Dear Reader

As I am on my summer break until the end of June, I am re-posting essays from September 2023, the month I started writing on Substack. As the number of subscribers and followers to English Republic of Letters numbered at most a few dozen that month (this essay, for example, was originally sent to 51 subscribers), most of you won’t have received these postings the first time around. I hope the hardy stalwarts who have been with me since then, and to whom I owe a special debt of gratitude for your support since those early days, will forgive the repetition.

Your comments are very welcome, as always.

It was the 1980s, I was sitting on a beach, the sand was warm, the sea sparkling and inviting and the sky a delicate hue of blue. I was reading Pablo Neruda’s Cien Sonetos de Amor (One Hundred Love Sonnets, 1959), set on the beach in Isla Negra, a coastal town in Chile, which sounded idyllic in the poet’s evocation.

The beach I was on seemed rather unexotic by comparison. The town of Paignton, Devon, in south-west England, is hardly a fancy town, though it is set on a picturesque bay. It was—and still is, in many ways—quite a gritty kind of place, with its fair share of the usual social problems besetting English seaside towns and decidedly lacking glamour. Even the birdlife lacked class; shrill herring gulls swooped on tourists to steal ice cream, and ragged crows foraged for scraps along the promenade. Not how I imagined Neruda’s Isla Negra at all.

I really never thought that within a few years I’d be sitting on a beach in South America reading the same poems and enjoying the astonishing flight of pelicans and frigate birds along the shore. I was in Ecuador, not Chile, but it was the Pacific that stretched out in front of me and it felt almost like a homecoming. The roar of the surf and the sands stretching for miles, littered with hermit crabs scratching their way from the smooth surfaces, were wonderful to me. I have since found out that Neruda was a very keen birder. He would surely have enjoyed watching, just as much as I, the smooth progress of the brown pelicans (or its larger Peruvian cousin) in ever-changing formations gliding right above the surf.

This month, I have been thinking about Neruda and Chile (a country I still haven’t visited, much to my regret). 50 years ago, a brutal military coup brought down Salvador Allende’s democratically elected government and ushered in many years of vicious repression. For many people, including myself, it remains a dark day in the history of democracy. And surely no one would disagree that the events of September 1973 in Santiago continue to reverberate around the world.

Closely associated with the regime, Pablo Neruda died just a few days later, on 23 September 1973. Mystery surrounds the exact cause of his death, though we know he was being treated for cancer. It’s possible that he was poisoned. But it seems unlikely that we will ever know for sure.

Neruda’s legacy is complex and controversial. But for me, he was, for years, the soaring voice of poetry, the embodiment of poet and poetry as part of public life and as a defender of a Latin American heritage that he explored with so much passion in his ‘Canto General’ (1950).

And when I say “voice” I mean that literally, as well as metaphorically. Early on in my exploration of his poetry, I found a recording of him reading his poem ‘Alturas de Macchu Picchu’ and I was transported by the opening lines:

Del aire al aire, como una red vacía,

iba yo entre las calles y la atmósfera, llegando y despidiendo.

(a literal translation might be: “From air to air, like an empty net/I went through the streets and the atmosphere, arriving and departing”).

You could say his voice was slightly histrionic for many Anglo Saxon tastes but it has a lilt, a rhythm, a fluent musical quality that is hard to resist - for me, at least. And it passes every test about poetry needing to impact your senses before your mind.

I’d encourage you to listen to this recording:

Years later, when I discovered that declaiming these opening lines (and then improvising the rest, as required) was a sure way to make my teenage sons cringe, there was no holding me back. In any case, Neruda’s voice took up residence in a corner of my brain and never left it.

Discovering Neruda’s poetry back in my Devon days was the beginning of a lifelong preference for reading poetry in the open air. Whether it’s been ‘The Waste Land’ or ‘Essay on Man’ on the beach, Ted Hughes or Robert Browning in the park, Louise Glück or Lucille Clifton on a balcony looking out to Victoria Harbour in Hong Kong, some of my best memories of reading poetry have been with the sun and wind (or rain) on my face.

Perhaps poetry is an outdoor thing for me because it is more immediate than other forms of writing, more sensual, more intense and so is more at home in close proximity to the stream of sensations that that we feel while sitting on the sands or with our backs on a cool lawn? Or maybe it’s because my first memories of enjoying poetry as a boy were when I was living on a farm? I don’t know.

But certainly, when I used to take summer holidays from my busy office job, I would always make sure I had with me a new book of poems - ideally a big fat “Collected” - which was always my idea of summer reading.

I don't have summer holidays as such any more and for practical reasons almost every book I buy has to be digital, but I still have my old volumes of verse, the pages bleached from the sun or stained with suntan lotion to remind me of those times.

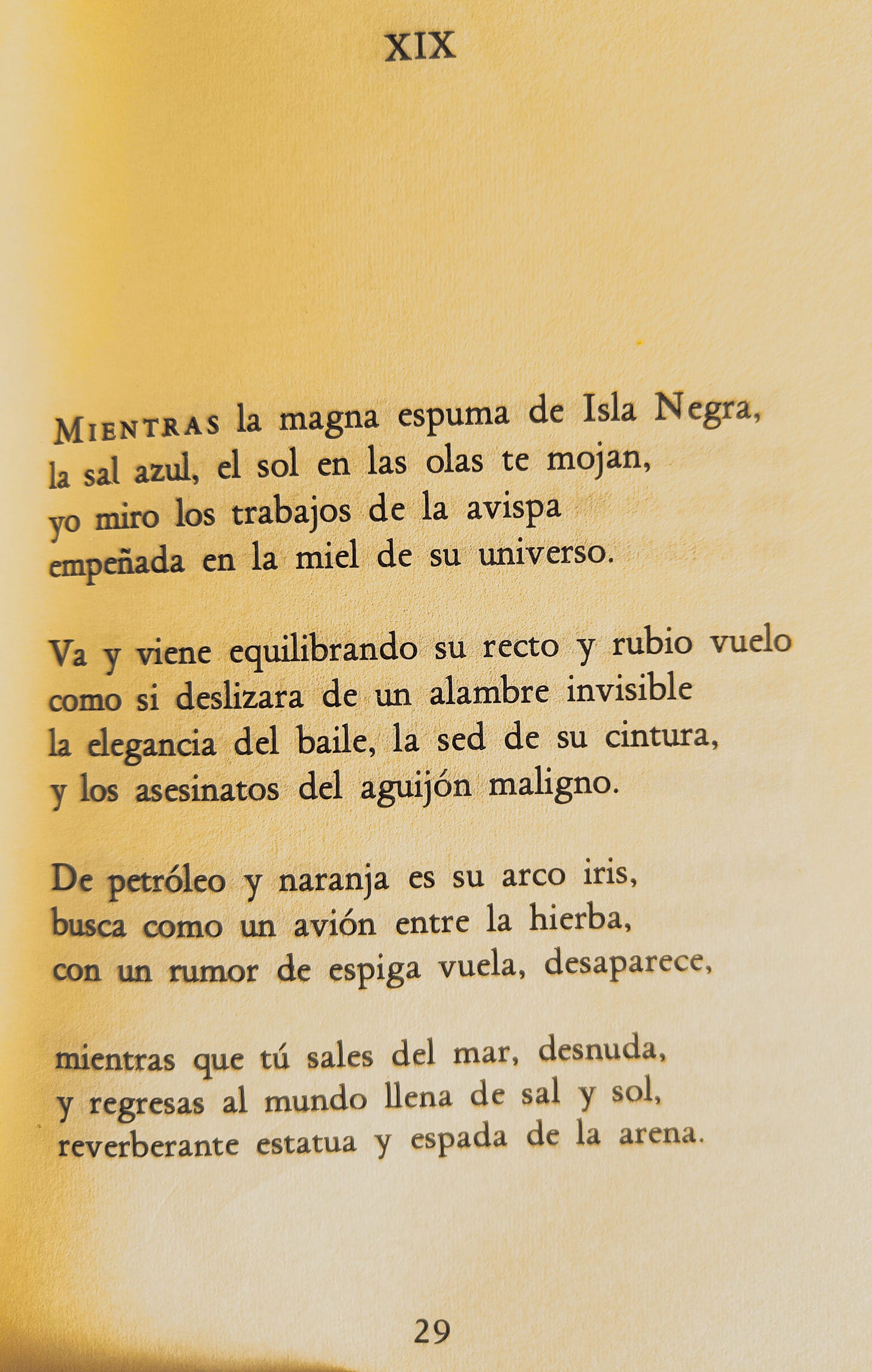

And one of those books, somewhat the worse for wear, contains poem XIX from Neruda’s “Cien Sonetos de Amor”). Every time I read this poem I think back to Paignton, to the Pacific, to the pelicans and, of course, to Neruda on the beach:

Sonnet XIX1

While the great surf of Isla Negra,

the blue salt, the sun on the waves soak you,

I watch the labouring wasp

intent upon its honey universe.

It comes and goes, balancing its straight and yellow flight

as if sliding from an invisible wire

the elegance of dance, the thirst of its waist,

and the murders of the malicious sting.

Its rainbow is crude oil and orange,

as it searches like a plane among the grass,

with a prickly murmur it flies, disappears,

while you come out of the sea, naked,

and return to the world full of salt and sun,

an echoing statue and sword of the sand.

The translation is my own

Note: The image of Neruda above was generated using AI. Since then, I’ve stopped using AI-generated images for my newsletter.

How have I never read poetry outdoors? Thank you for the update to my summer plans!

Have you read Borges ? I had a weighty book with samples of his work. Unusual is almost TOO MILD to describe it.