What I learnt while dreaming with Don Quixote

A night at the ballet was more instructive than I expected

Last weekend I went to the ballet to see my favourite ballerina dance in “Don Quixote”. And, you’ll be pleased to hear, she was sublime, better than ever.

I then sat down to write the story of the ballerina who had helped me appreciate ballet on a whole new level, due to the sheer beauty of her dancing.

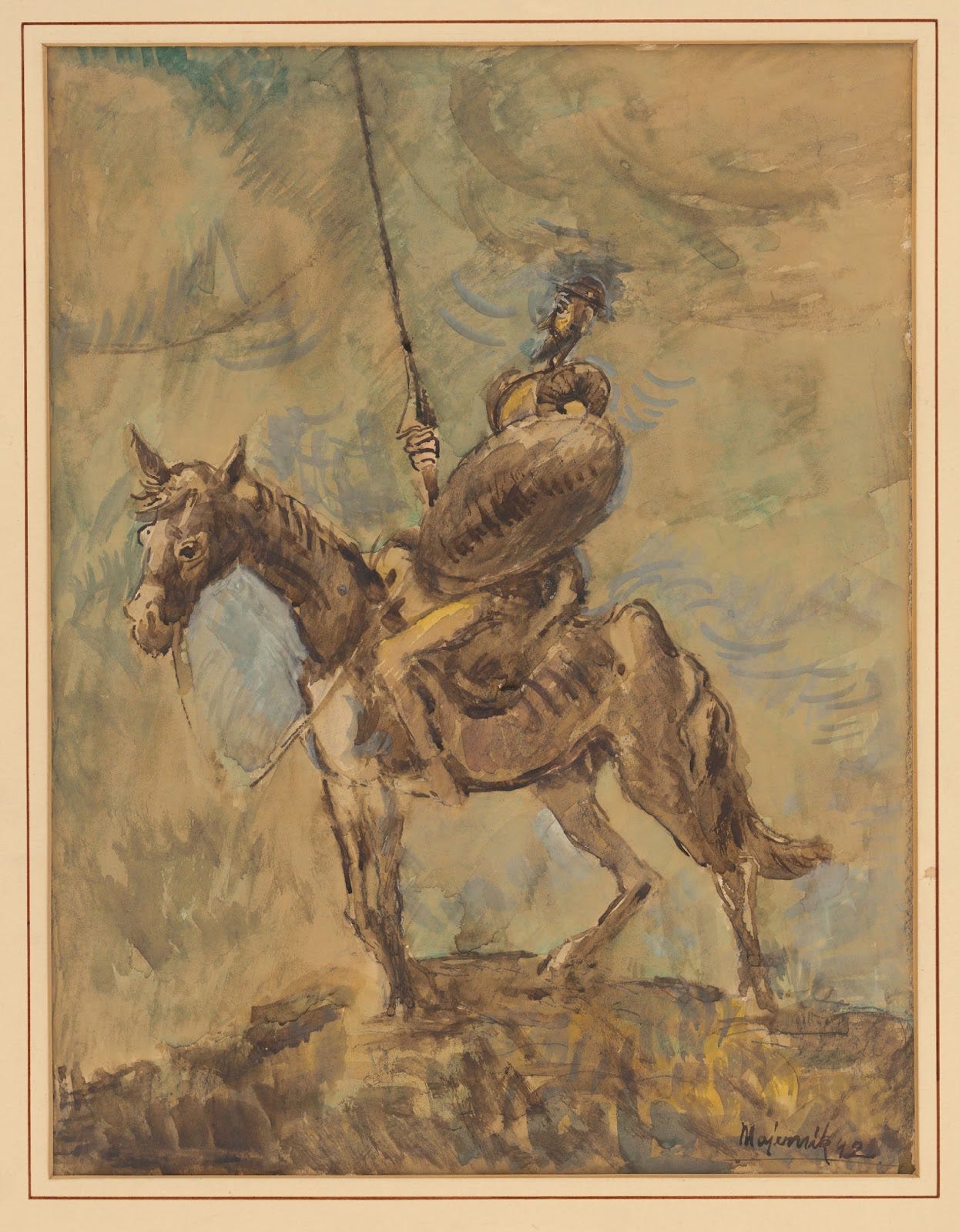

I thought, too, of Don Quixote, one of the most famous heroes of literature, albeit a rather unusual one, beset by fantasies based on his own literary heroes.

And I also thought about art and the pleasure I get from it.

And yet, I ended up not being very sure about whether I had a story to tell or whether I wanted heroes. And there was also something bothering me about my relationship with art. So this piece didn’t turn out as expected. But let’s begin it anyway.

The ballerina

Her name is Yui Yonezawa. She’s possibly the best ballerina you've never heard of. She’s a principal dancer at the Japanese National Ballet, where she has been a member since 2010. As far as I know, the company doesn’t tour and although Yonezawa spent some time at the Ballet San Jose, she doesn’t seem to have developed an international reputation.

I think of her as “Yui-san”. I came across her work when I arrived in Tokyo in 2011. One of the many privileges of my job at that time was to receive invitations to see work at the New National Theatre in Tokyo. I was looking forward to seeing lots of opera, but I wasn’t sure about ballet. Sure, I’d quite enjoyed the occasional performance in the past and was open to going along. But it wasn’t something I was really longing to see a lot more of.

Yui-san changed all that. After seeing her in leading roles a couple of times early on, I realised that there was something that I had been missing in ballet. Yes, I already knew the whole spectacle could be beautiful, the music often lovely, the costumes gorgeous. But there was something in Yui-san’s dancing that I hadn’t noticed in previous dancers.

What was it? A peculiar kind of youthful grace, a subtle joy in the movement, like the brushing of the wind against a blossomed bough in spring. There were levels of meaning in every step, every gesture, every leap, that I simply hadn’t suspected were there before. It was like seeing ballet for the first time. It was enchanting and I was spellbound.

You can watch her dance here and see for yourself:

I have watched a lot of ballet since then. I have seen her equal among ballerinas - who knows, perhaps even better dancers - and yet her performances remain the touchstone for what ballet is for me. I shall always be grateful to her for that.

I even got to meet her a couple of times, giving me the chance to tell her how much her work meant to me. I remember once when I was taken backstage with a visiting dignitary, and we were all huddled together for the obligatory photo. Yui-san was next to me, poised and calm, as if she hadn’t just gone through the incredible exertion of dancing the lead in a full-length ballet (The Sleeping Beauty). I kept a respectful distance.

“A bit closer please”, shouted the Ballet Master, who was taking the photo. Looking at me and the gap I left between me and Yui-san, he added “Don’t worry, you won’t hurt her. She’s a lot stronger than she looks.”

I’ve thought about that moment a few times since. Perhaps it says something about what I admire in ballet, that combination of airy gracefulness with sheer athleticism and strength. Of technique combined with artistry. I also remember a ballet director telling me how he enjoyed working with Japanese dancers because they worked hard at the basics. “Getting the basics right,” he told me “is the basis for everything else in ballet. You have to put the work in.”

While I don’t know enough about the techniques of ballet to judge any technical progression in her work over the years, I have seen a change. It's a growth in confidence, her ability to dominate the stage with her presence. She now has a kind of aura about her. Yet she retains the same humble smile I first saw over 10 years ago.

The book

But as I begin to write, I think, there’s another hero here. It’s “Don Quixote” (1605, 1615), the work which gave its name to the ballet in which I first saw Yui-san dance. Actually, to think that I had first seen her in that ballet means a lot. Cervantes’ great novel goes deep for me. It was actually the second reason for my wanting to learn Spanish, as I didn’t quite get round to mentioning in my first post on language learning.

Unlike Yui-san, I doubt if Cervantes needs any introduction, but if you’re not familiar with his eventful life, which included being wounded at the battle of Lepanto, bureaucratic involvement in the great Spanish Armada, and being captured into slavery, then please check this link.

And if I say I identify with The Knight of the Rueful Countenance,1 it’s not (I think) because of his mental health issues or (I hope) his understated sense of privilege, but because he constantly saw life through the optics of literature and I share the same vice or virtue.

True, my head’s not full of chivalric romances and I don’t tilt at windmills or even own a greyhound. But, usually unbidden, books, fragments of books, phrases from poems, will come to mind in almost any life situation, almost as intrusive thoughts. At times it’s a bit like living in a (rather small) library where all the books are open and thrown on the floor. You don’t know what you will trip over next. It’s a mercy to others that my memory is poor and I am unable to quote passages at length.

A trivial example of how literature intrudes in my life is “The Charge of the Light Brigade”. This is not Tennyson’s poem of 1854. Well, it is, but it’s really his poem as channelled by Virginia Woolf through one of her characters in “To the Lighthouse” (1927). “Someone had blundered...” intones Mr Ramsay at the slightest provocation. Woolf uses the quote brilliantly to create, among other things, a sense of guilt and blame as components of the Ramsay marriage.

Whereas, I use it as a blunt instrument the moment something goes wrong. Tickets for the show forgotten? White bread instead of brown? Car won’t start? “Someone had blundered.” (Invariably me.)

I mentioned in a previous post something about Pablo Neruda’s style of reading his poems as a triumph of the sound of words delivered almost as music. The incantatory opening lines of “Don Quixote” are known to most Spanish speakers, who, when they quote them, will often, in my experience, adopt an unfamiliar cadence and tone, one in keeping with the music of the words themselves. It’s almost as if those words, among the most famous in Spanish, flow like a river of inspiration through the ages and through the language itself. You can hear them here (the first 10 seconds or so).

Returning to the ballet, there is an impressive dream sequence in which Don Quixote imagines glorious adventures, which basically gives the choreographer and designers a good excuse for full-on gorgeous dancing and costumes. It’s over the top, gratuitous and just wonderful.

On the other hand, Don Quixote struggles with real life (I hesitate to mention another parallel with myself here). Or rather, he struggles with negotiating the division between what we are pleased to call real life and fantasy. In a rare narrative moment in the ballet, he witnesses a puppet show, and, taking a dispute on the stage for real, charges at it with violent righteousness. Elsewhere in the ballet, however, Don Quixote generally does little except gesture clumsily with his lance, to the amusement or bemusement of all.

If it is all a little absurd, that’s in keeping with the novel. There is a famous passage (actually a parody of one of the writers Cervantes was making fun of in the novel) which goes something like this: "The reason for the unreason that is done to my reason so weakens my reason, that with reason I complain about your beauty”. “La razón de la sinrazón que a mi razón se hace, de tal manera mi razón enflaquece, que con razón me quejo de la vuestra fermosura”.

It isn’t supposed to make sense.

And the dream sequence isn’t a random element. Dreams were a commonplace of literature going back well before Cervantes’ time, as we know. And if we stay in Spain, at roughly the same time as Cervantes was around, in Calderón de la Barca’s famous work “La Vida es Sueño” (1635), we find this passage:

‘What is life? An illusion,

A shadow, a fiction...’

Dreams can break down our faith in narrative. And while Don Quixote inhabits a kind of dream world, living through a fiction, Calderón de la Barca goes a step further, suggesting that life itself is fiction.

Of course, narrative is rarely the main point in ballet. Before I became a fan, this feature used to annoy me. I would be irritated to see the story in (say) “The Sleeping Beauty” dispatched in short measure. So, in a typical example you’d see:

Prologue

35 minutes

Interval

20 minutes

Act I

30 minutes

Interval

20 minutes

Acts II and III

70 minutes

Act II would be the climax of the story, the prince finding the sleeping beauty and reawakening her (and the other inhabitants of the castle). This is usually over in a few desultory minutes of narrative action, leaving an hour dedicated to the nuptials in Act III, which are basically an excuse for random characters from various folk tales or “exotic” cultures to perform a variety of dances that bear no relation to the ballet’s story at all.

As I say, this used to annoy me. But as I began to appreciate ballet more, the more I enjoyed the pure spectacle of the dance and the less I cared about the story.

Losing my religion

While thinking about my response to Cervantes’ novel or the unmatched grace of Yui-san’s dancing, I find myself reflecting on the importance that art has in my life.

I spend quite a lot of time immersed in some kind of art. Apart from reading poetry or fiction at home, I seek its inspiration at cathedral-like galleries, at vast arenas like the Royal Albert Hall, or at huge libraries that stretch to an almost Borges-like infinity. I relish how painters show transcendent or heroic scenes. And, a country boy at heart, I even listen to music by Vaughan Williams to experience the sensation of a lark ascending in the summer sky. I happily watch a Wim Wenders film to give me insights into mortality and angels.

It all begins to sound like a religion.

But wiser people than me have warned against this:

“If you try, as has been tried so regularly since the Romantics, to atone for the death of God by fashioning art into a political programme, an ersatz theology, a body of mythology or a philosophical anthropology, you will impose on it a social pressure which it isn’t really robust enough to take”.

Atone for the death of God? nothing could be further from my thoughts.

By now, I begin to lose faith all round; in my story of a hero artist, in art as hero. I look for help in an unlikely place:

“Looking for something we can rely on

There's got to be something better out there

Love and compassion, their day is coming

All else are castles built in the air”

No, not Cervantes, nor even Calderón de la Barca. As many of you will know, these words were sung by the late Tina Turner in “Mad Max (1985). And, of course, the famous line and title of the song is: “We Don't Need Another Hero”2.

So, maybe I should see art as just another castle in the air. And I find myself agreeing that I don’t need a hero. Or even a story, for that matter, with its tyranny of beginning, middle and end.

No more Heroes

Waking from my own dream of heroes, where does this leave me?

I realise that in the end, Yui-san is not my Dulcinea. She doesn't need to be anyone’s hero.

What matters in “Don Quixote” is not what Quixote does, but what goes on in his head.

And yes, art can enrich our lives but it does not make us better people or provide lasting transcendence.

While I might agree with George Steiner that “books are the one constant country”, I can’t follow him in adding that “reading them [is] a matter of life and death”. No George, not really, not for me.

So, I conclude I will have no heroes. Not even books.

And my story? That of the youthful Yui-san helping me to find a deeper appreciation of ballet, while old Don Quixote tilted at windmills?

Once again, I look for help, but this time back in my literary comfort zone:

“Thou hast nor youth nor age,

But, as it were, an after-dinner's sleep,

Dreaming on both.”

The beautiful words of Vincentio in “Measure for Measure” make me feel that I can share Don Quixote’s dream. And like him, I watch Yui-san dance, witnessing the simple human grace of movement, magic and imagination.

I decide I can live without heroes. The dance is enough, the words are enough.

The dream is enough.

There are many translations of his soubriquet in Spanish, “el Caballero de la triste figura”. See here for details: https://franklycurious.com/wp/2015/10/03/don-quixote-and-his-sorry-face-translation-comparison/. I like “rueful countenance”, which Smollett used.

"We Don't Need Another Hero (Thunderdome)" is the full title, I believe. The song was written by Terry Britten and Graham Lyle.

oh my goodness, she really is a lovely, lovely dancer. The grace exudes from her very center, which is perhaps what makes her dancing look different. It doesn't feel like an add-on, but rather an outflow. Would love to see her dance in person!

This was fantastic, Jeffery. It is so in-depth and thorough and thought-provoking. I love the ending, you wrap it up so well.

And I absolutely loved this little golden nugget of a description: “to an almost Borges-like infinity.” — wonderful.