Adieu! adieu! thy plaintive anthem fades

Past the near meadows, over the still stream,

Up the hill-side; and now 'tis buried deep

In the next valley-glades:

Was it a vision, or a waking dream?

Fled is that music:—Do I wake or sleep?

Ode to a Nightingale, by John Keats

As I grew up and went from weekly baths as a small child to daily showers, I discovered loofahs. Beige, vaguely vegetal, and agreeably caustic on my teenage skin, they felt exotic in a homely kind of way. But I’d never seen the plant they came from.

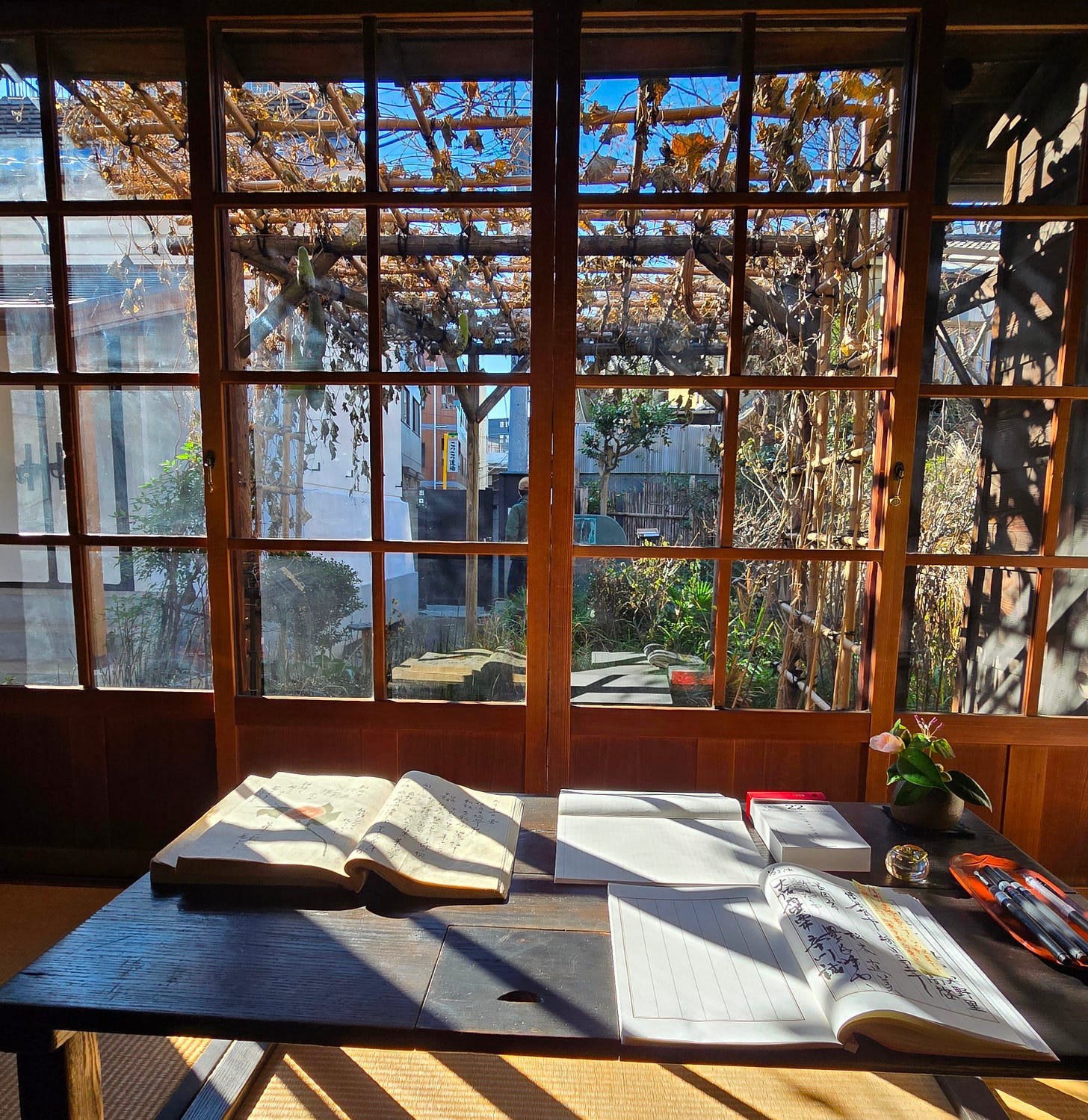

Decades later—just a few days ago in fact—I came face-to-face with a green gourd at the former house of Masaoka Shiki, the Japanese poet whose famous poem about a persimmon I quoted recently. 1 I didn’t know what it was at first. But armed with a mobile phone and its image search capacity, I soon found out that it was a loofah (or luffa) gourd. Luffas are edible when young fruit and the water from them is used in parts of Asia, including Japan; it’s good for the skin and refreshing to the mouth.

Shiki was born in Matsuyama on Shikoku Island but moved to this house in 1894. It was there he spent the last years before his early death in 1902. While drafting my essay on persimmons in Japanese culture, I became fascinated by the lively intelligence of Shiki’s writings as well as his skill and artistry as a poet. He also enjoyed sketching and left a number of fine plant illustrations behind him, which seem to go so well with his poems.

In my earlier essay, I’d mentioned that Shiki, the pen name of Masaoka Noboru, suffered for much of his short life from illness. One of those illnesses was TB, and this accounts for his adopted name. The mouth of the Japanese cuckoo, hototogisu, is so red that it looks like blood when it sings its sorrowful song. At 22, Masaoka Shiki began coughing blood from tuberculosis and decided to adopt the name "Shiki,” which is another way of saying cuckoo in Japanese (hototogisu being the common name). 2

He was already suffering from the first symptoms when he signed up to cover the short-lived First Sino-Japanese War (25 July 1894–17 April 1895) for a Japanese newspaper. The fighting was over before he got to the front to do any reporting, but his health deteriorated during the wartime conditions of hardship he went through while in Manchuria. He convalesced for a time upon his return at the house of Natsume Sosekei before moving to Tokyo for his final years.

Shiki became known not only as a poet skilled at haiku and tanka but also as a critic. Controversially, he placed Buson over Bashō in the pantheon of Japanese haiku writers, and he also lamented the form’s demise. A moderniser who seemed not to relish modernity, Shiki’s complicated relationship with his times is perhaps best summed by his friend Soseki’s own struggles: “Unless we totally discard everything old and adopt the new, it will be difficult to attain equality with Western countries... [yet, to do so would] soon weaken the vital spirit we have inherited from our ancestors [and leave us] cripples.” 3

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to English Republic of Letters to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.