felt I had precedent on my side when, many years later, while living in Mexico City in the 1990s, I found myself feverish due to a throat infection and unable to deal with whatever reading I was then embarked upon. I reached for a children’s book to keep my mind amused.

Beginning to suffer from occasional feverish hallucinations and feeling very sorry for myself, I felt unable to face a gripping story in the style of Jack London or RL Stevenson. (I had just proudly announced to colleagues at work that I hadn’t missed a day of work through sickness for ten years, and now this.)

Without knowing what I was looking for, I rummaged through the second-hand books my mother had recently sent over for her newest grandchildren, my sons. And then I found it—a book by Enid Blyton, a writer my mother had enjoyed as a child herself. Unfortunately, it wasn’t The Faraway Tree, a book that I knew had enchanted my mother as a solitary girl, living away from her family for years during her wartime evacuation in southern England. Indeed, the very title might have summed up how she felt, year after year, hardly seeing her parents, who lived in a city barely 40 miles away. But I’m sure my mother, ever with an eye for the bargain, came across this other book by Blyton in the charity shop where she worked and thought it would suit small boys just fine. The title was Well, Really, Mr Twiddle!

I pounced on the book and retired to my sick bed.

I was too sick to read anything at all for the first day, as I lay sweating and half-imagining that I was about to be abducted by aliens (my febrile dreams would win no prizes for best original story). But even the presence of the book had an effect. It helped me float back in time to my childhood, when I would have read about Mr Twiddle for the first time, and I found myself soothed by the idea of being five years old again.

And as I began to feel better, I was able to read a few pages at a time. The adventures of the Twiddles felt timeless as well as very much of their time. Mrs Twiddle looks after the house with the aid of a cleaning lady. Mr Twiddle doesn't seem to have a job. Perhaps they were a couple of independent wealth. The focus of the stories is on Mr Twiddle’s absent-mindedness. Each episode is very short and involves Mr Twiddle doing something daft, like fetching a goat and sheep from the field rather than bringing a coat and sheets in from the washing line. The storylines are childishly comic book-like in nature and very easy to follow. It felt perfect for what I needed, and I spent the next day or two dipping in and out of dreams and Mr Twiddle’s adventures without really ever knowing—or perhaps caring—which was which. I knew they were foolish, but they served a purpose.

Soon, though, came the moment of recovery; the fever abated and the patient began to sleep soundly. It was time to put away childish things. Mr and Mrs Twiddle were banished to the children’s room once again, where I believe they languished unread for the rest of our stay in Mexico.

Well, the reason for telling you all this was because last week I came down with a bad dose of flu and was confined to my bed for a few days. Once again, I was unable to focus my mind on anything as it drifted in some kind of viral haze. Maybe not brain fog, but certainly low clouds and light drizzle. Once again, I cast around for suitable reading material. To my surprise, I found I’d downloaded a copy of Well, Really, Mr Twiddle! onto my Kindle. So in this way, it had stayed with me during my long journey to Tokyo via the UK, other parts of Asia, Africa, and Europe. I don’t remember why I’d downloaded it. But here it was, in virtual form, still offering me a little portal into my childhood. Once again, I took what was on offer.

But this time, though, it felt different. Although I was too dizzy to focus on anything weightier and was able to pass the time with these familiar stories during the worst of my fever, I experienced no charming childhood flashbacks. I couldn’t enjoy these repetitive little tales and their rather absurd characters. I had to admit that the connection with the past had been broken. The portal to the past had disappeared.

I started to wonder why. Was I not ill enough? Or was it because of my own changed life circumstances?

Or was there something about Blyton and the way her reputation had shifted?

*

For someone growing into readership in the 1960s in Britain, Enid Blyton was pretty much omnipresent1. She was in the libraries, in the bookshops, and on our bookshelves. The Famous Five, a group of kids (and Timmy the dog), seemed to travel all over the country engaging in plucky adventures that we were encouraged to admire, if not emulate. As astonishing as it may seem, Blyton wrote over 600 books and would sell, at her peak, tens of millions of books a year. To do this, she dedicated her life to writing, a life in which everything else came second, though she apparently carefully nurtured her image as a lover of children.

Then, in a later backlash that played out as the UK cultural environment changed, she was condemned—with justification as far as I can see—not only for snobbery, class prejudice, and xenophobia, but also for racism and gender stereotyping. That’s quite a charge sheet. In some cases, her books have been updated, though this has not been without controversy.

Some of her most famous characters remain national institutions in the UK, however. Especially the Famous Five, who literally became the posterchildren of the Great Western Railway as it tried to encourage Famous Five-style trips among the Boomers and their children or grandchildren through appeals to their cultural nostalgia (see photo above).

I’d missed out on this ebbing and flowing of her reputation, having spent most of the 80s and 90s out of the UK in the years immediately before the internet became widely available. But I became slowly aware of this later, when I moved back to the UK at the start of this century. So Blyton’s changing reputation was probably lurking somewhere behind my inability to connect this time around.

And there was more. Later came the revelation that Blyton had been effectively banned from the BBC for 30 years for being “second rate.” Her writing was widely criticised by others, too, according to Byrne’s monograph: “The literary critics condemned her unchallenging stories, her limited and prosaic use of vocabulary, formulaic plots, and liberal use of exclamation marks in place of dramatic prose.” Ouch. Somewhere in all this, there was a whiff of literary snobbery and perhaps even misogyny—did male authors like the much-loved Roald Dahl receive similar comments, I wonder?

So perhaps all of this was somewhere in my mind as I read on in my fevered feebleness last week. And to be honest, I did feel that Blyton was trying to have fun at the expense of a character who seemed to be hard of hearing and who may have been demonstrating signs of early senility. Was Blyton also ablest? And ageist?

Older now, I winced at the lack of compassion in the way Twiddle is treated in the books. Perhaps that helped to sever the connection to the portal. I didn’t feel a huge sense of loss in terms of the book, I confess, but it seemed like another part of the adjustment I had to make to the loss of my mother just over a year ago.

But anyway, the magic was gone. The roots of The Faraway Tree have been torn out. And Mr Twiddle really had to be put out to pasture. I can’t really bring myself to say that I regret it.

Yet, the time will come again when I have to put down my regular reading and give my brain a little holiday. What should I do then?

Time to find a second-hand copy of The Wind in the Willows, perhaps?

I have taken many of the details about Blyton here from a fascinating monograph by Jenny Byrne at the University of Southampton. It's worth a read if you want to know more about Blyton’s life.

I liked this so much. Deceptively simple and unpretentiously weaving themes of literary life, nostalgia for childhood, illness, time, as well as family connection and continuity. There's more in it, too. A gentle and civilized piece of writing. It did me good in my soul to read it, so thank you.

Ah Enid Blyton. She was truly my favourite author throughout the 1960s, as I was becoming a more proficient reader. It is always difficult to judge an author from another place in time where values and lifestyles were so very different.

I don’t remember ever thinking that her writing was snobbish. I simply read them from the point of view that it was great to have adults ‘out of the way’ in the stories and for the children to have adventures and win every time. These books were written at a time where children were not over-praised and behavioural expectations on us were much higher. We were told things like “Yes you can go out to play in the street and over the park and common, but come in when the street lights come on”. “Don’t answer back”, “just do as you are told”, “do not interrupt adults when they are talking”, “the teacher hit you? what did you do wrong?” …. Few of our families owned cars, so we had to take public transport and find our own way around at a ridiculously young age. Can you imagine giving young children that amount of freedom in this day and age?

I read the Blyton novels from the point of view of already experiencing a lot of unsupervised free time but for me, the stories took freedom to the next level by including adventure and I loved them all and very clearly remember that I couldn’t wait for the break bell at school to go so that I could go and read another chapter. I have rarely enjoyed reading as much as I did at that time in my life. It did not bother me in the slightest when I read of children going to boarding school, having rich parents or housekeepers. I had none of those experiences, but I don’t remember feeling offended by the characters. I just enjoyed the books so much and loved the fact that they were in series so there was always another one to look forward to.

The fact is that language, traditions, morals, belief systems, all change over decades, as does language. When I re-read Enid Blyton to my own children in the 1980s, I upgraded the language and sometimes left out the fact that there was a housekeeper in the stories. My children love them and always begged for ‘one more chapter.’

Lots of older books, such as classical reads like Charles Dickens, Thomas Hardy, the Brontë sisters, are more difficult to read these days as they use language that is more complex than what we would use today.

For me, Enid Blyton books evoke such happy memories of reading for pure enjoyment and escapism and I will be forever grateful to her and other authors of the time, for stirring my imagination, helping me to improve my reading in a safe space, and not being introduced too early to adult concepts of life as well as allowing me to remain a child for that little bit longer.