A few weeks ago, I interviewed Richard Walker about his excellent and newly published memoir, “Highlife, & my other lives”.

This week, I’m delighted to feature an extract from the book. I hope you will enjoy reading this passage as much as I did.

First, by way of background, Richard Walker writes:

Attending Oxford University as an undergraduate was an accident for me. There was no particular expectation that I would study there. My father left school at fifteen years old in the mid-1920s during the years of depression, unemployment and the 1926 General Strike in Britain. He was the oldest of eight children from a poor area of Birmingham. He joined the army as a private, which gave him a steady job, food and accommodation.

By the time I was born in the 1950s, product of a late second marriage, he was an older father. I left my boarding school and did my A levels1 in one year, not the standard two. My results were unexpectedly good. The technical college I’d attended encouraged me to apply to Oxford. To everyone’s surprise, I got a place to study English literature at St Peter’s college, all boys/young men then.

I ‘went up’ in October 1971. I spent a lot of my time acting and some smoking marijuana. I couldn’t believe my luck when I learned we were having an audience with WH Auden, who made his reputation as a poet in 1930 when TS Eliot, poetry editor at Faber & Faber, published his first collection and all his subsequent poetry.

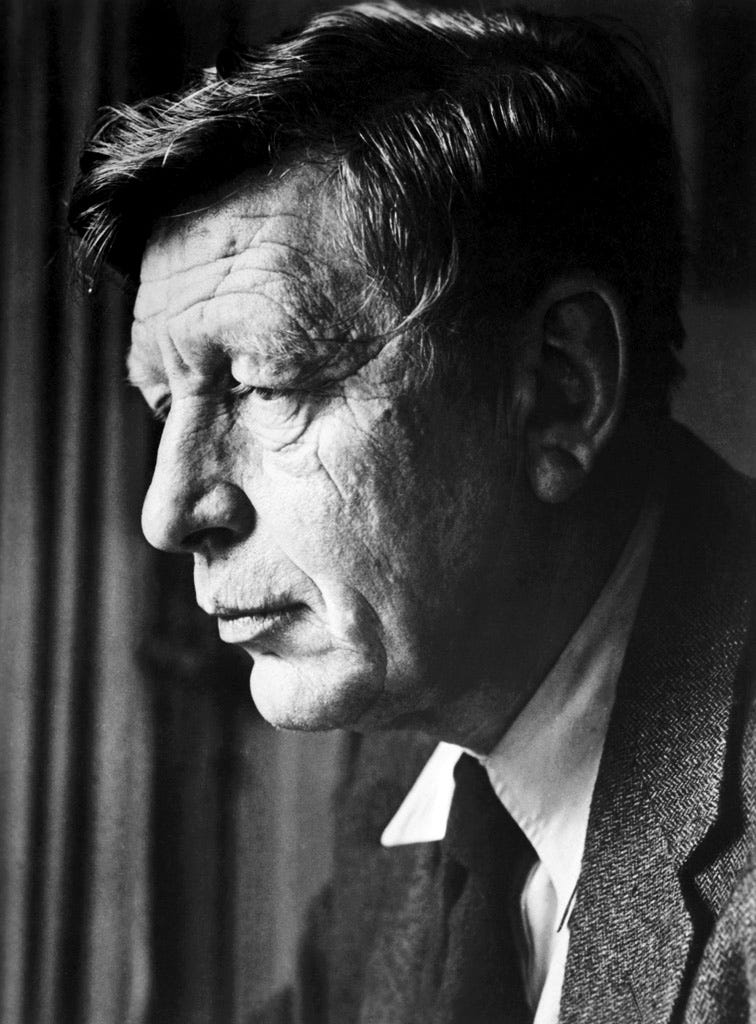

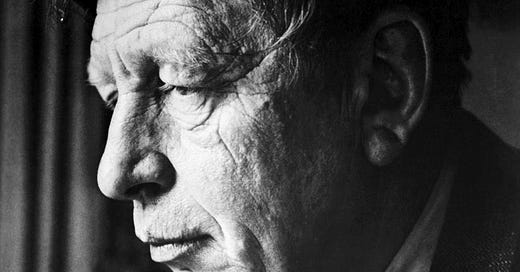

Auden left New York and arrived to live at his old college, Christ Church in the autumn of 1972. He only spent that one winter 1972/73, at Christ Church when the scene which follows took place. He died the following late September 1973 at a hotel in Vienna following a poetry reading. He was supposed to return to Oxford the following day. He was buried at Kirchstetten where he’d bought a small farmhouse in 1958 to spend the summers.

“Francis” in this excerpt is my English tutor, Dr Francis Warner (1937–2021).

Auden at Oxford.

An excerpt from Highlife: & my other lives

In 1972, the grand old man of English poetry, Wystan Hugh Auden, returns from New York to Oxford – to his undergraduate college, Christ Church – with his health failing; and even with his peculiarly high tolerance for domestic chaos, he’s finding life difficult to manage on his own. Grand Auden certainly is in terms of his reputation as a writer and intellectual. He’s the greatest living English poet and I’m excited that we’re going to meet him.

He certainly isn’t old, only sixty-five when he returns to take up residence in a cottage’ – appropriately enough called The Brewhouse – located in a Christ Church canon’s garden.

It’s a late February afternoon when he shuffles into Francis’s study on the third floor of Linton House, the Georgian rectory which is the front entrance of St Peter’s College. There’s no lift to this floor, so Auden has to climb three steep flights of stairs clutching the wooden banister rail. He must have had to gather himself and catch his breath before entering the room accompanied by Francis. We’d been told to be there at 5pm sharp. Auden enters the room at a quarter past five precisely. One fixed point in the chaos of his personal life is an obsession with punctuality. As if clock-watching were an anchor in the stormy sea of his turbulent emotions. His 1969 poem ‘Moon Landing’ comments drily that women wouldn’t have bothered with such ‘a phallic triumph’ and men only made it possible

because we like huddling in gangs and knowing

the exact time.

Like the six other undergraduates in the room, I absorb his battered face, a rare skin condition which has coarsened, thickened and furrowed his skin. But it’s the shambling, shuffling entry which shocks me more, as if we’re suddenly in a hospital or an old folks’ home. This is compounded by his footwear: old-fashioned, ‘grandad slippers’, wool plaid in grey, scuffed, stained and damp.

I wonder whether he’s dragged himself from Christ Church up St Aldate’s, gone left into Queen Street then right along New Inn Hall Street to St Peter’s in those slippers.

Once settled in the large leather armchair he pulls out his packet of Players, a Zippo lighter, and fires up his fag. It’s like watching the opening moments of a drama. His concentration on the task is absolute and we might not be there. We’re the audience whom he’s not yet acknowledged and won’t do so until this opening scene is set to his liking. It’s the slightly weary but consummate professional readying himself for his umpteenth performance, which is what his life seems to him to have become.

Conversing with Auden is like having a conversation with a human-sized lizard turning its head slowly round to meet your gaze. In our discussion about poetry, art, society, science, politics he only allows shades of grey to seep in where he’s still gnawing at an issue himself like a dog at an especially enduring bone.

Otherwise, he’s always decisive and clearly never takes prisoners. We have the discussion under his firm hand of why he changed the line: ‘We must love one another or die,’ to, ‘We must love one another and die.’ And he makes it clear, that his is the last word on it.

Auden’s wonderful poem about Edward Lear seems to me as much about Auden himself as Lear. After all, Auden spent nine summers in Ischia before he and Chester, his American lover, bought the only property Auden ever owned, at Kirchstetten near Vienna. Auden writes about Lear’s demons – he had epilepsy –whist Auden had demons of his own. The poem climaxes in joy and love: ‘And children swarmed to him like settlers.’

At two points Francis provides Auden with a martini. Even his ‘Thank yous’ sound like they might be cloaking another back story, which is, in part, the shimmering in his eyes, and the over-elaborated and mannered way in which he delivers his ‘Thank you, Francis,’ with pursed lips.

I see and hear him shuffling back to Christ Church through the throng of ordinary shoppers – fortifying himself by quietly chanting some Lear:

The Owl and the Pussycat went to sea

In a beautiful pea-green boat.

They took some honey and plenty of money

Wrapped up in a five-pound note.

All in preparation for yet another dinner at Christchurch High Table, where Auden gets disgracefully drunk through the courses and asks an unsuspecting, very distinguished guest whether he, like the Great Poet, finds it tricky alone in his room at night, to piss in the sink.

I’ve experienced the Everest of twentieth-century English poetry, an awesome occasion I treasure still. Though the visible sadness Auden was carrying at the end of his life lingers with me too. He died, like Lear, alone, feeling unloved.

*

Reprinted by kind permission of Richard Walker and the Amaurea Press. All rights reserved. Highlife, & my other lives was published on May 22 2025.

A levels: exams in arts, social sciences or sciences necessary to study at undergraduate level in English, Welsh and Northern Ireland universities.

Thank you for your appreciative comment Maureen.

I feel as if I've read this before--or maybe it was an earlier excerpt. Auden is my beloved poet for all time. And here's one of favorite quotes from the Dyer's Hand that I use in my course online here: "[. . .] What kind of guy inhabits this poem?" and he asks himself this question as well: : "Here is a verbal contraption. How does it work?” That’s the first question Auden asked himself when he read a poem. And it’s a good one. I own the full collection and the biography. More on Auden always welcome., Jeffrey.