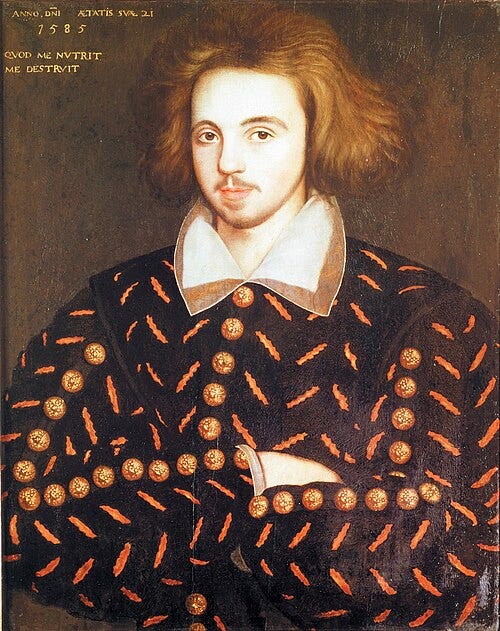

I’d probably never have read Christopher Marlowe’s poem Hero and Leander if I hadn’t followed an old-fashioned English syllabus at university. Marlowe is mostly known these days as a writer of plays, a rival of Shakespeare’s, and, perhaps most of all, for being murdered. 1

I loved the poem, and I still have the book of his poetry and translations I bought all those years ago at university. If the story of Romeo and Juliet brought out some of the best of Shakespeare, the story of Hero and Leander, which has some similarities as a tragic love tale, inspired Marlowe to write some of his most beautiful verse.

Marlowe may or may not have been the poet referred to in Shakespeare’s sonnet 86 when he wrote “the proud full sail of his great verse,” but he’d deserve those words of praise for this work alone.

Here he is writing with a deft touch about the first physical contact between the two lovers:

He started up, she blushed as one ashamed,

Wherewith Leander much more was inflamed.

He touched her hand; in touching it she trembled.

Love deeply grounded, hardly is dissembled.

These lovers parleyed by the touch of hands;

True love is mute, and oft amazed stands.

Marlowe’s readers would have been familiar with the original Greek myth and thus known that the two lovers cannot escape their fate. As Marlowe sums it up:

It lies not in our power to love or hate,

For will in us is overruled by fate.

Love is seen as a force that knows no degrees but comes at once with all its energy or not at all, as in the famous lines:

Where both deliberate, the love is slight:

Who ever loved, that loved not at first sight?

However, the poem’s sumptuous and erotic language cannot disguise an undercurrent of violence. Marlowe uses, for example, an extended military metaphor as Leander tries to seduce Hero:

Yet ever, as he greedily assayed

To touch those dainties, she the harpy played,

And every limb did, as a soldier stout,

Defend the fort, and keep the foeman out.

And even Marlowe’s description of night falling is as powerfully violent as it is forcefully beautiful:

But he the bright day-bearing car prepared

And ran before, as harbinger of light,

And with his flaring beams mocked ugly night,

Till she, o’ercome with anguish, shame, and rage,

Danged down to hell her loathsome carriage.

*

In Romeo and Juliet, the lovers are separated by family allegiances. In Hero and Leander, the lovers are separated by water in the form of the Hellespont (now known as the Dardanelles). This stretch of water had long loomed large in the Greek imagination. The dividing point between Asia and Europe, it was previously the site of the famous crossing by the troops of Xerxes the Great in 480 BCE, an amazing feat of engineering and a pivotal point in the Persian Wars.

One mile wide at its shortest point, it’s a notoriously treacherous waterway, but Leander manages to swim across it often to spend the night with Hero.

At the time I came to read the poem, I was also discovering love for the first time. For the first year, the woman I loved was just a trip by bus and underground away. Later, a four-hour flight out to a small island in the Atlantic separated us.

Unlike Leander, I didn’t need to produce any heroics to bridge the gap but just save up for an airfare. I didn’t need to swim the “rising billows” of the “narrow toiling Hellepont” but simply get myself to Stansted Airport to catch a cheap flight to Tenerife.

The heroically determined Leander had to suffer being pulled down by the dangerous waters to meet his love:

Leander strived; the waves about him wound,

And pulled him to the bottom, where the ground

Was strewed with pearl, and in low coral groves

Sweet singing mermaids sported with their loves.

All I needed to do was sit in my seat and be jostled by turbulence over the ocean for a few hours in the charge of the unsinging cabin crew.

But at least I was travelling, to use Marlowe’s words:

Much like a globe ...

By which love sails to regions full of bliss.

And many times since, at the end of long journeys around the globe that he could barely have imagined, I have experienced the feeling that Marlowe captured so well when describing Leander’s return home after seeing Hero:

Home when he came, he seemed not to be there,

But, like exiled air thrust from his sphere,

Set in a foreign place.

*

Caught up in my own story as well as the sheer romance and beauty of Marlowe’s poem, I never imagined that one day I’d see the Hellespont (Dardanelles) for myself.

But in 2007 I found myself working in Turkey. And my duties took me to the town of Çanakkale on the Asian shore of the Dardanelles, to visit British artist Mark Wallinger’s ‘Sinema Amnesia’, part of an EU-funded arts project that my employer, the British Council, was managing.2

And viewing the swirling waters near this artwork, I realised that we weren’t far from where the ferocious 1915 battle for Gallipoli (Gelibolu Muharebesi in Turkish) had taken place. This bitter campaign between Ottoman and Allied forces led to the death of over 100,000 soldiers.

One of those killed was Jean Verdenal, a friend of the poet TS Eliot, who later dedicated his Poems 1909-1925 to his friend:

To Jean Verdenal

1889-1915

mort aux Dardanelles

Eliot also used an epigraph from Dante’s Divine Comedy, words spoken by the Roman poet Statius and addressed to his revered predecessor, Virgil:

Or puoi la quantitate

Comprender dell' amor ch'a te mi scalda,

Quando dismento nostra vanitate,

Trattando l'ombre come cosa salda.

(You may see the measure of the love which

warms me towards you

When I forget our insubstantiality

Treating shades as if they were solid and real)

(Translation by John Peter)

Some have also suggested that Verdenal’s death influenced Eliot’s most famous poem, The Waste Land (1922), and that he was the inspiration for Phlebas the Phoenician (“a fortnight dead”) in the Death By Water section.

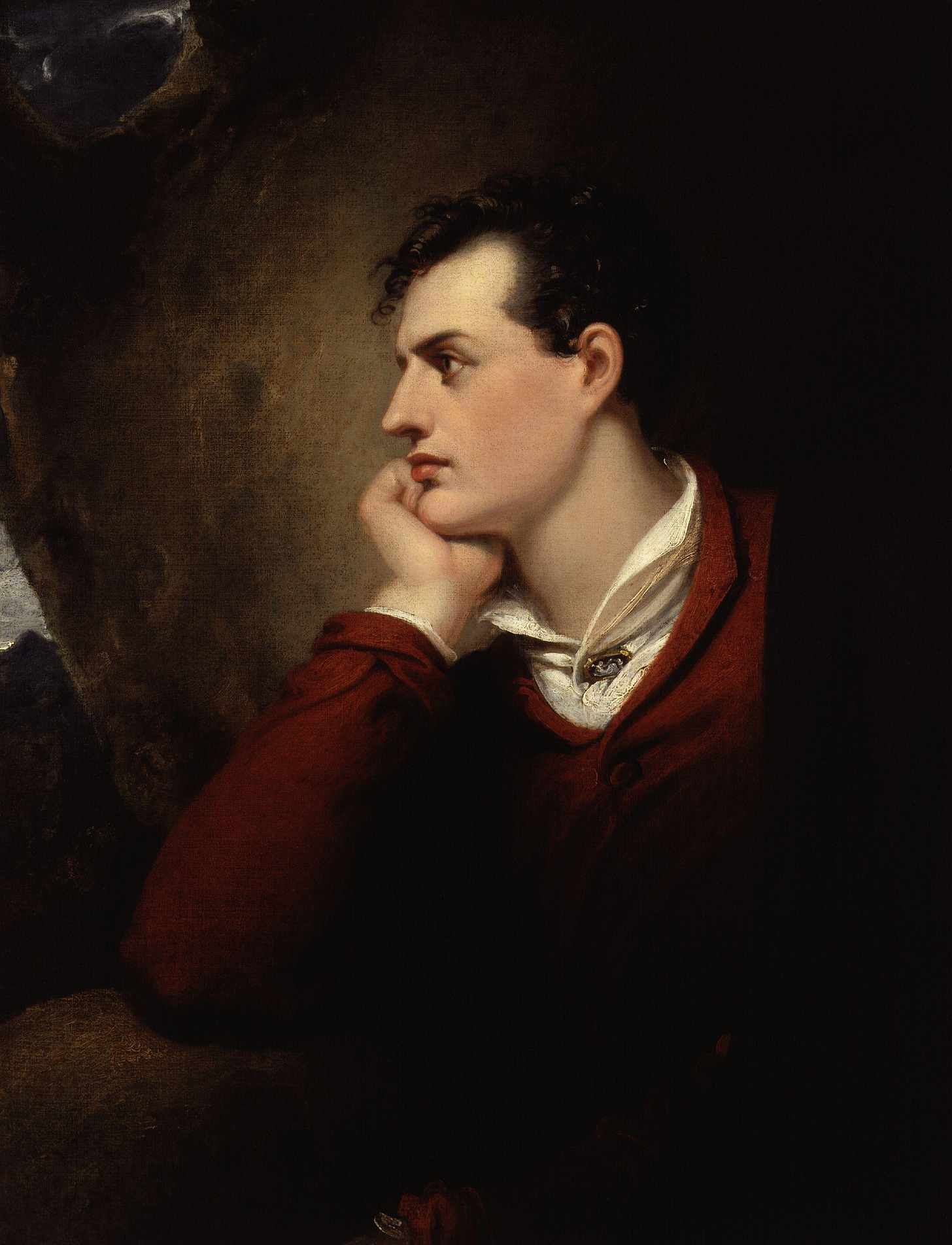

But as I stood by those waters, I also recalled that Leander’s feat of swimming the Hellespont had caught the imagination of another poet, Lord Byron. On 3 May, 1810, he swam it himself in emulation of Leander’s epic journey and was very proud of the fact: “I plume myself on this achievement more than I could possibly do on any kind of glory, political, poetical, or rhetorical.”

Byron’s short poem about the feat is playful rather than full of vainglory, however:

For me, degenerate modern wretch,

Though in the genial month of May,

My dripping limbs I faintly stretch,

And think I’ve done a feat today. 3

*

Two years later, another adventurer came along, following in Byron’s footsteps (and his wake) around the Aegean: the actor Rupert Everett, who was making a documentary called The Scandalous Adventures of Lord Byron.

Keen to emulate Byron (and Leander), Everett bravely attempted to swim the Hellespont but had to give up; it’s now a busy shipping lane, with large cargo ships constantly ploughing through the straits, a real hazard to swimmers.

But the actor attempted less arduous feats, too. He attended a reception hosted by the consul general for a group of visiting ministers and officials. They were attending a conference regarding Turkey’s relationship with the EU. This was held in Pera House, which was constructed as the first purpose-built British embassy starting in 1844— a successor to the building that Byron had visited during his own visit to what was then called Constantinople. It’s a grand building, overlooking the waters of the Golden Horn, described to me, though, by one previous inhabitant as “sub-optimal for modern diplomacy”.

However, Pera House was a superb venue for this reception, and you can watch Everett attending it on this YouTube video. 4

*

Killed on 30 May 1593, Marlowe left Hero and Leander incomplete. The poem was finished by George Chapman, now most famous as a translator of the Iliad and the Odyssey (Odysseus, or Ulysses, also sailed through the Hellespont).

Like Marlowe, the fictional Leander met an early death. In his case, he drowned, “bruised and torn” – to use Chapman’s words – when the light from the lighthouse that used to guide him blew out on a stormy night.

O sweet Leander, thy large worth I hide

in a short grave

exclaims Chapman, before dispatching Hero with an even shorter grave of words:

And with Leander’s name she breathed her last.

Byron survived his swim across the Hellespont (despite catching “ague”), but, years later, he would succumb to fever while supporting the fight for Greek independence from the Ottoman Empire in 1824.

*

The last time I left my current “foreign place” and travelled across the globe to London, I took a fast train down to the city of Canterbury. Leaving the station, I crossed the river (fortunately, there’s a bridge) and made my way to the city centre. There I visited the cathedral, the centre of the worldwide Anglican communion. I also found it to be, to a remarkable degree, a museum celebrating England’s history (Henry IV is buried there) and above all commemorating its wars. A striking number of individual and collective war memorials are on display there.

In this most official of English buildings, the repository of so much pageantry and pomp, it came almost as a surprise to recall that Marlowe, called by some a heretic or “magician”, was born in Canterbury. In the city, though, there’s a theatre and a moment in his honour. The other visible sign of him was the hollowed-out tower of the church where he was christened in 1564.

Apparently, Marlowe attended the King’s School, which is very near the cathedral, a building he would have known well.

According to one account, “Elizabethan schoolboys spent much of their time being told what they had to believe without ever being given intellectual reasons for doing so.”

At the same time, they were let loose on the pagan classics, which included Ovid, Catullus and, of course, Virgil. Perhaps it’s little wonder that Marlowe (who would be accused of atheism shortly before his death) seemed to relish the pagan theology around Hero along with her beauty:

So lovely fair was Hero, Venus’ nun,

As Nature wept, thinking she was undone.

As I stood amid the almost oppressive orthodoxy and gloom of the cathedral, it was difficult to envisage Marlowe’s deviation from dour Elizabethan religious norms. It was much easier, astonishingly, in the seat of the Archbishop of Canterbury, to imagine Marlowe’s brutal death, which the violence in his unfinished poem seems to prefigure.

Because the cathedral is, of course, famous as the site of the murder of Thomas Becket, Archbishop of Canterbury, in 1170. He was killed by four knights keen to act on the intemperate words of their monarch, Henry II.

The king had apparently said, with reference to Becket, “What miserable drones and traitors have I nourished and brought up in my household, who let their lord be treated with such shameful contempt by a low-born cleric?” The knights (along with a cleric) took this as a regal command.

TS Eliot, long after his friend Verdenal’s untimely death, wrote a play about Becket’s martyrdom. In Murder in the Cathedral (1935), written in the long run-up to the Second World War, the doomed Archbishop Becket muses at one point,

...from generation to generation

The same things happen again and again.

Men learn little from others' experience.

As I stood in the massive cathedral’s transept, these words seemed to express the crisscrossing patterns of history and legend ricocheting in my mind while I thought of Marlowe’s last poem and the turbulent waters of the Hellespont.

At that moment, surrounded by the stone tombs of kings and bishops and countless memorials to those fallen in war, I began to wonder if the dead weren’t beginning to whisper their own versions of history to me.

I even imagined I could hear Marlowe parsing the Latin of Virgil or Ovid while huddled over his desk at school in Canterbury, just a few hundred yards from where I stood. The vast building seemed to reverberate with the voices of the past.

But I shook my head at these unheard sounds and at my folly. Because I felt the danger of drifting too far into the shadows of antiquity, of becoming a captive to the unrelenting ghosts of history.

That’s what happened, after all, to the poet Statius in Dante’s Divine Comedy: about to leave purgatory, he declared he’d be willing to stay there a year longer, in defiance of the rules of the place, if only he could have lived in the time of his revered Virgil.

And I began to fear that if I stayed too long listening to those murmurs in the towering stone building, I could grow too warmly attached to them and that, like Statius, I might find myself “treating shades as if they were solid and real”.

Or killed in an act of self-defence by someone he attacked – many versions exist.

As the Financial Times described the work, “Entitled ‘Ulysses’… it replays exactly what has happened in the previous 24 hours on the straits outside, from the eternally frozen soldier to the boats gliding by… Wallinger distils the straits’ epic history into an eloquently simple act of memory that is also a monument to the here and now.”

You can see Everett’s attempted crossing of the Hellespont from 29.00 to 32:50 in the video and the reception at Pera House from 23:50 to 28.35 (where Everett tries to scandalise the guests – with some success). It fell to me that evening to introduce the actor to the Dutch foreign minister. I appear fleetingly in the video.

It's such a treat to read your posts. There is so much going on in this one, your loves in college, the woman and Marlowe, mighty swims by Leander, Byron and a try by Rupert Everett. You effortlessly weave in Eliot, Gallipoli, Beckett and Canterbury and close with an almost ghosty storyline. I loved it.

I've never read Marlowe's Hero and Leander or visited Canterbury. I must make the effort to do both!