The moon wanes and the wild goose flies high

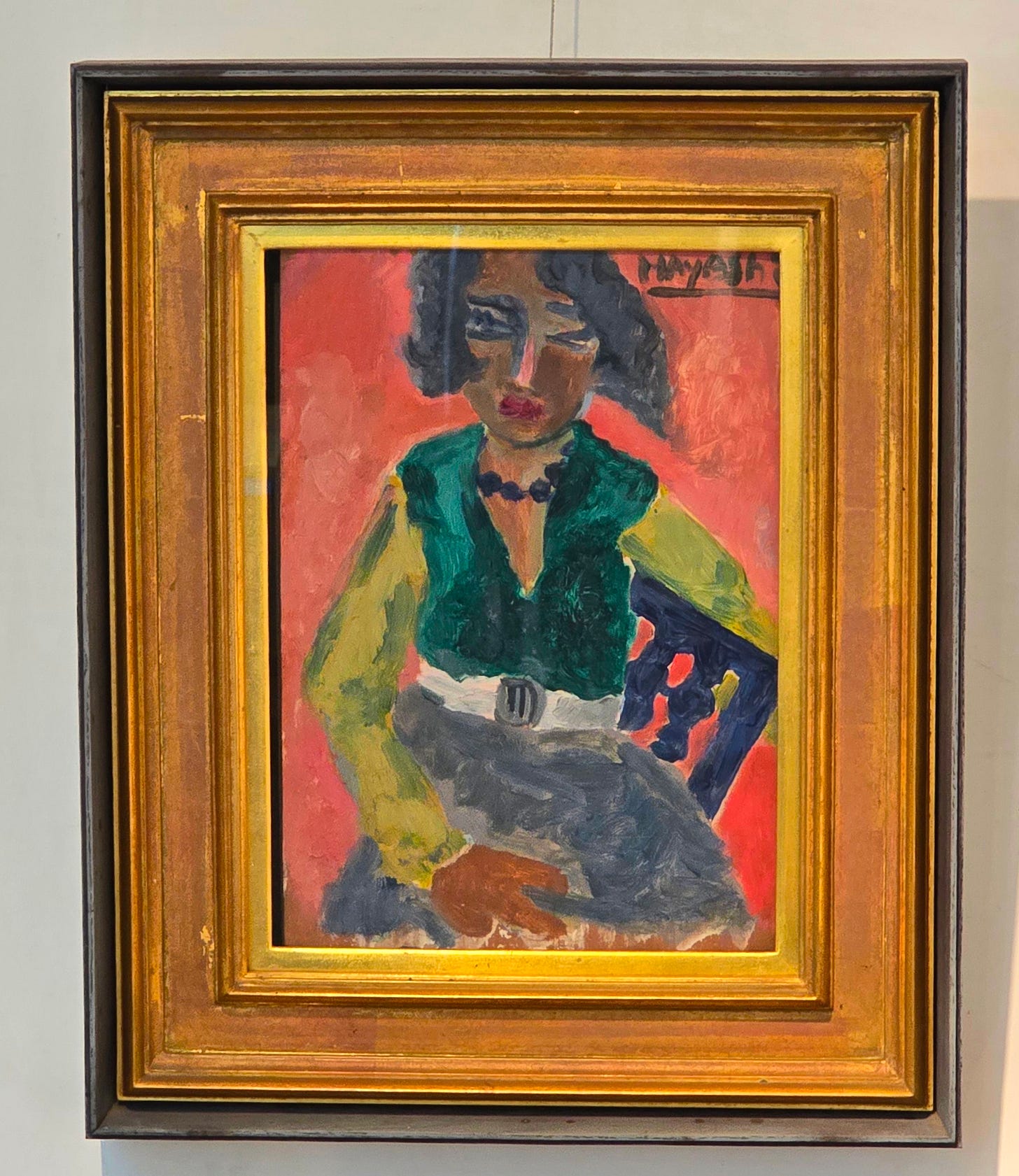

The remarkable life and work of Japanese writer Fumiko Hayashi

Arriving at the former house of Japanese writer Fumiko Hayashi (1903-1951) this winter, the first thing I noticed was the tall bamboo culms (stems) that dominate the entrance. Hayashi had enthusiastically planted a lot of bamboo, a plant she loved. It had apparently once covered much of the garden. Thanks to her, in the typically brilliant winter sunshine of Tokyo, I was able to enjoy the komorebi (木漏れ日, the Japanese word for the dappled sunlight filtering through the leaves of trees), which for me has a special quality seen through a bamboo grove.

Hayashi was proud of her garden, proud of the house she’d designed, inspired by residences she’d seen in Kyoto. It’s now a museum in her honour. The garden was a main feature, but unlike the poet Shiki, whose house I’d visited earlier in the year, she didn’t gaze at it much from her study – apparently her sight wasn’t very good, and she even had to press herself up against the paper to see what she was writing.

However, the room seemed cosier than that of Soseki and well equipped with a huge teapot. And while Shiki had his sister to look after him, Hayashi wouldn’t let anyone in her study, which she insisted on cleaning herself. I doubt if Shiki ever did a lot of housework.

The quiet calm of the house made me think of the one that features in her late story, Late Chrysanthemum (1948), in which a geisha’s former lover, Tabe, coarsened by war and the realities of post-war life in Tokyo, visits the geisha, Kin, to ask her for a loan:

Tabe was mystified by the way Kin lived, by the way the cruel world outside had, it appeared, left life in this house completely untouched.

*

Like Soseki, Hayashi had a difficult childhood. Hayashi faced rejection from her father, who refused to recognise her legitimacy, and then took a geisha mistress, causing Hayashi and her mother to leave home. Her mother then remarried, this time to a much younger man, and together they eked out a living as peddlers in the coal-mining region of northern Kyushu.

After finishing school, Hayashi relocated to Tokyo, where she supported herself working as a maid, a factory worker, and a café waitress while writing and seeking a literary career. Hayashi’s poverty in early life also sets her aside from Soseki, and her work, though well-known in Japan, is not, as far as I know, part of the school curriculum in the way his is.

Hayashi’s most famous work is Diary of a Vagabond (Hōrōki), a semi-autobiographical novel which was published in 1930. This work and some of her other stories, such as The Accordion and the Fish Town (1931), invite comparison with the George Orwell of Down and Out in Paris and London (1933) and The Road to Wigan Pier (1937). But unlike the Eton-educated Orwell, Hayashi had no privilege behind her. And nor did she turn to politics as a main theme, though it’s certainly present in her writing.

There is instead a definite lyricism in her work, and I find the light and shade combine beautifully in her writing, rather like a literary form of komorebi. For instance, in Diary of a Vagabond, the narrator is initially scathing about the conditions of the factory she’s working in.

Morning to night we daubed on primary colours, wriggling like earthworms in a warped factory hidden away from the sun. Slowly but surely, without respite, they squeezed from us long hours, youth, and health. Pity overwhelmed me whenever I looked at the faces of all the young women.

She then continues, however,

But wait. Just think of how the kewpie dolls and butterfly barrettes we made festively decorated the heads of poor children. It was probably all right to smile a little bit beneath that window. 1

The compassion of the writing shines through here, as well as a determination to see the brighter side of life, despite the darkness that surrounded her. Perhaps this was a survival strategy that drove her on through the hard times she had to endure.

I wrote in relation to Shiki and his friend Soseki about their troubled relationship with modernity. The critic Joan Ericson has written of Hayashi in terms of the impact of modernity too, but for her it’s not just a spiritual issue but a physical, even visceral one:

In my view the originality and power of her work are rooted in...the clarity and immediacy with which she was able to convey the humanity of those occupying the underside of Japanese society. She captured the resilience of people who existed on the margin and the ever-resurgent tenacity of those for whom modernity was an unrelenting catastrophe. 2

A moving example of this solidarity is from Diary of a Vagabond when the narrator describes the solidarity she finds in the women who, like her, are working on the fringes of society:

Despite its location at the exit of the red-light district, this shop was surprisingly quiet. I was able to become friends with the other waitresses right away. No matter how ill-natured or hard-boiled they might be at first, no matter how guarded and without the least inclination to be friendly or altruistic, at some point women working in a place like this open up to reveal their true selves. They suddenly lower this guard, and, as if they'd been fast friends for years, they're closer than sisters. When the customers had gone, we would often curl up like snails in a circle and talk. 3

An element of Hayashi and her narrators’ resilience is their love of poetry; not only poems but the magic and the wonder of the everyday. Diary of a Vagabond is full of quotes of poems from her or other writers, and amid the grimness of daily life, she’s determined to see the beauty in it too.

Hayashi will switch from realism to a kind of poetic lyricism in her descriptions of the world she observes.

In my two-mat room the earthen pot, the rice bowls, the cardboard rice bin, and the wicker clothes basket, together with the small desk all stood firm, as if my lifetime debt. The morning sun sparkled through the transom and streamed above my futon laid out diagonally, dividing the room. The dust danced in stripes over my head. Where exactly blew the wind of revolution? You Japanese radicals certainly knew many clever words. I wondered exactly what kind of fairy tales the socialists were inventing. Exactly how much longer did we have to separate newborn babies by class, babies puffier than brown rice buns, by choosing for them a silk or a cotton diaper? 4

The narrator’s emphasis on self-reliance and independence – from employers, from politics, from family and especially from men – extended even to religion. In one striking outburst in Diary of a Vagabond she says,

I could hear a faraway Salvation Army brass band playing, "Come to me, all ye who believe, to your Savior." What was this "ye who believe" stuff? If you couldn't believe in yourself, you couldn't believe in Jesus or Buddha. Poor people didn't have time to believe. What was this religion that they even advertised with a brass band? They didn't have to worry about making ends meet. So it was "Come to me, all ye who believe," huh? I'd had enough of such dour music. I wanted a spring song. I'd rather be retching my guts out, crushed by a nobleman's car on the beautiful streets of the Ginza, than listening to this. 5

*

Hayashi’s Diary of a Vagabond sold very well and was made into a film in 1935. The book’s success made her money and eventually allowed her to buy the plot of land in Tokyo where she’d build the lovely house she spent her last few years in. And the films made from her work and the success of a long-running play about her early life have helped to keep her name well known in Japan.

But she is relatively little known outside Japan. Her works are not readily available in English. We’re indebted to Joan Ericson for including Diary of a Vagabond in her excellent critical study Be a Woman. But it would be wonderful to see a collected works appear in English.

After the war, with mournful elegance, Hayashi captured the state of the burnt-down Japanese capital in her story Downfall (1947):

The most beautiful lights that civilisation had left behind flickered here and there in the devastated city. From somewhere came the sound of a steam train. The toot of the train’s whistle rang out mournfully over a scorched field and out towards the night sky. It was silent all around, except for the occasional passing car or train, as if declaring that Tokyo’s nights would remain desolate for all eternity. 6

*

Wandering around the grounds of her garden this winter, I imagined a writer who, despite the destruction she’d lived through, looked back with justifiable pride at how her work had brought her financial security and a reputation as one of Japan’s leading writers.

But having survived such hardships and the war, Hayashi did not live into old age to enjoy her hard-won tranquillity, dying of heart disease in 1951. Her friend, the Nobel laureate for literature Yasunari Kawabata, spoke at her funeral.

I don't have a record of what Kawabata said about her on that occasion. But from her own writings, the words that I think best sum up her remarkable life are the beautiful, buoyant words from The Accordion and the Fish Town as she considers the light and shades of life:

The moon wanes and the wild goose flies high, but no matter how miserable things get, as long as my body is in one piece there must be a way to get through it all. 7

Ericson, J. E. (1997). Be a Woman: Hayashi Fumiko and Modern Japanese Women's Literature. United States: University of Hawaii Press, pages 142-3.

All my quotes from Diary of a Vagabond are taken from this invaluable book, which includes Ericson’s translation of the novel.

Ericson, page 58.

Ericson, Diary of a Vagabond, pages 179-80.

Ericson, Diary of a Vagabond, page 143.

Ericson, Diary of a Vagabond, page 141.

Downfall and Other Stories (Hayashi Fumiko Book 1), page 49. Translated by J.D. Wisgo. Kindle Edition.

The Accordion and the Fish Town (Hayashi Fumiko Book 3), page 42. Arigatai Books. Kindle Edition.

Wonderful essay, Jeffrey. Very moving. I’m reminded of the brilliant Tillie Olsen, especially of her famous story “I Stand Here Ironing.” What an extraordinary life. To explore one’s past without bitterness or shame is remarkable; to hold it with tenderness is a gift. Thank you for bringing us one more writer who deserves to be known beyond the boundaries of language and geography.

Always fascinating to read about creative people. I can't believe how there was time to write and being a maid and all the difficult jobs she had to do. What a strong and powerful lady. I've never heard of her before this. Thank you for sharing and her writing is very poetic.